Society

/

StudentNation

/

February 22, 2024

Over a dozen states reimburse services provided by these nonmedical professionals before, during, and after birth under Medicaid. But with this coverage comes new regulations.

A mother holds her baby at their home in Houston, Tex. The mother and her husband planned to have a natural childbirth with the help of a doula.

(Jahi Chikwendiu / Getty)

In 2022, after already reporting the worst infant and maternal mortality rates among high-income countries, the United States saw its infant mortality rate rise for the first time in two decades. These outcomes were gravest for Black Americans, who are three times more likely than white Americans to die from pregnancy-related complications.

As a doula in Louisiana, Brianna Betton witnesses these statistics play out. “It was surprising to see it in action,” she said, “seeing women’s voices be ignored, their bodies being touched without consent, their pain being ignored across the board.”

She decided to become a doula—a nonmedical professional who provides emotional, physical, and informational support before, during, and after birth—after learning that doula care could lower rates of cesarean delivery, preterm birth, and low birthweight. As a Black woman, Betton finds it especially important to serve patients who look like her, to make sure they have somebody in the room who “speaks like” them and “understands their needs,” she said. However, to fulfill her mission in underinsured and uninsured communities of color, she often has to provide pro bono services or a sliding scale for payment—which isn’t a financially sustainable business model.

Doulas often cost up to $2,000 and have traditionally been a “luxury” that only communities that were predominately white and of high socioeconomic status could access, explained Betton, who is also chief operating officer of the Doula Network. But many states are working to change that.

In December, Massachusetts became the 13th state to cover doula services under Medicaid, and 11 others are preparing to launch their own programs. Amy Chen, a senior attorney who leads the National Health Law Program’s Doula Medicaid Project, has seen a steady increase in the number of doula-related bills proposed each year since 2018.

States seem eager for doulas to fix birth outcomes in the most vulnerable communities. And, for the most part, doulas are excited. Medicaid funds 41 percent of births in the country, meaning coverage would broaden access to care. “Having access to Medicaid reimbursement really allows being a doula to become a sustainable profession,” Betton said.

Current Issue

But Betton is still wary. After all, there’s a catch: Medicaid coverage doesn’t just come with money—it introduces new rules and restrictions on how doulas practice. It gives states unprecedented power over the profession.

Traditionally, doulas have operated at the community level, independent from the health care system. The government has never had to set standardized requirements for them to practice. But in order for state Medicaid programs to reimburse doulas, that’ll have to change and a whole new set of protocols will need to be worked out.

To pay practitioners—whether doctors, licensed psychologists or doulas—states are required to have a regulatory framework that defines what is “acceptable care,” said Maureen Corcoran, director of Ohio Medicaid. Doulas will need to prove they’re legit, through a certification process that often requires significant training and testing. It’s the first time states are formally defining a doula’s role and regulating their practice, and doulas hesitate to trust states with the task. They worry the added government oversight will leave them excluded and erased.

The government has a history of disparaging Black birthwork. Jessica Roach—who cofounded a Black women–led reproductive justice organization called Restoring Our Own Through Transformation—worries that Ohio will repeat these injustices. For example, Ohio Medicaid originally proposed a requirement for doctors to supervise doulas—which doulas vehemently opposed. They traditionally work for the patient, not the medical system.

“The whole concept of doulas, I would say, is still not fully understood by hospitals,” Corcoran said. While Ohio Medicaid has since dropped this proposal, the state made another, more controversial, move: assigning the Ohio Board of Nursing to oversee the regulation of doulas.

“Most labor and delivery nurses don’t have the slightest idea what a doula actually does,” said Michelle Drew—a certified nurse midwife, family nurse practitioner, and expert historian who holds a doctorate in nursing. Nurses frequently consider doulas their “enemy,” she added, speaking from her own hospital experience. The relationship between nurses and doulas can turn adversarial when doulas advocate for their clients’ rights to be respected, she said, especially in the case of Black patients—two-thirds of whom report receiving “disrespectful care” in the birth setting. Drew added that more than 80 percent of the nation’s nurses are white, while the communities hit hardest by the maternal health crisis are of color.

Doulas are patient advocates, Roach explained, and allowing the medical system to control them would threaten that role, especially when it comes to protecting people of color. “Placing the regulation and definition of ‘scope of practice’ under the Board of Nursing may unfortunately eliminate the autonomy and some of [doulas’] ability to perform their duties effectively, especially Black Doulas,” Roach said. “I cannot begin to quantify how many times we, as an organization, have had to step in to address significant medical missteps that could have led to a fatality, as well as blatant mistreatment, neglect, and disregard for our humanity.” To Drew, the situation is an “obvious parallel” to the elimination of Black midwives in the 1900s.

