Old books, said the English writer Virginia Woolf, are like wild, homeless birds: “They gather in great flocks with many plumages, and possess an inherent charm that their tame counterparts in libraries lack.”

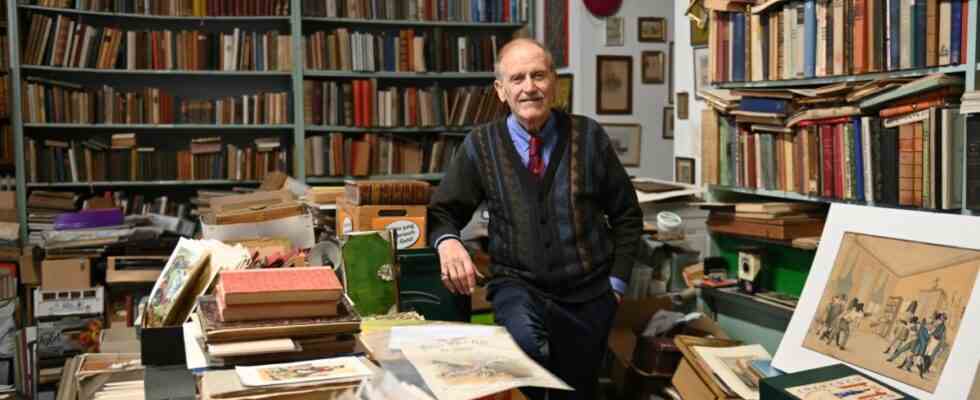

Such a swarm has settled at Schellingstrasse 99 in Munich-Schwabing, and its keeper is Rainer Köbelin. He loves old books. “The older they are, the better I like them,” he says. He especially loves beautiful books. A cover made of fine, red morocco leather, a beautiful endpaper, lovingly executed illustrations – these are, so to speak, the birds of paradise in his book swarm. “I would be extremely reluctant to throw away a book like that,” he says. And yet he foresees that this will one day be the fate of the wild books he has collected. He is 84 years old and one of the last of his kind: antiquarians who offer their books in a shop instead of selling them on the Internet. What will happen when he stops? “Waste paper,” he says. “Antiquarians are not for sale. These are the times, I’m a realist. Everything else is nonsense.”

Once he closes his shop, all the books will end up in the trash. Rainer Köbelin isn’t fooling himself.

(Photo: Stephan Rumpf)

In a certain way, Rainer Koebelin is a bird of paradise himself. Not because he likes to combine his brightly colored shirts with brightly patterned ties. Rainer Köbelin is someone who considers himself lucky because he has spent his life trying, mostly successfully, to only do what he enjoys. Old books are just one of three passions he indulges in. The other two are fencing and tap dancing.

How does that fit together – the contemplative, quiet world of books, the drama of fencing, the fast-paced clackedi-clickedi-clack of tap dancing? That may have something to do with Rainer Köbelin’s parents. His father, born in 1903, came from a farm in Baden, but he had nothing in common with agriculture. He wanted to be a journalist and was already writing for the in the 1930s Munich Latest Newsthe predecessor of Süddeutsche Zeitung. Very old and long-time SZ readers may still be familiar with the name Karl Köbelin: for 24 years, from 1946 until his retirement in 1970, he reported for the SZ from the Bavarian state parliament.

And Karl Köbelin was a book person. “He was a serious collector of old books,” reports his son Rainer. “The library was his sanctuary, we were confronted with books from an early age.” The son remembers that his father had “nothing to do with sport” except that he liked going to the mountains. “He was a very taciturn, humble person.”

The sporty and the artistic came more from the mother. Amanda Schwinzer, who performed under the stage name Marga Kalin, danced, sang and rode a wheel. Karl Köbelin met her when she appeared in the Munich cabaret “Bonbonniere” in 1931. “With a bold spirit,” the young lady “rushed here from Würzburg to produce herself in the studio,” she wrote Munich Telegram newspaper“she sang to the lute with a very likeable voice; as a tap dancer she caused even more furore later on”.

He wanted to learn to fencing like these devils

And so the son probably got his aversion to activities that involve sitting still for a long time from his mother. “The school” – the humanistic Theresiengymnasium – “was absolutely repugnant to me,” says Rainer Köbelin. He decided not to take his Abitur, preferring to go to the cinema. He was fascinated by the coat and sword films of the 40s and 50s, “The Three Musketeers”, “Robin Hood, King of the Vagabonds”, “Zorro”, “The Lord of the Seven Seas”. He also wanted to learn to fence like these devils. Later photos show him with a menjou beard, just like his screen idol Errol Flynn.

But how should he start? “You can do that later when you’re earning money,” his father told him.

But Rainer Köbelin is not one to give up easily. In a small antiquarian bookshop on Lindwurmstraße he found a fencing textbook by a certain Carl Stritesky: “Saberfechten – Schule und Kampf”. “The best fencing book I’ve ever had,” says Rainer Köbelin, and that’s saying something, because he now has several hundred. This Stritesky was a university fencing champion and fencing teacher at the men’s gymnastics club (MTV) in Munich. Koebelin introduced himself to him, and Stritesky, in a friendly mood because the young man liked his fencing book so much, took him on as a pupil. Rainer Köbelin and fencing – that became a love for life.

Fencing – a love for life. The 84-year-old still teaches stage fencing today.

