A shock awaited Drake’s fans when they first hit “Play” on his latest album. A gentle instrumental intro lulled the ears for 37 seconds. Then the second track, “Falling Back,” cut in, the audio equivalent of a jump scare in a horror movie. The bigger surprise was this new song’s sound: a beat not built on the woozy, asymmetrical rhythms that characterize much of modern hip-hop and R&B, but rather upon the sort of steady thump that has kept dance floors bustling for decades now.

Drake had dabbled in dance music before, but not like he turned out to do on Honestly, Nevermind. Almost all of its songs channeled house music, the electronic, energetic style that was invented in predominantly Black, gay clubs in 1980s Chicago and that has evolved into countless subgenres since then. In doing so, Drake joined a brewing pop trend. Beyoncé had just promoted her new album, Renaissance, by posing in sequins and with a mirror ball; she soon released an upbeat single, “Break My Soul,” that paid tribute to ’90s house. The Weeknd had kicked off the year with a concept album about endless grooving. Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” had become the latest in a recent wave of Billboard Hot 100 hits featuring arrangements of strutting, steady disco. After years of bummer vibes and trap beats ruling pop, 2022 is shaping up to be the year in which stadium-tier musicians get really into raving.

This trend, though, is already ticking off certain listeners. After Honestly, Nevermind dropped, lots of people expressed mystification on social media that Drake had started making oontz oontz (or untz untz) music. Some listeners joked that the album’s sound reminded them of white girls, gay pride, and Abercrombie & Fitch, comparisons implying that dance music is feminine, embarrassing, generic, and white. The last attribute was particularly odd to see ascribed to an album made by a Black rapper and a number of producers of color, drawing from musical styles invented by Black people.

Drake has never exactly been exempt from public ridicule, but this particular blend of disrespect and confusion has long been part of the story of dance music. In the hours after Honestly, Nevermind was released, the music critic Craig Seymour ignited a mini-controversy by tweeting that the term oontz oontz was a microaggression that derogatorily oversimplifies “complex rhythms with deep African roots.” Thousands of people replied to one of his tweets, many with angry disagreement—which, to Seymour, just proved his point. “A lot of times, when people use terms like [oontz oontz], they are loaded with things like racism and sexism and homophobia,” he said a week later by phone. “And when you call them on it, they just lose their minds.”

His take may sound like an extreme read on a silly onomatopoeia. But club-music history is littered with examples of jokey language that, when inspected, is clearly shaped by prejudice and appropriation: Again and again, the sound of subcultural pleasure gets associated with corniness and Caucasians, leading to mockery that tarnishes the whole scene. In the late ’70s, the “Disco sucks” movement flared around the time when John Travolta became a diverse musical style’s straight-white-male mascot. During the electronica wave of the ’90s and early 2000s, the Black-invented genre of techno became conflated with Moby and then turned into a punch line for Eminem. In the 2010s, the Jamaican-influenced style of dubstep traveled from London dives to Las Vegas mega-clubs, where it was tarred as gaudy brostep.

Dance always survives, regardless of how the public and pop stars treat it at any particular moment. Many members of its vibrant undergrounds, in fact, cherish normie disinterest. But why does music designed for pleasure and release so often get treated as weird? Why does the American mainstream swing so wildly between embracing dance music and despising it? Perhaps, simply, because fun can be a threatening thing. A great dance party encourages participants to forget personal hang-ups and social hierarchies, and respecting the music that invites such liberation means respecting the people for whom a night of escape can be far from frivolous. Seymour told me he doesn’t expect everyone to become experts on, say, the difference between Baltimore and New Jersey club, but he’d prefer if people didn’t demean the producers, DJs, and dancers who do know such things. Dance is “not just here, fun for a moment,” he said. “This is music that sustained some of us for our entire lives.”

The story of club music is a story about a simple impulse expressed in complex ways. “Throughout much of human history, the term ‘dance music’ would have sounded redundant. What else is music for?” the critic Kelefa Sanneh wrote last year in his book Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres. Indeed, people twerk to Cardi B, pogo to Olivia Rodrigo, and shimmy to Bruce Springsteen—why are those artists not considered dance?

One answer is musicological, tracing back to the four-on-the-floor rhythm pioneered by the Philadelphia soul drummer Earl Young in the early 1970s. Another is technological: Disco’s ascent followed the rise of disc jockeys spinning records with an ear toward endless grooving. Dance songs succeed or fail in part based on how well they can be integrated into a set, augmenting without disrupting. This unapologetic utilitarianism can make some people dismiss the music’s artistic value. The dance-music journalist Michaelangelo Matos told me that he has often heard outsiders ask, “Where’s the song?” (meaning, roughly, I can’t sing this in the shower).

