When they write the book on the downfall of liberal democracy, will it begin with the heat pumps?

Immediately outside the main train station in the German city of Wiesbaden, an election poster has been tied high up on a lamppost, out of reach of those who would tear it down in the belief that it’s a harbinger of fascism once again spreading across the country. The subject? Not scary depictions of migrants. Nor the overreach of the European Union. But home heating systems.

The heat pump, a banal piece of green home technology, was at the center of Germany’s major political controversy of the summer — one that has helped propel the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) to the brink of a series of electoral breakthroughs, prompting many in a country scarred by the legacy of Nazism to fret about the future of democracy.

The next Rubicon moment could come as soon as Sunday when elections are held in the German state of Hesse, where the party has seen a surge of support in part because of controversy over heat pumps. I met the man responsible for the heating placard, Robert Lambrou, the local leader of the AfD, at a campaign stand in a shopping center parking lot on the plush outskirts of the city.

A tall man with a lopsided smirk and the eyes of a Greek fisherman, the party boss was in a buoyant mood. If things go well for the AfD this weekend, the party — a political project increasingly dominated by a radical wing of extremists, climate-change deniers and ethno-nationalists — could romp into the state parliament as the second-largest political force. Such a showing in Hesse would mark the party’s most significant success outside its traditional heartland in former East Germany; and it would vindicate its decision to weave climate change policy alongside migration and Euroskepticism into its grand narrative of decay, elitism and rage.

“Here in West Germany, for the first time in 10 years, something is moving,” Lambrou said. For some of his new voters, he claimed, the heat pump furor — which occurred after the government introduced a law phasing out fossil fuel heating systems — was the final drop that tipped the bucket over. Across the country, the AfD can now claim the support of one in five German voters.

The far-right’s ability to turn a debate on heating systems into electoral rocket fuel has implications that go far beyond Hesse. Across Europe, the far right is gaining ground and in many places making opposition to climate policies a core issue. It’s a development that has caught the eye of politicians across the Continent, especially in conservative parties that have jettisoned their green commitments in the face of the populist assault.

In the U.K. last month, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, a Conservative, walked back his own bans on gas boilers as well as petrol and diesel cars, warning “we risk losing the consent of the British people.” On Monday, his new energy secretary, Claire Coutinho, explicitly cited the AfD’s rise as a cautionary tale to argue against what the U.K. government now sees as an overly ambitious climate agenda. European Parliament President Roberta Metsola has warned that climate regulations must be tempered in the face of populism. Her center-right European People’s Party, the largest group in the Parliament, has attacked a series of Brussels climate reforms.

As this retreat gathers pace, so does the popularity of the AfD, and with it the sense democracy — or the liveability of the planet, or both — is under threat. And so I went to Germany to try and understand why and how the heat pump, of all things, had become the new horseman of the far right.

Catalytic converter

The political storm that almost tore the German government apart began in April, when the ruling federal coalition of Social Democrats (SPD), Greens, and liberals proposed the Building Energy Act, a law aimed at banning the installation of gas boilers from next year. Heat pumps run on electricity and are much less polluting, but they are, as of now, significantly more expensive to install than fossil fuel systems.

The cost of a heat pump can vary wildly: from as little as €9,000 to as much as €120,000 depending on the type and the difficulty of installation. The AfD focuses on the upper end of these estimates. But Katja Weinholt, a spokesperson for the German heat pump trade association BWP, said a household that would spend €10,000 on a gas boiler might now pay €35,000 for a standard heat pump. And with current subsidies, the total cost to the consumer comes down to something more like €17,000 to €18,000.

The blowback to the law was fierce and immediate. The term “heizhammer,” the heating hammer, became a relentless refrain in a campaign by Bild (a tabloid owned by Axel Springer, POLITICO’s parent company), and the accompanying uproar precipitated an embarrassing climb down by the Greens Economy Minister Robert Habeck. The law the parliament eventually passed in September pushed the phase-out back by two to four years and accommodated the installation of new fossil fuel boilers beyond those dates, so long as they can be switched to hydrogen — a fuel some experts say has dubious prospects for widespread use in home heating.

