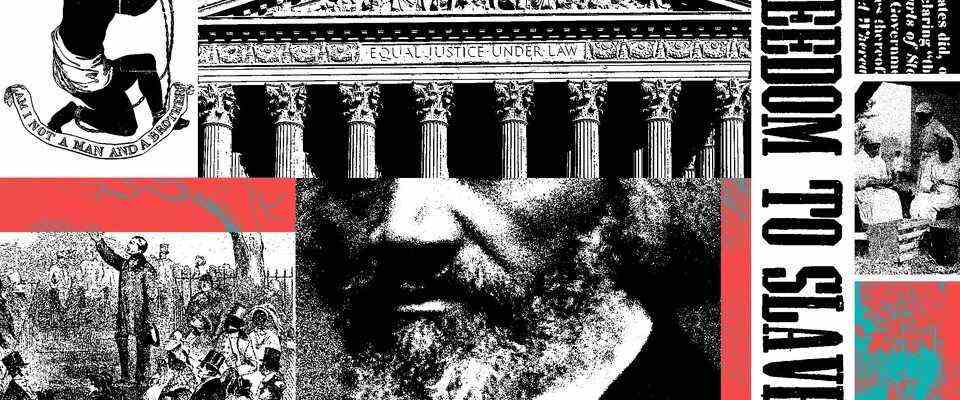

The fault lines of today’s political chasm go back to the decades that preceded the Civil War. One can see them in our geography—most of the states that will recriminalize abortion, for example, are in the old Confederacy and the rural or deindustrialized regions it influenced—and in our racial division, which continues to render the country into, more or less, two camps.

A democratic society might resolve its conflicts by counting heads. But the rigid Constitution, written to protect the regressive elements of the past, still thwarts majority rule. The Senate and the Electoral College favor rural states, often producing minority rule in the Senate and the White House, which together select the Supreme Court. In the House of Representatives, the constitutional provision to count enslaved people as three-fifths of a person long supercharged the power of southern slaveholders; now gerrymandering and voter suppression, left to the unchecked will of state legislatures, thwart the principle of one man, one vote. No wonder the abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison called the founding charter a pact with the devil. When, finally, a serious political force—the Republican Party—arose in the 1850s to address enslavement, the Supreme Court tried to freeze out abolitionism forever with the hateful Dred Scott decision.

Today’s challenges are different—and no offense can be compared with the slavocracy of the antebellum period—but anyone who cares about basic principles of democracy can see that our struggle is much the same. In 2013, the Supreme Court put the Democrats at an enormous disadvantage by gutting the Voting Rights Act and handing back elections to the minority-party-dominated rural-state legislatures. Despite repeated efforts of most of the Democratic senators, Congress has refused to pass a new voting-rights act. In several key states, Republican legislatures have set up new systems that may overturn future election results. Sometime in June, the Supreme Court is likely to rule that American women no longer have a constitutional right to refuse to bear a child, despite the fact that polls regularly show that the overwhelming majority of Americans support some level of abortion rights.

These are dark times, but dark times do not always prevail. Four decades after Black spokesmen told their white so-called friends in the execrable American Colonization Society that they would not be returned to Africa, and just 30-plus years after the Black activist David Walker published an “appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World” promising that “the blacks,” once started, would form a “gang of tigers and lions,” the newborn Republican Party won the presidency on a platform of restricting slavery. Ten years after Garrison torched his copy of the Constitution, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. How did they do it?

The specifics of their fight are not identical to what prodemocracy Americans now face. But the work of the abolitionist movement is comprehensible and replicable. It is the closest thing we have to a blueprint for how to rescue our democracy.

Almost every tactic the mostly white abolitionists used derived from methods that Black organizers tried first. Walker’s appeal, published in 1829, inspired Garrison. There was a Black convention and Lodge movement well before the first white or interracial antislavery society. But one lesson emerges loudly from history: Neither Black nor white Americans could have done it alone.

They made an alliance, and they dug in for the long haul. And they left a playbook.

