Behind the story

About returning to the Turkish earthquake zone – and why reporters sometimes cry

© private / star

A year ago, Fabian Huber experienced the hardest days of his reporting life so far at the epicenter of the earthquake in Turkey. Now he has returned there.

It smelled like death outside my makeshift office. I had retreated to write overnight because… star In Hamburg they were expecting my piece from the earthquake zone in Turkey the next morning. Back then, in February 2023, I accompanied a group of German undertakers, one could also say a little more reverently: the rescuers of the dead. In the destroyed city of Kahramanmaraş, they helped to rescue the many deceased from the rubble and prepare them for burial.

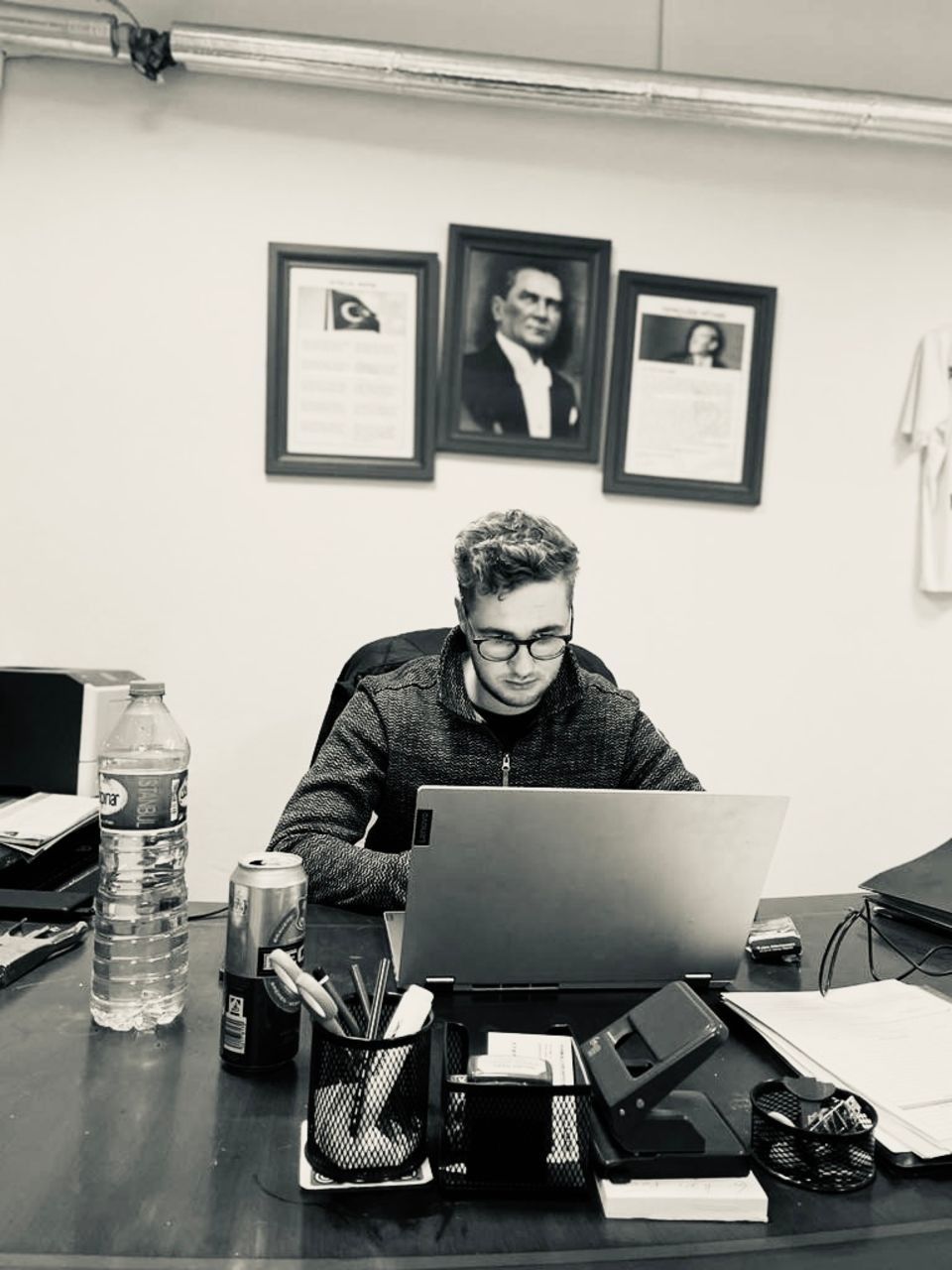

star-Reporter Huber at his writing station in the earthquake area

© Private

I stayed with them in a sports hall with cracks running through the walls, but the authorities confirmed that it was harmless. We slept on cots in the fencers’ room. Shortly beforehand, the dead had been lying on the linoleum floor of the hall. So there I sat, hacking into my laptop. In the nose there is this smell that is commonly described as acrid-sweet-rotten, but which is much worse – and in the head all the depressing scenes of this place.

How I met a woman in front of the remains of a multi-story house, perhaps in her mid-twenties, who held out a pair of toddler shoes to me. They had once been her own. All she had left was that and a wedding album from her buried parents.

How people who had really lost everything – human and material – let me ahead in the soup kitchen queue and gave me cigarettes. Because I am your guest. It made me terribly uncomfortable.

How I looked into a girl’s teary eyes in a tent city for tens of thousands and imagined what might have happened – the siblings dead, the children’s room a pile of rubble made of concrete and plastic? – and how I cried uncontrollably at that moment because all the emotions that had built up inside me over the previous days burst out. It then turned out: The girl was crying because of a broken balloon.

Today, exactly one year later, I can laugh about that moment. But the days in Kahramanmaraş never left my mind. They were the hardest of my reporting life. Maybe not professionally. But human. The full extent of suffering and destruction can hardly be put into words or captured in pictures. It only becomes apparent when you stand in the middle of the rubble.

Too often we don’t return

