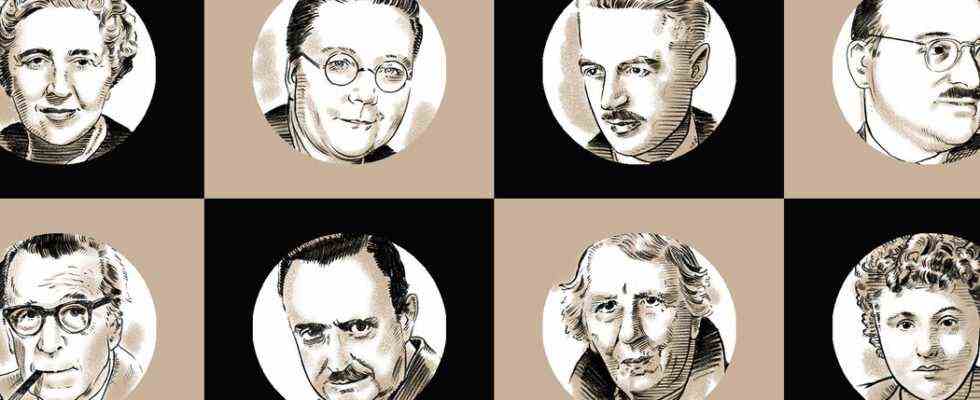

‘The Mysterious Affair at Styles,’ by Agatha Christie

Though this may be the first published book of Miss Agatha Christie, she betrays the cunning of an old hand. She first presents the mysterious affair of Styles and then proceeds to make it more and more mysterious by leading us gently to all sorts of wrong theories about the criminal.

Mrs. Inglethorpe, rich, elderly lady, is found early one morning writhing in pain from the effects, as it is determined later, of poison. She dies with the name of her husband on her lips. This husband (her second) had been her secretary, and was 20 years younger than she. There was “the most awful row” between Mr. and Mrs. Inglethorpe on the day preceding the crime, the same day Mr. Inglethorpe was declared by the village chemist to have bought a bottle of strychnine on the pretext of having to kill a dog.

Mr. Inglethorpe would certainly have been arrested there and then had it not been for a certain delightful little old man, a refugee from Belgium and formerly a famous detective, who took a hand in the case. He prevented the arrest by producing an unimpeachable alibi for Mr. Inglethorpe. But if you think that ends the story you are mistaken. You must wait for the last-but-one chapter for the last link in the chain of evidence that enabled M. Poirot to unravel the whole complicated plot and lay the guilt where it really belonged. And you may safely make a wager with yourself that until you have heard M. Poirot’s final word on the mysterious affair at Styles, you will be kept guessing at the solution and will certainly never lay down this most entertaining book. [Review first published Dec. 26, 1920]

‘Whose Body?’ by Dorothy Sayers

A new member of the extensive and entertaining fellowship of detective story writers, Miss Dorothy L. Sayers presents as her initial offering a very ingenious tale. Its leading character is a certain genial and eccentric Lord Peter Wimsey, younger brother of the Duke of Denver, who has taken up amateur detecting as a pastime. Closely associated with him is a professional from Scotland Yard, Mr. Parker, who does the routine work. Bunter, Lord Peter’s very capable man, is useful in other ways than his avowed duties of valet and butler.

The mystery which engages these three very different persons is a double one. In other words, there are two strange events, and in the beginning there is no apparent connection. The first is the discovery by a timorous and eminently respectable architect of the nude body of a murdered man, neatly disposed in his bathtub, decorated with a pair of gold-rimmed pince-nez. The second is the disappearance of the wealthy financier Sir Reuben Levy, who, his cook testified, had come home at midnight and gone to his room. Before morning he had vanished. But not one stitch of clothing had vanished with him; not even his spectacles, which his nearsightedness made absolutely indispensable. What connection was there between the two events? And whose body was it in the bathtub, since it was very certainly not that of Sir Reuben Levy?

If Miss Sayers can maintain the standard she has set for herself in this tale, there seems to be no reason the discerning, but by no means infallible, Lord Peter should not become one of the best-known and best-liked of the amateur detectives of fiction. [Review first published May 27, 1923]

‘The Maltese Falcon,’ by Dashiell Hammett (Feb. 23, 1930)

If the locution “hard-boiled” had not already been coined it would be necessary to coin it now to describe the characters of Dashiell Hammett’s latest detective story. All the persons of the book are of that description, and the hardest boiled one of the lot is Sam Spade, the private detective, who gives the impression that he is on the side of the law only when it suits. If Spade had a weakness it would be women, but appreciative as he is of their charms, never, even in his most intimate relationships, does he forget to look out for the interests of Samuel Spade. And it is well that he does, for the criminals with whom he comes in contact are almost as hard-boiled as he. Mr. Hammett, we understand, was once a Pinkerton’s operative, and he probably knows there is very little romance about the detective business. There is none of it in his book, but there is plenty of excitement. [Review first published Feb. 23, 1930]