The fudge dismayed climate experts, and even officials in Habeck’s ministry, who said Germany would be unable to meet its commitments to cut greenhouse gases without aggressively tackling pollution from buildings, which produce roughly a sixth of all the country’s emissions.

GERMANY NATIONAL PARLIAMENT ELECTION POLL OF POLLS

For more polling data from across Europe visit POLITICO Poll of Polls.

Even before the heating law was introduced, the AfD had been rising in the polls. But support surged as the party made the law a central pillar of its campaigning. The AfD is now at 21 percent nationally, according to POLITICO’s Poll of Polls, double the vote share it received in the 2021 federal election and comfortably the second-largest party in Germany. In several eastern states, some of which have elections next year, the party holds a huge lead. In Hesse, the state that houses the European financial center of Frankfurt, it’s at 16 percent.

The AfD’s success can’t be laid completely on the heating law. But while migration remains the chief reason voters back the party, polling from some states suggests the heating law is now a close second.

The heating law was “a katalysator” — a catalyst — the Hessian party boss said. “It was maybe the final kick for people who were very unsatisfied before,” he added, speaking the English he learned on an exchange to San Francisco in 1982.

Since it was proposed in the spring, Lambrou told me, AfD membership in Hesse grew by almost 50 percent.

(R)evolution

Lambrou insists he has no truck with the part of the AfD that flirts with Nazi ideology. But his own journey, from a disaffected social democrat to carrying water for demagogues, shows how one issue can act as a gateway into once unthinkable politics.

Lambrou is no tub-thumping firebrand. Before politics, he was corporate vice president of a firm that makes snow plows and street sweepers. Today, this polite, angry middle manager is leading a far-right charge into the heart of Germany’s polite, angry, middle class.

When he first attended a meeting of the AfD in a “crowded-like-hell” town hall in March 2013, it was a party with a single cause: opposition to then Chancellor Angela Merkel’s commitment to bail out struggling eurozone economies like Greece. Merkel’s claim that the policy was “alternativlos” — literally alternative-less — gave the new party its name. “That triggered so many people in Germany,” Lambrou said.

At that moment, Lambrou was politically homeless. After being a Greens voter as a 1980s youth — “environment protection was important to me and is important to me,” he explained — he voted for the center-left SPD in every election for 20 years. But when the SPD, along with the rest of the political mainstream, backed Merkel’s bailout of the Greeks with German money, it felt to him as if everyone around him had become untethered from reality. Lambrou, whose own father is Greek, was convinced the country should have instead been kicked out of the currency.

Several AfD members I spoke to described their early encounters with the party as something akin to joining a therapy group. Suddenly they found a space where views that their families and friends frowned on were accepted.

For Lambrou, his first meeting was a revelation. He had been delayed by snow and arrived late to find room only to stand at the very back. He had the sense that something both momentous and utterly normal was taking place. “It was very rational, very reliable, very good political positions,” he said. “The people who were in the audience were absolutely civil.” He signed up that night.

The platform the AfD took to elections that year called for the dissolution of the eurozone. But in most other policy areas it was thin. The only gesture to climate policy was a demand for renewable energy subsidies to come from taxation rather than bills.

Over the following years, the membership grew “like a Cambrian explosion,” said Lambrou. But new members were attracted by, or pushed the party toward, increasingly hard-line positions, especially as the 2015 migration crisis — when Germany accepted more than half a million asylum seekers from mostly poor, Muslim nations — sent some in the country into a panic.

Lambrou’s views developed alongside the AfD’s. “You have to understand that at the center of the worry of many people is mainly the mass migration,” he said. “They fear the loss of their home like they know it. They fear a change of the cultural identity of Germany. And the fear is well reasoned.”

Even as extremists who adhere to a blood-and-soil vision for Germany have gained sway within the AfD, Lambrou has stuck around, hoping it will become more moderate with time. “He’s quite a nice man,” one former AfD leader said about Lambrou. ”But he makes his peace with everything.”

Getting religion

It was only in 2019 that the AfD established climate change as the next bugaboo for its growing base.

That summer was the peak of Greta Thunberg’s fame and power. Her youth-led campaign was compelling leaders from across the political landscape to shift their stance on climate change.