I. Ideas—and publishing them—matter.

In 1814, The Times of London became the first paper of note to publish off a steam machine, which ran at more than four times the speed of a manual press Less than two decades later, shortly after Garrison started The Liberator in 1831, entrepreneurial types in the antislavery movement decided to use the new technology to cheaply send copies of four antislavery publications to thousands of postal recipients all over the United States. In Georgia, enslavers set the missives on fire.

The obvious comparison is to social media today. Starting, roughly, with the Howard Dean campaign in 2004 and then Barack Obama’s in 2008, the Democrats took an early lead in using the new technology of the day. But antidemocratic forces have been savvy with these tools as well. Equipped since 1998 with a captive cable-television network, Fox News, conservatives moved rapidly during the Obama era to expand into newer social media. Armies of bots, with a complete disregard for fact and extensive funding, helped the right dominate in the all-important arena of political communication; that dominance has only increased since the 2020 election.

The current climate is exhausting, but there is no reason to despair. For most of the abolitionist movement, the publications were few and subscribers scarce. The Liberator depended on the subscriptions of free Black Americans not in need of persuasion. Frederick Douglass’s paper struggled to stay afloat. Most mainstream newspapers were, until the Civil War, hostile to abolition, accurately predicting that it would split the Union. The South persuaded the southern-dominated federal government to close the United States Postal Service to abolitionist literature. But with the development of the telegraph in the 1840s, national newspapers increased their reach and weighed in on the struggle. The activists just kept starting new papers, exploring different approaches and generating content until some things worked.

2. Weekly meetings build solidarity.

Abolitionists quickly realized that they needed to organize in person. They had a model; a generation before, a wave of religious revival, the Second Great Awakening, had swept across the North, leaving a legacy of social activism—and frequent meetings. Garrison’s New England (later Massachusetts) Anti-Slavery Society met regularly for 35 years.

Because there were meetings, the members could take strength from one another’s company. When the societies dispatched speakers far and wide, those speakers had a self-perpetuating takeaway message: Start another society. Because there were meetings, new people could bring new ideas. A couple of years after the New England society’s founding, a woman so beautiful and well dressed that the modest antislavery activists thought she was a spy walked into one such meeting. Let’s have a fashionable bazaar, the socialite Maria Weston Chapman proposed. For a long time, it was the biggest moneymaker abolition had.

The past five years have seen a lot of reform societies: Indivisible, to organize politically across the board; Justice Democrats, to pull the Democratic Party to the left; the Sunrise Movement, to protect the environment. George Floyd’s murder gave new fuel to Black Lives Matter, an older organization. The left would have its own Tea Party, Indivisible proclaimed.

What is now clear is that they are in for not one election cycle but trench warfare. The antislavery societies did not have the good fortune of winning any elections for a long time, so they provide a better model than the Tea Party for how to organize in political trench warfare. Abolition had a primary goal: the immediate end of chattel slavery everywhere in the United States, and its related issue of racial equality. From time to time, other causes surfaced: defiance of the clergy as inadequately opposed to slavery, temperance, women’s suffrage. The most divisive issue turned out to be whether to engage in politics or even violent resistance versus moral suasion and passive nonresistance. The lesson is clear: The branch of abolition that eschewed other causes and narrowly focused on its singular goal won out.

Knowing they were in it for the long haul and that all the institutions of government were arrayed against them, they turned to the only resource that remained: leaving their cozy meetings and organizing the people.

3. Talk and knock, far and wide.

They modeled themselves on the quintessential movement of the disenfranchised—the middle-class British campaign to expand voting rights, which had always been limited to the landed upper classes. The British reformers used petition campaigns, gathering signatures on massive rolls of paper to pressure Parliament to let them in. In 1832, the movement succeeded. And there was a bonus. The moneyed sugar enslavers had been paying off the corrupt landowners who dominated Parliament before the suffrage reform. The newly admitted industrial and urban middle classes, uncorrupted by planter money, immediately formed the backbone of British abolition.

Why can’t we use the petition like that? Garrison asked his right-hand woman, Maria Weston Chapman. Within two years, American women had more than doubled the British numbers in petitions to Congress. The regiments of women walked the sidewalks of small towns all over the North, catching a woman at home and, through her, reaching her male family members. Kitchen-table politics fed the nascent antislavery societies. When the petitions reached Congress, the southerners responded with the gag rule, refusing to accept their own citizens’ pleas. People who didn’t care at all for abolition made alliance with the radicals in defense not of human freedom but of freedom of speech. It was the abolitionists’ first political victory.