Back then, I vowed to come back, which isn’t always easy as a journalist: our phone books and contact lists contain so many names and numbers that we take home from trips that it’s impossible to keep in touch with everyone at all times. And yet too often we look away too quickly. Because crises overlap, wars wear out, catastrophes are forgotten.

That’s why I flew back to Kahramanmaraş on the anniversary of the earthquake in Turkey and Syria. For me it was more than just a reporting assignment. It was also a very personal journey. How do you think this city has changed since I was last there?

The gymnasium from back then no longer smells of decay, but of sweat. A handball team now trains there on Tuesday evenings. And otherwise life continues in a dimmed form. I now ate all sorts of lamb offal in restaurants. I bought a Turkish teapot at the bazaar as a souvenir. I slept in a real hotel bed. But when I looked out the window of my room, I still saw a desert of rubble. And that surprised me.

The search for the dead was called off at that time

In February 2023, the help of the German undertakers was abruptly stopped on day 14 after the earthquake. The authorities had ordered to stop the search for the dead. The excavators should no longer dig up the bodies. They should move the rubble out of the city so that reconstruction can begin as quickly as possible. A devastating decision, as many were still looking for their relatives.

But in the twelve months since, hardly anything seems to have happened. Entire streets still resemble a quarry. Tens of thousands of city dwellers who have become homeless no longer have a tarpaulin over their heads, but only a container roof. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government is lagging far behind in building new housing. Kahramanmaraş is still on the ground. Its buildings, its residents.

We spoke to people who are still deprived of sleep by their traumas a year later. With Özmen, 21, who – since he lost his mother in the earthquake – no longer dares to go into multi-storey buildings. With Zekirija, who suddenly dug out a box full of keys from under the counter of his flower shop. They belong to the dead from the collapsed neighboring building. Maybe someone still misses her, he said bitterly. And with Hatun Soya, an old woman in the remote village of Söğütlü.

Her husband and her mother fell victim to the catastrophe, their belongings shattered, all their hopes buried. She talked about her suffering for hours. I felt the pain in her eyes. Then, through tears, she said, “I can’t do this alone.” Back in Germany, I often think of Hatun Soya’s words. When I said goodbye, I promised her that I would come back. Sometime. Hopefully.