At a two-day meeting in Dresden in July, a group of AfD environmental officials met to work out their response. For them, the issue fit into a grander narrative –– of Germany as a country at risk of being eroded away. “They actively identified it as a site of political polarization,” said Bernhard Forchtner, an expert in far-right communication on climate change at the University of Leicester.

An eight-page declaration the Dresden group released set the party on a new course. At the European Parliament election that year, the AfD ran on a three-pronged platform: opposing migration, the euro and climate action.

The stance the party adopted on climate science was extreme, even compared with that of other European far-right parties. The AfD claimed there is no evidence that humanity is changing the climate, at least not to the degree that it is worth doing anything about. Espousing a falsehood that ignores decades of scientific research, the AfD instead cited a host of cranks and grifters who have cast doubt on the widespread consensus. “The far right is usually not rejecting science, per se,” said Balša Lubarda, the author of the book “Far Right Ecologism.” “‘What they’re usually doing is they’re trying to offer an alternative science.”

For this article, POLITICO interviewed 12 AfD members, supporters and officials. Almost without exception, they expressed some version of the view that it is the AfD guarding the gates of reason, while the zealotry of climate activists threatens to tear the world apart.

After Sunak echoed this sentiment last month in the U.K., saying that those looking for faster progress were blinded by “ideological zeal,” AfD officials told me the British Prime Minister had got it just right. Green politics has become a “religion,” Lambrou said.

“I do not know anybody who is afraid of [the AfD’s national co-leaders] Tino Chrupalla or Alice Weidel,” he said, slowly sliding his blue tie between his thumb and forefinger as though measuring it over and over again. “I do know a lot of people who are really afraid of Robert Habeck [the Green minister] and the suicide politics regarding economics and the total ignorance about the true worries of many people.”

Identity politics

For many of the AfD’s true believers, the worry runs deeper than the hip pocket. They see it as part of a battle for Germany itself.

At the campaign stand in Wiesbaden, along with Lambrou, a cluster of seven volunteers and party hacks — all of them men — milled about, occasionally talking to passers-by, but mostly just talking to each other. One of them was Henry Ballandies, a local realtor with white hair and thin lips who didn’t so much shake my hand as rearrange it. He joined the AfD two years ago to do something for the country, “before it crashes.”

Over a coffee at a bakery across the street, Ballandies told me that 40 years of selling homes in one of Germany’s richest cities had left him with no personal financial worries. But he shared the view laid out by the 2019 Dresden Declaration, which warned, without evidence, that the coming attempt to rid the economy of fossil fuels was a veil for the establishment of an eco-dictatorship.

“This is the way to socialism in Germany,” said Ballandies. “They tell you which car you have to drive, what heating you have to use and what you have to eat and everything. It’s no more a free country.”

For Germans like Ballandies, costly climate policies, combined with high energy costs and inflation, deepen their sense that the mittelstand — the fabled small and medium-sized companies that are largely credited with Germany’s post-war economic miracle — is being undermined. That poses a challenge to how Germans of a certain age and social status see themselves. Ballandies, who, for sentimental reasons, still carries Deutsche Marks in his wallet, despite them being replaced by the euro more than two decades ago, described his horror at seeing older people collecting bottles from recycling bins to cash them in. “It’s not [any] longer the Germany I know from former times,” he said.

“The AfD really taps into the fears of loss; loss of status, loss of identity, loss of prosperity, wealth, and comfort,” said Joe Düker, who analyzes far-right online discourse at the Berlin-based Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy. “The AfD comes in and says, ‘Well, we want to go back to how it was. We want to maintain the status quo.’”

Two AfD officials told me in private that their views on climate science were much closer to the mainstream than the official party line. But the curtailment of freedom trumped these concerns. “I would prefer climate change to a one-world government,” said one of them.

This sentiment is probably closer to AfD’s real objection to climate legislation. The fear that links heat pumps to migrants, the euro to transgender people, is of a world out of their control, being recast by global elites.