Yet dance artists face many of the same imperatives as musicians in any genre: to build and release tension, to convey emotion, and to innovate. The gridlike strictures of a backbeat can enable wild experimentation (listen to the intricate syncopation of drum and bass, which boomed in the ’90s and is now back in fashion) and powerful drama (Seymour considers the house diva Ultra Naté’s heartbroken 1991 debut album, Blue Notes in the Basement, a genre masterpiece). A particular kind of magic, too, can arise through the interplay of artists, DJ, producers, and crowds. Or as Sanneh puts it, “Too often, pop music history is organized around great albums, rather than great parties. Often, that means dance music gets written out.”

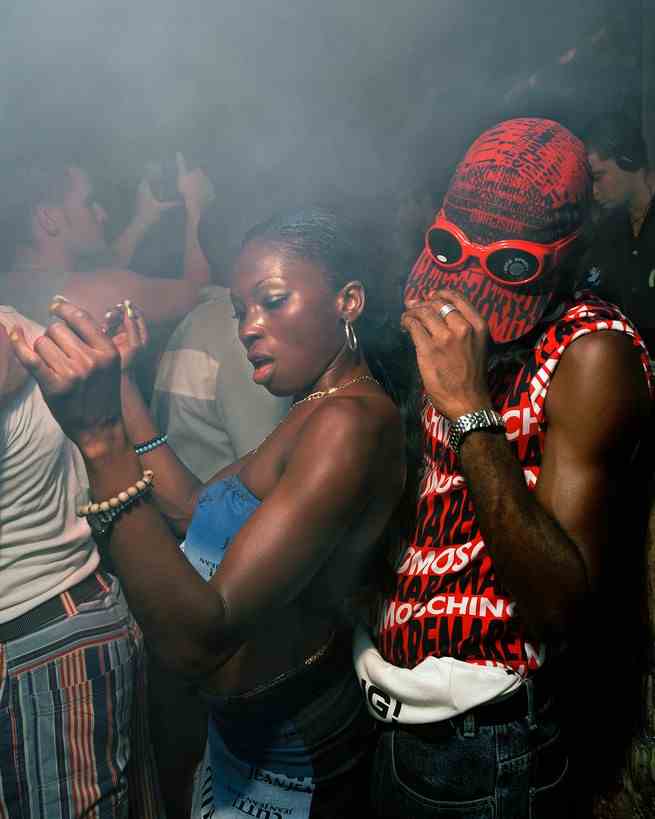

The genre is typically beloved by people in need of great parties: communities on the margins of society, looking for escape and fellowship. Seymour points out that clubbing was basically church for the Black gay men who once danced into the early Sunday hours at Paradise Garage—the New York City venue where the legendary house DJ Larry Levan presided in the late ’70s and ’80s. Many of the revelers had been raised in devoutly Christian families that later rejected them. They came to commune with what was basically a form of gospel music—wailing vocals, intense crescendos—but, crucially, “without feeling judged” for their sexuality, Seymour said.

Such social context tends to get obscured whenever a particular dance-music style moves from the underground to the mainstream—that is, until the backlash comes. Take the story of the “Disco sucks” movement. By 1979, dance music had become associated in the public imagination not only with the Black, brown, and gay communities that had originated it earlier in the decade, but with a dorky brand of whiteness thanks to Saturday Night Fever and the Bee Gees. Professing to hate the genre’s tackiness, the Chicago rock-radio DJ Steve Dahl invited people to bring albums to a baseball stadium for destruction at a “Disco Demolition Night.”

But it wasn’t just “Stayin’ Alive” that got smashed. Vince Lawrence, an usher at the stadium (and who went on to be a house producer), reported seeing lots of non-disco albums—R&B, funk—on the pile, by Black artists. “The message was, If you’re Black or you’re gay, then you’re not one of us,” Lawrence said in a 2018 documentary, referring to the impression he got from the crowd that night. For what it’s worth, Dahl has long rejected claims of his anti-disco campaign being hateful. He has said he was just trying to protect “the Chicago rock’n’roll lifestyle.”

Whatever the stated motives, instances of blowback can have lasting consequences. Though the pop of the ’80s continued to pulse and groove—think about Madonna or new wave—the term disco was “a dirty word,” Matos said. Nile Rodgers, the influential guitarist of the band Chic, took refuge in the U.K. music scene during that decade because of the stigma against dance music in the U.S. Indeed, Europe has long enjoyed a somewhat less-fraught relationship with dance than America has—a fact that, even today, helps define the popular image of electronic music as being white and cosmopolitan. Asked why America tends to resist raving, Matos—whose book The Underground Is Massive is about dance music in the U.S.—was blunt: “It’s a big, macho country full of big, macho men who are afraid of their own shadows, never mind afraid of other men who might love them.”