‘The Dutch Shoe Mystery,’ by Ellery Queen

Miss Abigail Doorn, founder and patron of the Dutch Memorial Hospital, had been seriously injured when she fell down a flight of stairs. Dr. Janney, a weird little surgical wizard, directed that an immediate operation be performed. Ellery Queen, one of our most intelligent and logical detectives, happened to be visiting the hospital and had been invited to witness the operation. When Miss Doorn, with much clinical detail, is wheeled into the amphitheater, it is discovered that she has been strangled. The strands of the story are further tangled when Dr. Janney is also killed. Queen, aided by his father, sets out to ascertain who it was that impersonated Dr. Janney when Miss Doorn was slain. It was someone who knew every mannerism of the little surgeon, walked boldly into an antechamber off the operating theater and, while a nurse made the last preparations, fixed a fine wire about the old woman’s neck. The book is thoroughly engrossing. — Bruce Nae [Review first published Oct. 4, 1931]

Explore the New York Times Book Review

Want to keep up with the latest and greatest in books? This is a good place to start.

‘The Crossroad Murders,’ by Georges Simenon

A black monocle which conceals a glass eye is the distinguishing feature of a man who is first suspected of murder at the crossroad of the Three Widows, but the severest grilling of which Inspector Maigret and his colleagues of the Judiciary Police are capable fails to break the man down. Further investigation at the scene of the crime puts Maigret in possession of various bits of information which, when fitted together, provide the solution of a puzzle whose component parts appear at first glance to be utterly incongruous. Compared with the general run of detective novels, this one is relatively short, but the reader need not feel cheated. Georges Simenon has the happy faculty of being able to pack large gobs of mystery and excitement into a small number of pages. Brevity is not, after all, an unpardonable sin. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published Feb. 5, 1933]

‘Hag’s Nook,’ by John Dickson Carr

A curse hangs over the Starberths, dating from the time when two generations of the family were governors of Chatterham Prison. Tradition has it that one male each generation dies of a broken neck. The prison, now in ruins, stands near the family home, and the eldest son in each generation must, on the night of his 25th birthday, go alone to the prison, enter the governor’s room, open the ancient safe and learn the family secret. Should he fail to do this, he forfeits his title to the estate.

As our story opens, young Martin Starberth is about to undergo this ordeal. Martin dies in the manner ordained, but Dr. Fell, a friend of the family, is skeptical about family curses and takes charge of the investigation. Aside from being a remarkably good detective, the learned doctor is a lexicographer and expert on drinking songs and drinking customs, past and present. Skoal, and likewise prosit, Dr. Fell. And here’s looking at Mr. Carr, who has written a clever yarn. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published April 16, 1933]

‘The Saltmarsh Murders,’ by Gladys Mitchell

Not often has an odder set of characters been gathered together than those who appear in the pages of this book, and the woman psychoanalyst who plays the detective role is the oddest of the lot. Her methods are utterly unorthodox and extremely confusing, but she succeeds where others fail in ferreting out the baffling crimes. The story is told by Noel Wells, a young curate who assists Mrs. Bradley, the psychoanalyst, in her investigations without any but the faintest understanding of what she is up to. His suspicions, as well as those of the reader, are directed toward one after another of the various characters, but he is kept completely in the dark as to Mrs. Bradley’s own theories. This book, we understand, is Gladys Mitchell’s first introduction to American readers. It reveals her as adept in the delineation of eccentric characters and the possessor of a keen sense of humor as well as the ability to concoct a puzzling mystery yarn. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published April 30, 1933]

‘The Death of a Ghost,’ by Margery Allingham

The identity of the murderer in this story does not long remain a secret. The police know, and so does Albert Campion, the brilliant amateur who has appeared in other stories by Margery Allingham. The difficulty is to prove anything, for the murders have been so ingeniously planned and executed that there is not a shred of evidence that would have the slightest weight in court. The only thing to do is play a waiting game in the hope that the murderer may attempt another killing and be caught in the act. The next attempt is so nearly successful that the inspector says to the intended victim, “If you ever get nearer to Death than you were last night you’ll be able to steal his scythe.”

The setting for this mystery is so nearly perfect that one is tempted to say that it is more important than the mystery itself. It is the one setting in which such a story could be placed — the artistic world of London and, more specifically, the studio of John Lafcadio, who died 20 years before the story opens after making a will that is the direct cause of the tragedies to come. The personality of Lafcadio dominates the narrative through his widow, his granddaughter, and other members of his household. All these characters are interesting for their own sakes as well as for the light they cast on the man they all revered and loved. Particularly is this true of Belle Lafcadio, the widow, one of the most delightful old ladies we have ever encountered in or out of books.

