At one point in the long-awaited new film Candyman, billed as a “spiritual sequel” to the 1992 cult horror flick by the same name, a character is heading toward an inevitable confrontation with the monster. We’ve seen this moment a thousand times. The character knows now that evil is afoot. She knows that it’s of a supernatural variety. Blood has been shed. Her every step is measured and cautious. We can hear the creaking. We are tensed, ready for the jump scare. She comes upon a door, slowly opens it. On the other side is a long stairwell leading down to an eerie cellar. We know that she must go down there. She knows that she must go down there. She considers the dark path before her for a moment before gently but decisively shutting the door.

“Nope,” she says.

Watching a screener, I imagined audiences losing it at this particular moment. How many times have we watched horror films in which the protagonist makes the inexplicable choice to go further into danger just to find out what’s down there? For Black viewers, this habit is racialized: This is white-people shit, the joke goes. They obviously don’t have enough to be afraid of in real life, so they go around looking for dangerous situations, opening the door, releasing the curse, unsealing the tomb. There’s a reason “Fuck around and find out” and its cousin, “Play stupid games, win stupid prizes,” are Black proverbs. The protagonist and the creators of the new Candyman—co-written by Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld, and Nia DaCosta, who also directs—are not here to play stupid games.

The original Candyman, an adaptation by the British filmmaker Bernard Rose of the British writer Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden,” was explicitly conceived and directed through a white gaze. The new Candyman is the first horror feature distributed by a major studio to be directed by a Black woman, DaCosta. During the making of it, she was intensely conscious that Black pain has always been a lucrative source of content for Hollywood but is rarely handled with enough consideration to keep it from effectively and constantly re-traumatizing Black viewers. “My concern is really getting into what the film is about and who the film is for,” she told me via email. “With a film like this, that traffics in Black pain and trauma, it’s imperative that it is told from a Black POV; it’s imperative that we consider the audience for whom this film could be harmful, and that we are very careful about execution.”

DaCosta and her collaborators had their work cut out for them. In the original Candyman, Rose imports Barker’s tour de force of mood and shiver—a story that works as both a chiller and a meditation on class in Barker’s native Liverpool—to America, swapping in race for class. In the short story, a white academic traipses into the “drear canyons” of council housing to study graffiti, and residents there begin to tell her tales of horror that they say no one else has believed. In Rose’s film, a white academic traipses into Chicago’s Cabrini-Green projects, where Black families report being terrorized by a Black serial killer who returns from the dead when his name—Candyman (he comes bearing candy)—is invoked five times in front of a mirror. Racially speaking, the results can most generously be described as cringeworthy.

The projects in Rose’s Candyman are an apocalypse, home to an egregious liberal fantasy of an oppressed and impoverished underclass. Kindhearted single mothers who work low-wage jobs deliver monologues in a theatrical Ebonics. Orphaned children roam the streets. The mass of Black families is treated as a nameless, faceless, childish people prone to superstitions and living under the shadow of an unforgiving god. The film offers up a racialized poverty Kabuki in which pain is the chief characteristic of Blackness. It doesn’t help that the imagined backstory for Candyman, dreamed up by Rose, is that he was violently murdered for lusting after a white woman, as if even in our victimization, proximity to whiteness remains a forbidden prize.

The irony, of course, is that the film makes a half-hearted attempt to castigate its protagonist for approaching Blackness in precisely this way. The character of the white academic, named Helen Lyle and played by Virginia Madsen, is a proto-Karen, motivated by righteous feminism and yet completely willing to exploit Black trauma as a tool for personal and career advancement. The film comments on this, only to follow suit; it knowingly nods to Lyle’s racist voyeurism, all the while indulging it. Such was the state of racial politics in the ’90s, when white people felt that all a work needed to qualify as progressive was one Black character with a college degree, in this case Lyle’s best friend and fellow graduate student, Bernie Walsh, played by Kasi Lemmons. (She hangs back when Lyle, flaunting her arrogant bravery, steps through a hole in a crumbling apartment wall: Nope, says Walsh, which doesn’t mean that she makes it to the end.)