If fear does indeed form the basis of anxieties about dance music, it is partly a fear of change that is already afoot. Look at the way that Dahl’s rhetoric about defending the “Chicago rock’n’roll lifestyle” now echoes in the hip-hop world’s reaction to Drake’s new album. On his podcast, the commentator Joe Budden asked Vince Staples, “Do you think Drake putting out a dance album gets us closer to the elimination of rap music as a whole?” Interviewed by TMZ, the producer Irv Gotti expressed dismay about Honestly, Nevermind and said he hopes it doesn’t signal “the demise of hip-hop.”

These are striking concerns to hear, given that house music and hip-hop were invented through the same means: underground Black DJs spinning old disco and soul records and creating a new sound. Rap and house, in fact, were once allied, intermixed genres, as seen in the late-’80s wave of “hip-house” songs. But as AIDS tore through the gay communities where house thrived and rappers succeeded by projecting a kind of survivalist machismo, it “ended up creating a very homophobic environment in hip-hop, where anything remotely dance-oriented was to be avoided,” Seymour said. Exceptions cropped up, but the underlying attitudes clearly persisted. Now, on TikTok, many of the jokes about Drake’s new music imply that the rapper has left hip-hop behind for homosexuality, as if the two things are incompatible.

But divisions between dance and hip-hop—and with it, traditionalist attitudes about sex, race, and gender—have been weakening for a while now. For Cakes Da Killa, a 31-year-old queer rapper who has mixed house and hip-hop throughout his career, the hullabaloo around Drake’s album is ridiculous. Growing up in New Jersey, home of the frenetic dance style known as Jersey club, he always realized that house music was part of his heritage. But he said that in the past decade, he and other young artists of color have felt particularly empowered to play with that heritage. “With urban marketing, we’re sold this very monolithic idea of, This is what Black males listen to; this is what Black women listen to,” he said. “We’re slowly realizing that, as the blueprints of a lot of these genres, we’re free to do and listen and create whatever you want.”

Indeed, if the title of Beyoncé’s new album is christening a renaissance in the club, that renaissance has already been under way without the input of pop stars. “Dance music is in really robust shape right now,” Matos told me. “And a lot of that is because of what happened after EDM.” Short for “electronic dance music,” EDM is the walloping, arena-rock-inspired dance sound that made Skrillex and Swedish House Mafia into household names in the early 2010s. EDM was all about scale—big festivals, aggressive bass lines—and it minted masses of new dance-music fans. “I think the EDM wave kind of reintroduced that rave lifestyle to my generation,” Cakes Da Killa said. “You know, the whole concept of doing MDMA and going to Berlin.”

But EDM’s headliners and consumers were overwhelmingly white. Over the course of the 2010s, parts of the dance world—like so many other cultural spheres—underwent a reckoning with racism and whitewashing. “Something that started as gay black/Latino club music is now sold, shuffled and packaged as having very little to do with either,” wrote the Chicago DJ Derrick Carter in a much-quoted Facebook post in 2014. Festivals, organizations, and booking agencies popped up with the expressed goal to, as one apparel brand put it, “Make Techno Black Again.” At the same time, an explosion in queer visibility in the entertainment industry gave house music—the backbeat of the vogue balls and drag pageants that have been the subject of so much recent TV—a wider audience. Seymour cited Kaytranada, Honey Dijon (who is listed in the writer credits for Renaissance), and Black Coffee (a producer on Drake’s recent album) as the sort of room-filling DJs who exemplify this turn.

Given that context, is it any surprise that Black superstars are having house moments? Both Drake and Beyoncé are known for mainstreaming ideas that have been subcultural. Right now, they may be picking up on a simmering and broad interest in dance not just as party music, but also as an artistic lineage with a specific cultural context. Honestly, Nevermind echoes with references to club-music subgenres and scenes present and past. “Break My Soul” both sounds a lot like the Robin S. house classic “Show Me Love” and features that song’s writers in its credits. “Moby could sample some old field records; nobody really cared where they came from—it’s just a funky sound, you know?” Seymour said. “But now [in the general public] I think there’s much more understanding of the history, or at least understanding that there is a history.”

Yet knowing that history means also knowing a history of backlash. “The thing that will kill any sort of revival of dance music will be the same thing that has done it every time,” Seymour said. “It starts with people talking dismissively about it … and then radio no longer wants to be associated … and it just starts to go away.” The solution, as he sees it, is for people to show the common decency that past innovators of the genre were often denied: “Before this thing starts, let’s start respecting it as a form of music, like any other form of music.”