Margery Allingham has written some unusually good detective stories before now, but in this one she has quite surpassed herself. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published April 15, 1934]

‘The Kidnap Murder Case,’ by S.S. Van Dine

Save for a brief dissertation on semiprecious stones, Philo Vance displays little of his encyclopedic learning in this book, but to make up for this he has added a new accomplishment which may endear him to those readers who have regarded him as too highbrow to be a real he-man. Vance now reveals himself as a gunfighter who can pump hot lead with the best of them. For the rest, he is the same old Philo Vance, distinguished for his keen observation of details that escape the notice of Sergeant Heath and his minions, and for his adroit questioning of witnesses and suspects.

The shooting takes place near the end of the story, when Philo Vance is in search of evidence to support the theory that he has already evolved concerning the kidnapping and murder of Kaspar Kenting. Three extremely undesirable citizens bite the dust before the scene is over, but there remains one more to be disposed of in the last chapter.

“The Kidnap Murder Case” is real, simon-pure Van Dine, and that should be good enough for anybody. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published Oct. 18, 1936]

‘They Found Him Dead,’ by Georgette Heyer

There are not so many shudders in Georgette Heyer’s murder mysteries as there are in those of some other writers, but there is a lot more fun. In this book she has created a most amusing group of characters, from the old grandmother who is able to hear perfectly well if only people wouldn’t mutter at her, down to the 15-year-old boy who loves American gangster films and who fairly wallows in crime, even though he does turn rather white around the gills when he sees a corpse. He wants to help the detectives, and he gets in their way so much that they finally give him the job of shadowing the butler. The boy doesn’t know that butlers are never guilty. It’s against the rules laid down by experts in detective fiction.

Many of the characters in this story are related, and the reader may find some difficulty in telling them apart. Foreseeing this difficulty, Miss Heyer has written a jacket blurb which no one should miss reading. In it she gives brief character sketches of each of the more important figures in the book and reveals just enough of the plot to whet the appetite. This blurb is like a cocktail before a feast; it makes you want more cocktails, but you don’t really need them, for there is nothing dry about the repast of which you are about to partake. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published Aug. 8, 1937]

‘The Secret Vanguard,’ by Michael Innes

Why should anyone want to murder a harmless minor poet who writes of buttercups and daisies and the delights of rural life? John Appleby of Scotland Yard wonders about that and communicates his puzzlement to Mr. Hetherton, an archaeologist whose thoughts seldom stray from his chosen field. On this occasion they do stray, and Mr. Hetherton turns out to be of considerable help to Appleby in solving the puzzle. The second important development in this case is the kidnapping of a young woman on her way to Scotland, not long after she has heard a man misquote Swinburne. Can that be why it has become necessary to spirit her away?

Sheila’s escape from her captors and her part in the final episode make a story that bears comparison with John Buchan’s novels of adventure and international intrigue, not because of any similarity of plot, but because Innes, like Buchan, has mastered the art of swift, exciting and well-organized narrative. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published Jan. 12, 1941]

‘Death and the Dancing Footman,’ by Ngaio Marsh

The new footman lingered in the empty hall, when a blast of melody preceded the news broadcast, and did a few steps to “Boomps-a-Daisy.” So he became a maker and breaker of alibis when murder brought a climax to Jonathan Royal’s house party: a house party whose hostilities made its chief charm for the host’s wry sense of fun. Since this is Ngaio Marsh’s latest mystery, no one needs to be told with what skill its diverse personalities are set to confront each other, or how cleverly events and people interact.

Royal’s mischief-making centered around his neighbor Sandra Compline and her two sons: a once beautiful woman with a tragic disfigurement, the quiet but oddly subtle heir whom she neglected and the dashing young cad whom she adored; also the girl they had loved and the woman with whom the younger was flirting. It was cruel to bring them all together. Before the game was played out one was dead by murder and another by suicide at Royal’s stormbound country place.

Although the puzzle is intricate, the appeal of “Death and the Dancing Footman” is almost as much that of a novel as of a murder mystery. The movement of the plot is deliberate at the beginning and rather arbitrarily slowed down at the end. But the interest of character is brilliant and unflagging, and both incident and conversation are alive with wit. — Kay Irvin [Review first published Sept. 14, 1941]

‘The Devil Loves Me,’ by Margaret Millar

Some of the characters in this book belong in a psychopathic ward, some in an alcoholic ward, and some would be at home in either. Since the unofficial detective on the case is Dr. Paul Frye, psychiatrist, this is all to the good. The story opens with Frye waiting at church, about to be married. The wedding is postponed because of the sudden illness of one of the bridesmaids, who turns out to have been poisoned. The bridesmaid recovers, but her brother turns up dead early the next morning. It is not poison this time, just a plain head-bashing. Two more murders follow in quick succession, and Dr. Frye and Inspector Sands of the police department have a busy time trying to figure out who did the killing and why. The eccentricities of the various persons make their task exceedingly difficult, and they also add to the entertainment. — Isaac Anderson [Review first published Aug. 16, 1942]