In 1921, there were around 100,000 practicing midwives in the United States. The majority were Black midwives from the South who, in the Jim Crow era of racial segregation, were not formally educated, Drew explained. At the time, most African Americans, barred from attending school with white students, did not have an education beyond third or fourth grade. The tradition of Black midwifery was passed down under an apprenticeship system—the same way one might have learned to be a carpenter, welder, or any other skilled trade. “It’s not to say that they weren’t educated because they were,” said Drew. Within a community, older, experienced midwives would train the next generation, continuing a chain of inheritance that started when midwives first arrived in North America through the African slave trade.

However, as childbirth shifted from the home to the hospital, the government began to regulate Black midwives out of work.

Smeared with racist tropes, Black midwives were stereotyped as “ignorant” and “dirty,” and blamed for high infant mortality rates—despite research determining the opposite. “A workforce of people that were mostly Black women were easy to demonize,” Drew said.

The rising field of obstetrics, dominated by white men, campaigned to eliminate midwifery. States, with federal funding from the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, created a new licensing system and set their own requirements for education and training. By 1940, nearly every state required lay midwives to have permits to practice. Local departments of public health hired nurses, who were white and often significantly younger than the Black midwives, to oversee training for midwives. “They were looking to regulate them, and slowly but surely, to eliminate them,” Drew added.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

At the same time, a new workforce was being created: nurses with formal training in obstetrics and gynecology. A woman named Mary Breckinridge founded one of the first training programs, called the Frontier Nursing University, which only employed and trained white nurses. Nurse midwifery was a domain of white women.

In contrast, Black women who had spent decades caring for their community were suddenly no longer allowed to attend births. By 1978, there were no Black midwives practicing. “The beginning of the end of Black midwives was regulation and supervision by a white nurse or white nurse workforce,” Drew said.

The doula community has already regulated itself for decades, explained Olivia Atley, a member of the Ohio Doulas. There are many doula organizations that offer training and certification, with the first founded in 1992. She herself has trained with three entities, including Roach’s Restoring Our Own Through Transformation and the National Black Doulas Association, both dedicated to reproductive justice and fighting the Black maternal health crisis.

She finds it insulting that, after receiving three trainings from reputable doula organizations, she would need an additional national or statewide “credential” in order to make her valid. Ohio, where she practices, has yet to decide which existing groups, if any, it will let certify doulas. “They want to try to separate us so that they can control the narrative, they can control our work, and they can control how we interact with patients,” said Atley. She would rather see a panel of experienced doulas in charge of evaluating and governing doulas.

Ohio is currently the only state that is housing the doula certification under the Board of Nursing. Roach, who has over 25 years of experience in clinical healthcare and research, midwifery, public health, and public policy, wishes the state had instead created a separate entity for all community birthworkers, such as lactation consultants, certified breastfeeding educators, and doulas. “My advice is always the same, consult actual subject matter experts rather than individuals with titles that make you feel comfortable,” she said.

The Ohio Board of Nursing did not respond to requests for comment. Corcoran, however, on behalf of Ohio Medicaid, argued that this separation will give doulas flexibility to help define their new provider type. The state is also currently setting up a Doula Advisory Board. She emphasized that the point of certification is to establish a minimum level of experience and capability, to ensure people are qualified to practice. “They want to be sure that the regulations are going to be reasonable, that we’re not going to expect that they all have PhDs, and they all have delivered 500 babies,” Corcoran said. “We’re very sensitive to that.”

Keisha Goode, a sociologist and historian of Black midwifery at the State University of New York– Old Westbury, agreed that credentials can have value. They ensure that people are trained. However, too often, “credentials get weaponized as tools of social closure,” she said. How will Ohio decide what it means to know something or who we deem as an expert? “Training doesn’t always have to look like ‘x’ institution,” she said, instead arguing in favor of a more formalized apprenticeship model where education is based on competency.

Betton highlighted California, which provides both a training pathway and an experience pathway, where doulas with five years of experience can simply provide letters of recommendation from former clients. Doulas are also hoping states will recognize the doula-led training programs that have existed for decades. Some of the most experienced doulas have already invested thousands of dollars and countless hours in training—with the certificates to prove it. “What is formalized doula training? And how does that leave out a whole host of people who’ve been doing the work for a while?” Betton said.

Ohio’s doulas are finding themselves in an uncomfortable position. Relinquishing power to the government may threaten their role as patient advocates, whose core work lies with clients, outside of the medical model and the healthcare system. Doulas are community health workers, Goode emphasized. They recenter “bodily autonomy and integrity and humanity and person centeredness and relationship centeredness” within a medical model that views pregnancy as a medical condition or illness.

“The only concern that most doulas have is that we don’t want to work for the medical providers,” said Cynthia Hayes, a doula from Connecticut. “We want to work for the family.” Doulas could be a promising solution to the maternal health crisis—if states let them.