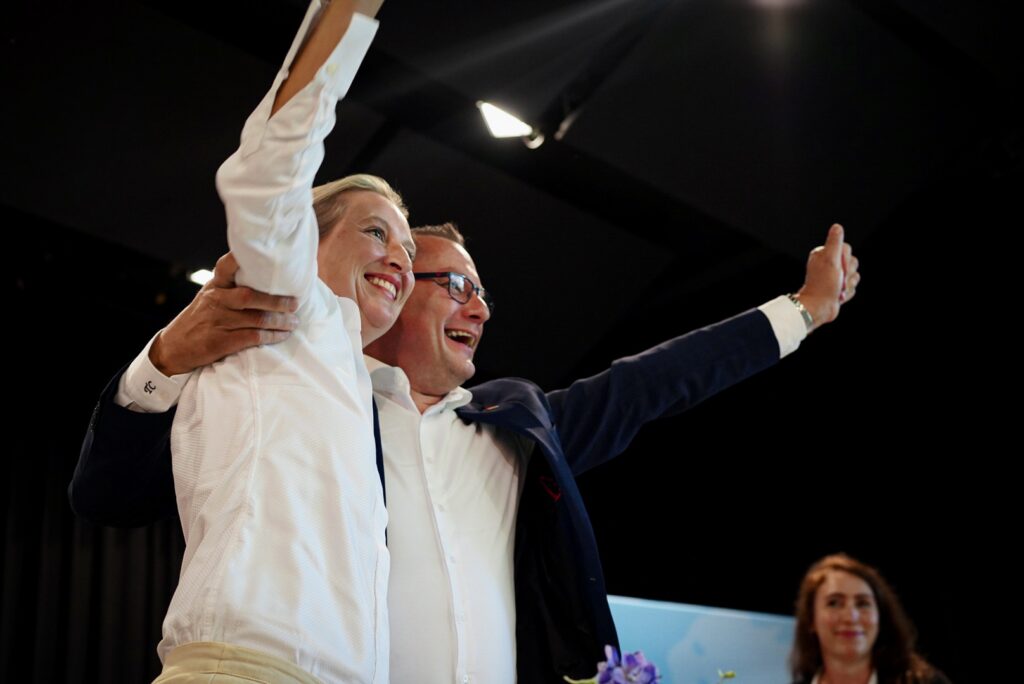

“We are being bullied,” the AfD national co-leader Weidel told a sweaty crowd in a multifunction sport and event hall in Gelnhausen in early September as she launched the campaign for the Hesse state election.

“The citizen is no longer free to decide which heating system he wants to have in his cellar,” she said. “But we are allowed to choose once a year whether we want to be male or female or anything else.”

Right-wing takeover

AfD members’ embrace of the belief that they are heroes in a war for the preservation of Germany has coincided with the rise of the truly hardcore among its members.

Lambrou and several other party officials insist that the original cohort of economic liberals still have control over the party’s direction. But rather than acting as gatekeepers against extremists, they increasingly look like doormen, ushering them in.

This summer’s party congress marked a victory for Björn Höcke, the head of the party’s extreme branch in the former East German state of Thuringia. Höcke was able to install one of his close allies, Maximilian Krah, at the head of the party’s list for next year’s EU elections.

“The right-wing guys took over,” said the former AfD leader, who asked not to be named in this article because of the fear of retribution. “The dominant person in the AfD nowadays is not Weidel, it’s not Chrupalla … but Höcke.”

In his time as state party leader, Höcke has repeatedly pushed the limits of what German voters were thought to be willing to accept, and he’s come away stronger for it. In July, a court ruled that when a protester had called Höcke a Nazi, they were making “a value judgment based on facts.” (That reinforced a previous ruling that said describing him as a “fascist” was not libelous.) The head of the Thuringian intelligence services, who is Jewish, said in June that he would leave Germany if the AfD were ever to enter government. Höcke did not reply to an email asking him for comment.

What Höcke wants for Germany is a rupture. Last month in a post on X, formerly Twitter, he called for “regime change.” And when it comes to the environment, he embraces thinkers who want to combine a vision of an ethnically German homeland with clean rivers, organic farms and pine-clad Alps — an almost deified notion of pure Volk and pure nature reminiscent of Nazi ideology.

One morning in May 2020, Höcke posted a picture of himself on Facebook. He was posed amid the trappings of an uneaten country breakfast, gray hair swept to the side, sipping from a coffee cup and reading the first issue of Die Kehre — an elegantly designed quarterly magazine dedicated to reclaiming ecology for the far right.