I hadn’t seen the original Candyman since I was about 17 years old, and rewatching it, I was struck not only by the absurd and condescending treatment of Black people but, more frighteningly, by how easily I had overlooked this treatment when I was younger and more impressionable—how readily I had accepted that this was just how Black people were portrayed in films. The movies and shows I watched as a kid had thoroughly trained me to see Blackness through the dehumanizing and exploitative lens that white filmmakers applied to it.

In much of the fare I grew up on, that filter meant that Black characters were either throwaway figures or people who had no identity outside of poverty and struggle. Today such racist notions have become more nuanced, but they still serve as a fairly sure guide to which Black screen ventures get produced and how they are developed and marketed. The popular liberal vision of the Black experience is that it is centered on pain—the enduring of it, the overcoming of it—which translates into an endless appetite and funding stream for films and series devoted to the suffering of Black people. The result for me is that my pain and the pain of people I love is endlessly and cruelly capitalized on.

Horror Noire, the 2019 documentary on Black horror based on Robin R. Means Coleman’s book of the same title, proposes that one of the first mainstream films in the genre was not billed as one. D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, released in 1915, dramatizes the heroic—in its view—formation of the Ku Klux Klan, which rides to the rescue of white people everywhere when a libidinous Black man named Gus (portrayed in blackface) assaults a fragile white woman. If horror plays on the audience’s fears as a means of entertainment, The Birth of a Nation would have done so in entirely opposite ways for the country’s Black and white viewers. For white people, the character of Gus functioned as something like a predecessor to Jason Voorhees in Friday the 13th and Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street, an unrepentant monster who is coming for you and all that you love unless he is stopped. The film depicts the ultimate lynching of Gus as a valiant and noble act. Shortly after its release, the movie was screened at the White House for President Woodrow Wilson and his Cabinet. The Birth of a Nation is still considered path-breaking, one of the most important films in early American cinema. Therein lies the horror for the country’s Black population.

Over the next half century, if horror movies had Black characters, we were often comic relief, there to perform racist punch lines as petrified servants or ludicrously startled groundskeepers. Not until 1968 did a Black person feature as the lead in a commercially successful horror film. That year saw the theatrical release of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. The movie, shot in stark black-and-white, is about a motley group of Pennsylvanians who are hunkered down in an abandoned farmhouse fighting off an invasion of cannibalistic zombies. Their leader is a stalwart, practical man named Ben, who takes control of the situation and cares fiercely for the assembled group. Ben is played by Duane Jones, who is thought to be one of the first Black actors in the history of American cinema chosen for a leading role that wasn’t explicitly created to be filled by a Black person. Romero maintained until his death that Jones’s casting was not meant as a political statement but happened simply because he gave the best audition.

Nevertheless, Jones playing Ben in the role of champion helped elevate the film, which would have stood on its own merits as an ensemble disaster flick, into a sharp political allegory. Ben’s chief antagonist inside the house is the small-minded Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), a white man who connives to hoard resources for his family and dethrone Ben. The anxieties of a white middle class resisting integration and Black empowerment are easy to read into his character. “We luck into a safe place,” Cooper yells at Ben, “and you’re telling us we gotta risk our lives just because somebody might need help?” The closest the script comes to directly addressing the racial aspects of the power struggle between the two men is when Ben asserts himself in an oft-quoted scene. “Now get the hell down in the cellar. You can be the boss down there,” he hollers at Cooper. “I’m boss up here.”

For Black people in the ’60s, as militant opposition to the specter of white supremacy inexorably formed, Ben’s words spoke powerful truth. The film is rife with images recalling real-life horrors that Black people faced. Armed rural citizens, all white, assemble to fight off the zombie hordes and remind us of roving gangs of white men who terrorized Black communities. Nighttime fire scenes with torches evoke Klan rallies. And in the film’s most direct allusion to violent reality, after Ben fights off all the zombies and emerges as the only survivor, he is killed in the final scene by local police, who throw his body on a bonfire like so much trash. (In the final scene of his directorial debut, Get Out, Peele provides a satisfyingly flipped version of that memorable close.) Assuming that Jones’s casting was indeed sheer coincidence, Romero’s film highlights another truth about horror in American cinema: The most terrifying things that Romero dreamed up happened to look exactly like the things that Black people confront. And yet the film was not written about race. It is about people fighting off flesh-eating monsters, and doing so in an intensely racialized society.

