In addition to the usual and inevitably completely analogue improvements to one’s own self – less alcohol, more yoga – the beginning of the year is also a time for self-discovery and reinvention in the digital space. Fitter, happier and of course more productive. A popular goal: to give the atrophied attention a little more, well, attention. Frustrated by the disappointments and failures, you look for better methods, systems or strategies to achieve your goals: A new plan is needed and maybe a new app.

Productivity programs of all stripes were downloaded more than seven billion times from the software stores of major tech companies in the past year. They have enticing names like Omni Focus, Any.do, or Todoist, and they’re all a promise. Ultimately, users expect nothing less than the answer to the question of what you should do now in order to achieve all of your goals: because the scarcest human resource is still time. At the same time, responsibility is delegated to our future selves, who will sort things out. “We like lists because we don’t want to die,” Umberto Eco once said mirror dictated into the block.

You may find that excessive. In any case, a very practical problem is that the most popular apps have come to pack a ton of features, resulting in a good chunk of time being spent in some odd sort of meta-organization. The programs allow a user to create tasks, schedule due dates, leave comments on the tasks, reorganize tasks, mark tasks as completed or incomplete, and assign tasks to different priorities.

We love managing tasks – instead of getting them done

The app sends notifications, SMS and emails about the current state of affairs. Herein lies the first, quite obvious, paradox. Because that means a lot of interruptions. And a lot of time spent managing your own tasks instead of getting them done. Weeks or months later, the apps often enough become a staggering pile of unfinished business, and every time you open them, you’re painfully reminded of your own failure.

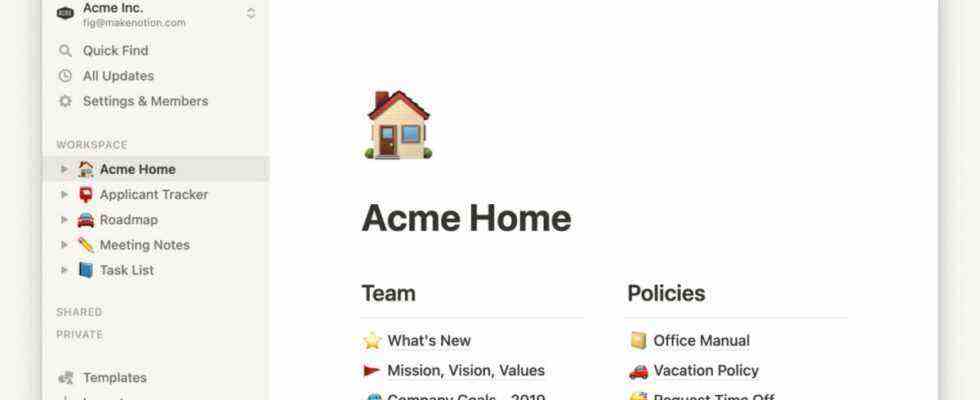

In the past year, a new, even more powerful variant of self-organization apps has become popular. They promise a total overview, all digital material that we create should be collected in one central place. The programs with names like Notion, Obsidian or Mem promise their users a “second brain, forever” or a “Google search for their mind”.

The dominance of the doers is well known. Like the filing cabinets of the pre-digital era, these apps are not only supposed to outsource everything our brain can’t absorb – shopping lists, passwords, meditation plans and deadlines – but they are also supposed to ensure that we can better retrieve the information they contain . There is now a halfway fanatical following on social media, numerous people are exchanging views on how best to organize their lives, there are even influencers who share their strategies, their videos have hundreds of thousands of views.

What is skilfully ignored in the subculture of self-organization is a second paradox. Namely, the unanimous promise of technology companies to relieve people of the decision-making process so that they have more time for the so-called essentials. But if you don’t really make any of these decisions yourself and autonomously, what is still important at all?