More from The Nation

America eats its young through legislation that valorizes bullying.

Dave Zirin

Republicans are working hard to destroy our public health infrastructure. Too many Democrats are helping them. It needs to stop now.

Gregg Gonsalves

A small but influential group of trans journalists are covering trans issues in a way that too many leading outlets refuse to do.

Emmet Fraizer

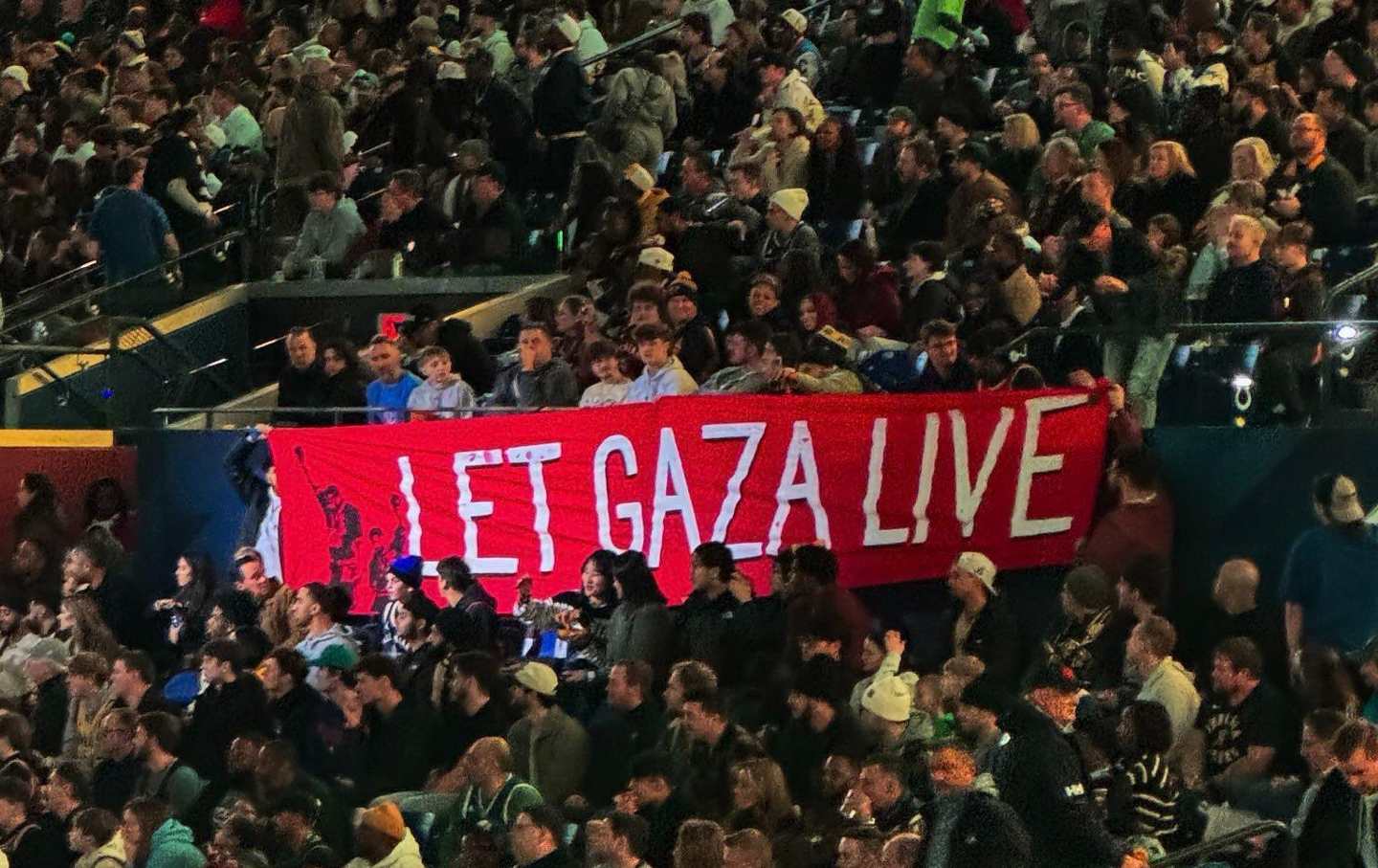

Members of the Palestinian Youth Movement and Jewish Voice for Peace unfurled a banner that read “Let Gaza Live.”

Dave Zirin

There are few things more important for people in prison than keeping links with the outside world. That task falls overwhelmingly to women.

Rachel Zarrow and Christopher Blackwell

Cameras aren’t just monitoring us in public—now they’re actually yelling at us.

Column

/

Kate Wagner