Voter registration is the contemporary petition campaign. Last January, a newly enfranchised Black electorate in Georgia helped send two Democrats to the Senate. Because even Black Georgians were formally entitled to vote, and because they were not facing a monolithic two-party system of resistance, the project actually looks easier than the abolitionists’ venture into retail politics in the 1830s. But as the abolitionists learned, touching a new supporter is only the first step. The abolitionists established a lecture corps, the Seventy, and trained its members in preaching abolition to the communities they sought to organize. The Democrats face a worse problem than the abolitionists did, because their opponents are not only trying to govern from above, like the southern enslavers did; they are also playing their own turnout game.

The story of the great petitioner Chapman is also a cautionary tale. In the late 1830s, she followed her purist colleague Garrison into attacking the local churches as inadequately supportive of abolition. She learned a hard lesson about getting ahead of her troops when the more conventional churchgoing women in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society pushed her out. Ultimately, the dynamic of antislavery shifted to the New York–centered antislavery societies run by much more conventional leaders who did not require their members to leave their churches, however imperfect those churches were.

4. Make injustice visible to the public.

By the late 1840s, the little movement had won some elections, and in 1846, one congressman, David Wilmot of Pennsylvania, proposed banning slavery from the new territory conquered in the Mexican War. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina began again to talk of secession. To paper it over, the slave-owning “moderate” Henry Clay proposed a compromise. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 established a system of rendition of fugitive enslaved people from the free states back into the slave states, under the control of the proslavery federal administration and bypassing all protections the free states had thrown up. Northerners were conscripted into helping hunt them down. Within weeks, the streets of Boston and New York were electrified, as long-term residents of these northern cities were dragged in chains back to slavery. Abolitionists gathered to demonstrate everywhere fugitives were being pursued—around courthouses and jails, and in the streets that lined the routes taking them to the docks for their return to slavery. Sometimes the protesters even managed to free or buy out the captives, and when they did, they celebrated.

The return of illegal abortions may offer an opportunity for a return of these sorts of demonstrations. If Roe v. Wade is reversed, a tidal wave of severe restrictions will ensue. States will try to stop delivery of abortion pills into restrictive states and then to stop their citizens from leaving to seek abortions outside their borders. A resistance movement that truly draws from the abolition example will openly defy the state laws, encouraging abortion clinics to operate until patients are dragged, clanking, through the streets of Dallas or Detroit. Mobs of feminists, like the crowds of abolitionists and free Black rescuers did for the fugitives, can fight to defend abortion providers and the people who seek their services.

5. Get control of the Supreme Court.

The prospect of the Court gutting Roe v. Wade and returning women to reproductive conscription in half the states is bad enough, but the current Supreme Court could go far beyond that, overreaching as their predecessors did in 1857. Confronted with Dred Scott, a man whose enslaver had taken him to free territory, seven justices, led by the former slaveholder Chief Justice Roger Taney, ruled that Congress had no power to bar slavery from the territories. Taney thought the preemptive Supreme Court ruling would end the rising sectional tension. Instead, Dred Scott torpedoed the uneasy regional-nonaggression pact. Although the heated rhetoric of nonpersonhood in Taney’s opinion is Dred Scott’s most dramatic legacy, the threat of the slave empire imposing slavery on the rest of the country really fueled the Republican Party’s rise. If the Constitution forbade Congress from excluding slavery from the territories, the same arguments would protect slaveowners’ rights to travel and reside in free states with the people they held. Lemmon v. New York, which raised that very issue, was on its way to the Supreme Court when Lincoln won.