(Photo: Stephan Rumpf)

Even today, at the age of 84, he gives lessons in stage fencing at Studio Mandolin on Grillparzerstrasse in Haidhausen. “I never wanted to win tournaments,” he says, “I like fencing as such.” In stage fencing it is important that the audience gets something to see, unlike in modern sport fencing where the action happens so fast that no one notices what is happening. And so he practices with his students the classic attacks and parries – prim, seconde, third, fourth, fifth – and the fencing etiquette, the greeting ceremonies of the cadets and the musketeers at the French royal court, and it’s a lot of fun for him.

Theory to practice: Of course, there are numerous works on the art of fencing in the Köbelin antiquarian bookshop.

(Photo: Florian Peljak)

There was something else to see in the cinema that fascinated Rainer Köbelin: tap dancing. Gene Kelly in “An American in Paris”, Fred Astaire in “Singin’ in the Rain”. He was also predisposed to tap dancing from his mother. So he also took tap dancing lessons. He often went to Paris, there was “the only dealer who only dealt in fencing articles”. There Rainer Köbelin laid the foundation for his phenomenal collection of fencing articles and fencing literature. And as luck would have it – in Paris he met one of the world’s best tap dancers, George Taps King, a Tunisian who had even performed as Gene Kelly’s partner, “a total fanatic, just like me”. For many years Rainer Köbelin was active as a tap dancer, together with George Taps King he performed in Munich at the Theater an der Leopoldstraße. That also brought in a bit of money, because he didn’t really have a secure financial livelihood yet. He got through life with all sorts of jobs and he didn’t need a lot of money because he still lived in the Hotel Mama.

A Munich resident in Paris: That’s where Rainer Köbelin meets one of the world’s best tap dancers.

(Photo: private)

In 1967, when Rainer Köbelin was 29 years old, he opened his own antiquarian bookshop on Amalienstrasse. It was a fairly small room, and his inventory consisted of two laundry baskets full of old books, mostly children’s books, that he had bought together. A friend, also an antiquarian, gave him some goods on commission. “Back then you went to a book appointment twice a week, when your grandfather died and the heirs didn’t know what to do with the books”. That’s how it developed. He stayed in Amalienstrasse for 17 years, but then the homeowner preferred to have a restaurant on his property, which was probably more lucrative. Rainer Köbelin moved to Schellingstrasse 99. That was, he says, “at the dead end of Schellingstrasse,” no longer really in the university district where antique shops are actually based, but the rent was affordable.

In those 70s, 80s and even 90s of the last century, the trade in old books was something that magically attracted enthusiasts. Anyone who collected old books – be it old cookbooks, children’s books, old Karl May editions, literature about the colonial wars or the travel adventures of Sven Hedin – went through the antiquarian bookshops, rummaged through the room-high shelves, pulled out this and that book, found often something he wasn’t even looking for. Whether Paris or London, Dublin or New York – antiquarian bookshops were a world apart, just as Virginia Woolf had written it: gathering places for wild, homeless books. What luck when you came across a specimen that you had been looking for for a long time. How would it spoil the fun if everything you’re looking for was freely available in multiple copies to choose from.

But that is exactly what happened with the trade in old books. The internet was invented. The ZVAB, central directory of antiquarian books, enters the stage. Are you looking for “Fire and Sword in Sudan”, by Rudolph Slatin, alias Slatin Pascha, Leipzig 1896, the legendary report of an Austrian officer from the time of the Mahdi uprising in Sudan? In the past, you would have had to comb through dozens of antiquarian bookshops. Today you click on ZVAB and you have 30 offers between 15 and 150 euros. The dealer sits somewhere in the middle of nowhere, he doesn’t need a shop in the big city with horrific rents, he has no expenses, he adds the shipping costs to the price.

He quickly gives up online trading, he wants to see the customer

“It just sucks,” says Rainer Koebelin. He also tried internet trading once, but quickly gave it up again. That’s not what makes him happy about his job. He wants to see the customer, talk to him. “I only have general knowledge about books,” he says, “I learn most of it from my customers.” But today, customers only trickle sparsely into Rainer Köbelin’s antiquarian bookshop on Schellingstrasse. Aside from destroying all the magic of the old book trade, the internet has also thoroughly spoiled the prices. In the past, the price a book fetched at auction provided a reasonably reliable guide. Today, prices on the Internet are completely arbitrary. Recently, says Rainer Koebelin, he googled a title and found prices ranging from 23 to 970 euros – with the same description of the condition. “Today the motto is: cheap, cheap, cheap,” states Köbelin. “If I charge ten euros for a book, the customer says: But that’s 6.50 euros on the Internet.”

The result: the antique shops are dying out. In 1967, when he started, there were eleven antique music shops in Munich alone, he recalls. Today there isn’t a single one. A “Munich antiquarian book guide” from 2011 lists 34 antiquarian shops – if Rainer Köbelin looks at them today, he can delete two out of three – they no longer exist. Luckily he has a good pension and is not economically dependent on the profits from his business. That, he says, would barely cover the rent for the shop. But as long as he can stand tall, he’ll keep going. “There’s not a day that I don’t like going to the store,” he says. “I feel good there. I wouldn’t like to live anywhere without books.”

A customer has entered the store, he looks a little here, a little there. His gaze falls on a stack of delivery booklets from the “Swabian Dictionary”, Tübingen, 1904. “How much do they cost?” “Two euros,” says Rainer Koebelin. “I’ll take three,” the customer decides. He has a friend who is Swabian and is interested in language and dialect. “That’s a great Christmas present,” says the customer.

A small, wild little bird has found a new home.