Among the many reasons I love Night of the Living Dead is that it is a rare case study in the ways a white lens can treat a Black character as a Black human being without lapsing into either racist tropes or dismissive color blindness. I have in mind a Pat Parker poem called “For the white person who wants to know how to be my friend.” “The first thing you do is to forget that i’m Black,” Parker tells the reader. “Second, you must never forget that i’m Black.” The fact that Parker sets out an impossible pair of instructions is not quite the point; the instructions, contradictory though they seem, function as commentary. They are also delivered clearly and in good faith. To treat Black people as humans under the circumstances of our collective social and political oppression requires white people to strike this seemingly impossible balance, which explains why so many of them are so bad at it. My experience is that most white people I’ve met do these two things at precisely the wrong times. They obsess over, fetishize, and exploit my Blackness when the situation does not call for it, and they forget that my Blackness matters precisely when it matters most. I don’t hold out much hope at this point; I’m nearly 47 years old. But when someone, anyone, treats me correctly as a human being, and also as a Black human being, the relief is tremendous.

How Romero managed this remains a mystery to me. Perhaps growing up in a diverse neighborhood helped, or having produced short segments for Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, a show with a legendarily humane perspective on race. Maybe he was just largely immune to the racist assumptions of the time. Whatever accounts for his feat, the film’s arrival in theaters in 1968, a pivotal moment in America’s racial history, bolstered the cultural impact of Night of the Living Dead. The preceding year is often remembered for the Summer of Love, but it was also the year when scores of racial uprisings took place across the country, leading to U.S. military deployment in Detroit. More than 80 people died in the racial violence.

Romero recalled that he was in the car driving to New York to show the film to potential distributors when Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination was announced on the radio. Racial reckoning, the remarkably empty phrase of 2020–21, may not have been in the air then, but amid the outpouring of racialized news, it could have been. Part of what gives Romero’s film its enduring power is the way it speaks to these issues without obsessing over them. Whether or not you believe Romero’s tale of color-blind casting (I’m not sure I do), he succeeded in making a work that allows race to exist fully within the universe of his film rather than using it as a pretext to project white fantasies. The film forgets that Duane Jones is Black, but never allows the viewers to do so.

Such relatively insightful treatment of Black characters was still a rarity, though, and the ’70s saw Black filmmakers forging their own path, starting with, some would argue, the 1971 blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. A new wave of directors sought to integrate a Black Power worldview into cinema to counter decades of stock portrayals of Black people as mammies, butlers, and other servile individuals lacking any semblance of interiority. Working in a variety of genres—comedy, horror, crime, noir—the films shared the goals of homing in on Black communities, featuring Black protagonists and antagonists, and usually foregrounding a struggle against some form of collective racial oppression.

By now, blaxploitation themes and conventions have been so assiduously recycled and referenced by white filmmakers that the cartoonish aspects of the form—preposterous fight sequences, gratuitous sex scenes, pistols hidden in Afros—have eclipsed its contribution to American cinema at the time. Blacula, released in 1972, can be considered the first blaxploitation horror film to carry forward the genre’s defining focus on the quest for Black self-determination: The story begins with a Nigerian prince asking Count Dracula to help stop the slave trade. Dracula refuses, transforming the prince into a vampire and then locking him in a coffin. But 1973’s Ganja & Hess, written and directed by Bill Gunn, is the complex and beautiful high point of Black-directed horror in its early phase.

