Josep Borrell made half-hearted efforts at best to spread optimism. His proposals on how the EU should deal with China were well received, said the European Union’s foreign policy representative a few days ago after a meeting of European foreign ministers in Stockholm. The talks were “not easy”. But all 27 member countries agree that Europe needs to recalibrate its China strategy. Everyone sees that Beijing is behaving less like a partner and more like a “systemic rival”. And that it is necessary to reduce the EU’s dangerous economic dependency on China for important raw materials and modern technologies – keyword “de-risking”.

How far this unity goes in practice could be seen on Sunday. The Hungarian government tweeted pictures of Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó boarding a Learjet. Szijjártó, it was said, was on his way to Beijing to talk “about the advantages of cooperation with China” and about “the opportunities that both sides offer”. Not a word about de-risking or even systemic rivalry.

“If we don’t speak with one voice, the Chinese will eat us for breakfast.”

Borrell describes such cracks in European unity as “nuances”. But this word acrobatics does not make the disagreement any less dangerous. “If we don’t speak with one voice, the Chinese will eat us for breakfast,” warns a diplomat in Brussels. Because Beijing has no interest in the EU making itself more independent of China and standing by Washington’s side, where de-risking has long been the talk of the town, but rather “decoupling,” a far-reaching decoupling. Beijing’s counter-strategy is to widen and exploit the cracks in Europe – for example, by specifically wooing individual EU members like Hungary.

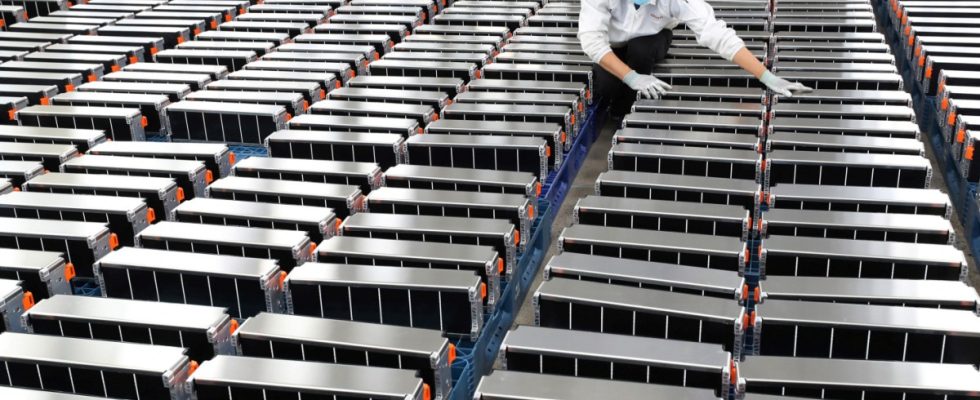

The driving force behind the European de-risking strategy is the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. Your authority has proposed a number of laws in recent months, all of which aim to reduce Europe’s dependence on Chinese supplies – for strategically important raw materials such as rare earths, but also for green and high technology such as batteries for electric cars and computer chips. This should minimize the risk of being taken hostage by Beijing for security reasons in the event of a conflict. “It’s about more resilience,” says a diplomat.

Partner? rivals? Some in Berlin have a clearer idea of the relationship with China than Chancellor Olaf Scholz (left), here in November during a visit to China’s President Xi.

(Photo: Kay Nietfeld/dpa)

For von der Leyen, this is the logical consequence of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The war has shown how dangerous it is for the EU to make itself economically dependent on an aggressive dictatorship. In the case of Russia, this dependency was limited to oil and gas supplies. Getting out of it was difficult and expensive. In the case of China, on the other hand, Europe’s dependency is much greater, it includes in one form or another almost everything you need to maintain a competitive economy or to convert it to be climate-neutral.

This is precisely what makes it so difficult for EU countries to agree on what de-risking means in reality – even if, as is expected, the heads of state and government officially defined the term at their summit in Brussels in late June should write in the closing statement. “The positions are still quite far apart here,” says a diplomat.

Some also want to sanction Chinese companies because of Russia’s war

This is also reflected in the working paper that Borrell wrote as a basis for discussion at the foreign ministers’ meeting in Stockholm last week. To a large extent, it consists of formulations in which all 27 EU countries can somehow find themselves. On the one hand, it is clear, says Borrell, that Beijing aims to change the Western world order, that it is using its economic power to be politically aggressive. On the other hand, Europe must continue to work with China where necessary and possible, for example on climate protection. Borrell’s paper for the foreign ministers sounds much more reserved than the speech in which Ursula von der Leyen presented her de-risking plans a few weeks ago.

In one specific case, this gap between the Commission and EU governments in terms of their willingness to confront Beijing is currently clearly visible: the Commission has proposed that the new sanctions package against Russia also include punitive measures against a handful of Chinese companies that use the Russian military and thereby supporting the war in Ukraine. In many EU capitals, however, there are serious concerns about alienating Beijing in this way. Berlin is not enthusiastic about the idea either.

Incidentally, the European consensus is not exactly promoted by the fact that the German government is still looking for its own China strategy internally. The range of positions in the EU corresponds pretty much exactly to the range of positions in the traffic light coalition, a diplomat in Brussels complains.

There is actually a wide gulf between the Greens around Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Economics Minister Robert Habeck, who want to take a rather tough approach to Beijing, and Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who approved the participation of a Chinese state-owned company in part of the port of Hamburg. Scholz uses the term de-risking himself, but likes to precede it with an adjective: “clever”. He seems to reserve the right to define what is stupid and what is smart de-risking in individual cases. Not everyone in Brussels thinks this is clever German leadership.

However, there are also observers in the EU who believe that Europe should not belittle itself when dealing with China. Beijing’s nervous response to the de-risking debate shows China has something to lose and the EU has leverage. In Brussels, for example, attention was paid to the fact that Beijing urgently wants to revive an agreement with the EU that is intended to facilitate mutual investments. The deal is on hold after Beijing issued travel bans against several MEPs who had criticized the oppression of Uyghurs in China.

Beijing recently offered Brussels to lift these sanctions – without demanding anything in return. That was a rather “un-Chinese” behavior, says a diplomat. “But the Chinese fear that the EU and the US will act as one. That’s why they want to split the West and Europe.”