Most white northerners may not have cared that much about the personhood of the “Negro,” as Taney called him, but they cared a lot about what Dred Scott meant for the expansion of slavery to the new territories. White working men of the North considering a move to the frontier surely weren’t going to tolerate competing with the enslaved people brought by their holders there as Dred Scott was maintained, or, worse, see slavery brought into their little towns in upstate New York and New England. When, after Lincoln was elected, the same slavery-loving chief justice ordered the new president to stop protecting the rail yards around Washington, D.C., by arresting Confederate insurgents and spies, Lincoln simply ignored the order. Lincoln took the very public occasion of his first inauguration to warn the Court that it had provoked resistance. If the Court had the last word, the new president announced, “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers,” having handed too much power to unelected justices. After three proslavery Democrats stepped off the Court early in his first term, Lincoln replaced them with antislavery Republicans. The next hot case went for the president, by a vote of 5–4. In 1863, the Republican-led Congress created a Tenth Judicial Circuit to include newly admitted Oregon and, using the enlarged judiciary as an opportunity, it “packed” the Court with a tenth justice.

On January 13, 2022, the Supreme Court struck down President Joe Biden’s program of mandatory vaccines or testing. (The Court narrowly upheld a mandate for the recipients of federal health-care funds.) Soon, the Court is likely to confront the claim that a fetus is a person and thus protected against abortion by the due-process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. As in Lemmon v. New York, a decision to that effect would impose the sexist regime largely centered in the southern and rural states from coast to coast. Will that all-powerful electoral demographic of white suburban women agree once again to fly away, as their mothers once flew to places like Sweden, for their abortions? The liberal movement needs to lay the groundwork so that when conservative overreach comes, it triggers a reaction like the one that greeted Dred Scott. By the time the feckless Chief Justice Taney deployed the unrepresentative power of the Supreme Court to douse abolition politics, the fire was too well laid.

6. Don’t be intimidated.

Like today’s right, supporters of slavery dominated the vigilante landscape during much of abolition. Pistol-wielding southerners in Congress threatening duels often drove abolition-inclined northern congressmen into retirement, lest they have to choose between their honor and their lives. In northern cities, anti-abolitionist mobs were particularly prominent when abolition started to get some traction in the 1830s. The balance of violence began to shift after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was enacted. The crucial change started, as usual, with the Black abolitionist forces, such as vigilance committees, formed to warn fugitives of the prospect of slave catchers. Led by Black leaders of the abolitionist movement, the reluctant followers of passive nonresistance one by one came to accept the need for force, as nonresistance looked more and more like a strategy only white men could afford to indulge. During the campaign of 1860, white forces of antislavery emerged on the street in brigades of caped young male Republicans called “Wide Awakes.” Although not expressly violent, the Wide Awakes adopted elaborate military rhetoric and uniforms and participated eagerly in clashes in places with close races.

By 1860, antislavery forces could see the constitutional order shifting to their side. If the future could be determined by the election rather than by who had the most firepower, they could anticipate victory ahead. On November 6, historians report, the Wide Awakes “policed the polls.” The Confederate states refused to accept the outcome of the election, and bloodshed unknown in America before or since ensued. But as Lincoln said, sorrowfully, in his second inaugural address, on the eve of the Confederate surrender at the Battle of Appomattox Court House, “If God wills that it continue until … every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

After the 2020 presidential election, the right’s vigilantism focused on the certification of the results, and it ultimately failed. The past year has been full of reports of local election officials who have retired rather than face the ongoing threats directed at them. The lesson from 1860 is that ultimately the forces of democratic self-governance must stand up to the vigilantes. Hopefully, law enforcement will play its proper role in keeping order and protecting the democratic process during the fraught years to come. But the hard lesson of abolition is that it never pays to yield to bullies. In The Liberator’s early years, when murderous mobs were a constant threat, Black allies guarded Lloyd Garrison’s journey home from the office. We don’t know if he even knew they were there.

7. Never give up.

This is the most important lesson of all. In 1838, the enslaved Marylander Frederick Bailey donned a nautical outfit and slipped aboard a train headed north, disguised as a free seaman on leave. He drew his first real breath, he later reported, when he reached New York. Just 27 years later, renamed Frederick Douglass, he appeared at the White House, the first Black man to try to attend an inaugural celebration. “Show him in,” President Lincoln told the scandalized guards. “There is no one,” he said to Douglass, “whose opinion means more to me.”