It can get tricky discussing the new book by an older, well-deserved writer. Should you take a critical look at it like all other new releases? Didn’t that seem inappropriate, somehow embarrassing? On the other hand, if you didn’t do it, you would give the impression that you no longer take the author fully just because he has exceeded a certain time limit. Then respect for age turned into condescension. Now the philosophy historian Kurt Flasch, who has written countless learned and extremely stimulating works on older and more recent intellectual history, has presented a new publication. He is 91 years old. Fortunately, however, everything is very simple here: it is simply an interesting, thought-provoking book full of surprises.

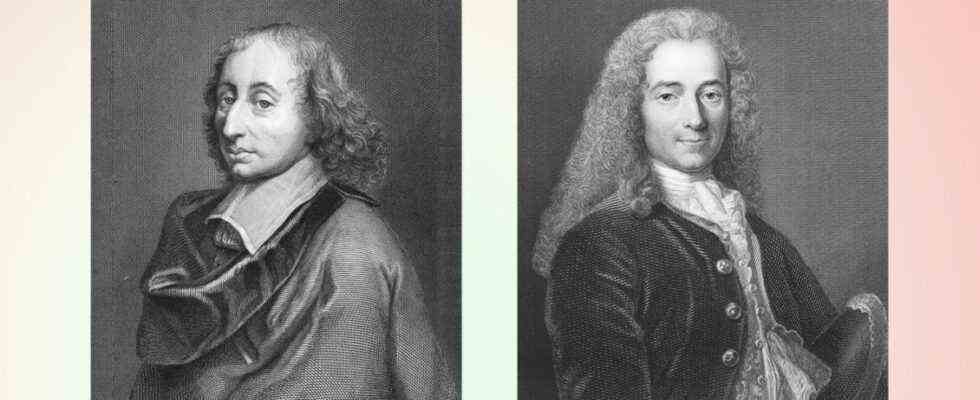

Flasch takes on a classic theme and gives it an original twist. He wants to examine the relationship between Christianity and the Enlightenment, more precisely to find out whether an Enlightenment of Christianity is possible. To do this, he chooses an epoch-making constellation and analyzes a fascinating source that is hardly known in this country: over 200 notes that Voltaire, who lived from 1694 to 1778, made of the 800 papers in which Blaise Pascal, who lived from 1623 to 1662 lived, had lost his understanding of the Christian religion.

Contrary to what one might have suspected, these are not mockery, but documents of a very serious discussion of a theology which the Enlightenment tried to overcome because he saw himself as religious, albeit in a different way. For Voltaire, the struggle with Pascal was the medium of his search for a modern, life-serving faith. By staging the literary dialogue between these two, Flasch is also pursuing a vital question of his own. As he writes in the foreword, after the Second World War, which hit his family hard, he had a phase of Pascal enthusiasm. In the years of need, suffering and brooding, he wanted to “understand this damned world, but couldn’t”. Then he came across Pascal: “Did his speech about the dark, hidden God explain to me what I had learned so powerfully, namely that violence and lies rule the world?”

Pascal joined this merciless doctrine of grace because he had seen through its absurdity

On the night of November 23, 1654, Pascal had a religious inspiration, which he testified: “Fire – God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, not of philosophers and scholars.” Flasch shows that it was less the Yahweh of the Old Testament forefathers who gave Pascal “certainty, joy and peace” than the theology of the late Augustine. Flasch had already subjected this to a precise ideological criticism in his book “Logic of Terror” (1995). The late Augustine was the inventor of a doctrine of original sin, according to which all people deserve divine wrath because they sinned “in Adam” – because the original sin of the first person is passed on from generation to generation through sexual intercourse, like a metaphysical HI virus passed on. All are therefore worthy of damnation except for a very few whom God destined for salvation before the beginning of the world.

Pascal joined this merciless doctrine of grace, although – no, because he had seen through its absurdity. Because for him human misery was so overwhelming that it could only be explained by this cryptic doctrine. Only in this way could the righteousness of God be saved for him. For how else should one understand the suffering of innocent children today – unless they are not innocent at all, but sinners, whom the wrath of God rightly hits? With a strange delight in paradox, Pascal dared a breakneck leap into a terrible belief: “This madness is wiser than all human wisdom. His whole state depends on this incomprehensible point.”

Kurt Flasch: Christianity and Enlightenment. Voltaire versus Pascal. Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2020. 436 pages, 49 euros.

As repulsive as this teaching is, it can also be fascinating. In any case, Voltaire worked on her all his life and wrestled with Pascal. In doing so, he aimed at a freer understanding of religion, not at its destruction. Therefore, like later enlightened Protestantism in Germany, he wanted to overcome the Augustinian distortion of faith. Contrary to what a popular cliché of conservative theologians asserts, however, he did not represent an optimistic worldview or a “superficial” understanding of faith. Who wanted to measure the “depth” or the “flat” here?

Voltaire, as Flasch shows, showed more seriousness and a sense of responsibility than Pascal, because in the face of the riddles of the world he did not flee into paradox, but instead asked himself elementary questions. When Pascal demanded: “One recognizes the truth of religion in the darkness of religion”, he countered: “These are strange marks of truth. How then is it different from a lie?” When Pascal declared: “God is hidden. Therefore, no religion that does not say that God is hidden is the true one”, he replied coolly: “Why always aim for God to be hidden? It would be much nicer, he would be manifest. ” And against Pascal’s demonization of the image of God, he set this creed: “One must love the creatures, and indeed very tenderly. One must love one’s country, one’s wife, one’s father, one’s children. One must love them so much because God makes that we love them against our interests. The contrary principles lead to nothing but barbaric nagging. ” That is why Voltaire reduced faith to what was essential for him. He focused it on what serves life: “Christianity teaches nothing but simplicity, humanity, charity.”

Flasch takes up some of the older publications in the book. In 2008 he gave a foretaste of his Pascal-Voltaire interpretation in “Battlegrounds of Philosophy. Great Controversies from Augustine to Voltaire”. Now he delves much deeper into this argument. The result is a workbook that sometimes looks like a slip of paper, takes many detours, digs, digs and ponders. Some things are reminiscent of his astute and successful criticism of German mediation theologies “Why I am not a Christian” (2013), but the tone is somewhat different. Because with unmistakable sympathy Flasch accompanies his “hero” in his attempts to shape a transformation of Christianity and to transform it from a misanthropic ideology back into a simple, good faith. However, when asked whether Voltaire succeeded in doing this in the end, Flasch gave no answer. It makes sense, because the enlightenment of Christianity is also a lifelong, individual task with an open outcome. It is enough to see the dedication with which Voltaire devoted himself to her.