To understand the message Höcke was sending, I called the magazine’s editor-in-chief, Jonas Schick, a 33-year-old with a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Bremen. Shick is part of an intellectual milieu that calls itself the New Right, which stands slightly to the side of the AfD, but is closely intertwined with the party. AfD luminaries regularly make the pilgrimage to the group’s regular salons, held in a manor house in the village of Schnellroda in Saxony-Anhalt. Schick himself works in the office of René Springer, an AfD Bundestag MP.

Schick speaks in a friendly and open manner and, in online videos, looks more like a guy you’d find working in a Berlin coffee shop than someone building a green ideological platform for the end of the liberal order. He is a climate “skeptic,” he said. But not quite for the same reasons as garden variety climate deniers. The solutions being proposed by governments to slow down global warming — wind farms, solar panels and heat pumps — are “another face of the industrial consumerist society” that he wants to tear down.

In the pages of Die Kehre, Schick pushes for the creation of a society based on ethnically homogenous cultural units, focused on rural pursuits. Technological and economic progress would be supplanted by stability and circularity, he said. His enemies, the liberals that have opened borders to foreigners, are also the consumerist, capitalist “powers who destroyed old traditions and also destroy the nature.”

Schick has also been deeply involved in the identitarian movement. This group seeks a society with “ethnic continuity,” he said. “If there is a lot of change within groups, there’s no form of real stability and possibility to really form a stable cultural framework.” In other words, he’s into white nationalism.

‘Only the start’

There’s a thin but sturdy thread that runs from Schick and the other radicals in Schnellroda to the wealthy curmudgeons and political glad-handers I met in Wiesbaden: the resistance to change, the desire to seek safety in a shared embrace of retrograde fantasies about an idealized past — an alternative reality — rather than grapple with the challenges of the world as it is.

When it comes to climate change, the potential for a dangerously delusive kind of nostalgia is clear. It may be easier to believe an eco-dictatorship is upon us than to accept the reality that life as we have known it is fundamentally threatened by global warming.

It’s a sentiment that anybody looking to rein in global warming needs to be aware of, as the effort necessitates the wholesale remaking of the energy foundations of our economies — from where our power is produced, to whether consumption can be reduced, to, yes, how we fuel our cars, feed our children and heat our homes.

After the heating law blew up, Habeck, the climate minister, told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper in June that he did not sense how fragile and change-weary Germans had become. “Across society, there is a feeling of fatigue due to the many crises of the past few years,” he said. “After COVID or the war in Ukraine, the climate crisis or the rise of the populists, you think: What kind of times are we living in? And now, in this atmosphere, such a law is introduced.”

Efforts to slow down climate change won’t automatically trigger a rise of the right. There are countless examples of interventions that lower carbon pollution that are wildly popular — or at least benignly ignored — from solar feed-in tariffs to emissions standards for cars. And even if voters sometimes blink on certain measures, the public still enthusiastically supports climate action, especially when politicians make the effort to sell it in terms that resonate with conservative values, like patriotism and economic might.

In the U.S., President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act explicitly challenged China’s clean energy dominance and heavily favored Republican states with its subsidy largesse. Last week in France, President Emmanuel Macron rolled out his own heat pump strategy with a focus on building a homegrown manufacturing sector and training 30,000 French installers. And even as Sunak rolls back the U.K.’s commitments, the Labour Party, which is expected to form the next British government, is trumpeting its proposal for Great British Energy — a national renewable energy company — ahead of next year’s election.

What’s clear, however, is that there are real concerns among voters about the cost of some measures, just as there’s resistance to policies being presented not as a choice but as a diktat. After a short period of consensus that the world must band together to stop climate change, the lesson from Germany is that the next stage of the fight against climate change will take place on perilous ground and that policies will fail, unless they are crafted with care to make them less vulnerable to populist blowback.

In Wiesbaden, I found Lambrou excited about the success of his party’s new message and optimistic about the future. “It could be that this is only the start,” he told me. “You cannot make politics against [your] own people.”

Peter Wilke contributed reporting from Wiesbaden and Gelnhausen.