The film, lumped in with blaxploitation only because no other category exists for 1970s Black cinema, stars Duane Jones as Hess, an isolated, wealthy archaeologist who is stabbed by an unstable assistant (played, in a truly mesmerizing performance, by Gunn himself). The weapon is an ancient dagger that turns him into a vampire. The assistant commits suicide, and Hess is imprisoned in an undead fate, a reclusive and forsaken figure. When the assistant’s wife, Ganja (Marlene Clark), arrives looking for her (now dead) husband, she and Hess fall in love, and she chooses to submit to vampirism partially as a way of outmaneuvering the demons of her own past. “It was as though I was a disease,” she recalls of her childhood abuse at the hands of her mother, “and I think that day I decided that I was a disease, and I was going to give her a full case of it.”

The vampire life proves exquisite, and also grim and lonely, for the couple trying desperately to maintain a hold on their love. Hess ultimately decides to repent for his sins, but Ganja refuses to go back to the mortal world. The film uses vampirism as a metaphor for any number of problems that Black Americans faced—addiction, assimilation, brutal casualty rates in Vietnam—and is surreal, thoughtful, gorgeous, and at times delightfully deranged. Watching it, I found myself transported to a dreamlike state that mirrored the film’s disjointed translucence: Like Ganja, I was desperately willing to be sucked into Gunn’s abstruse and gossamer vision, a welcome relief from the assault that mainstream films often conduct on Blackness.

Despite a screening during critics’ week at Cannes in 1973, Ganja & Hess was not widely seen by American audiences at the time. Its producers, Kelly-Jordan Enterprises, were so displeased by the art-house direction of Gunn’s final product that they halted distribution and sold it to another production company, Heritage Enterprises, which hastily recut it into a lame and nonsensical flick, Blood Couple, that Gunn disavowed. In short, Gunn’s original cut of Ganja & Hess didn’t do enough exploiting to ride the wave of blaxploitation.

During the ’90s, filmmakers who had grown up on blaxploitation began developing their own projects, seeking to move beyond the form’s predictable plots and stereotypical figures while still addressing Black realities for the enjoyment of Black audiences. In the horror genre, Kasi Lemmons’s 1997 work, Eve’s Bayou, stands out for me as among the most expertly crafted and meaningful films of the decade—and as, at least in part, a personal corrective to the original Candyman, in which Lemmons’s character is slain halfway through. In Eve’s Bayou, all of the Black women survive. The film is told from the point of view of Eve, an adult woman recalling her mysterious role, as a 10-year-old (Jurnee Smollett), in the death of her philandering and abusive father (Samuel L. Jackson). The catalytic incident of abuse is refracted intricately through multiple perspectives: Is it real or is it imagined? Does it matter? With its southern-gothic aura and its centering of Black female relationships, Lemmons’s debut effort feels more like a descendant of the work of Julie Dash (whose Daughters of the Dust in 1991 was the first feature by a Black woman to receive a nationwide release) than of anything from the urban horror stream. For me, the joy in watching Lemmons’s work lies somewhere beyond her cinematic achievements, in the nearly spiritual level of care she takes with our relationships and trauma.

Hollywood continued to mine the Black-film revival of the ’90s, pasting its elements (and sometimes its actors) into white films, but not until Peele’s Get Out, in 2017, did a Black horror film made for Black audiences enjoy such widespread popularity. A multilayered film, Get Out is race horror (as opposed to horror happening in a racialized world) and directly uses white racism (particularly the liberal variant) as the primary horror element. The twist is that the film allows its Black characters a hitherto rare level of both agency and redemption. Get Out’s stunning cultural and financial success—it has grossed $255.4 million to date against a $4.5 million budget (principal shooting took a mere 23 days)—predictably sent the industry scrambling after any script that turned Black trauma into genre-film fodder.

We currently find ourselves amid a deluge of projects—Lovecraft Country, Them, Queen & Slim, Antebellum, and others—that leverage, with varying degrees of success, Black pain for drama and entertainment value, at precisely the moment when Black trauma is proving among the most popular forms of non-Hollywood spectacle. Video of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis was viewed by enough people that it prompted as many as 26 million protesters to take to the streets in the U.S. in June 2020. And more than 23 million Americans watched the reading of the verdict in the Derek Chauvin trial, which exceeds the number that tuned in to the Tokyo Olympics’ opening ceremony.

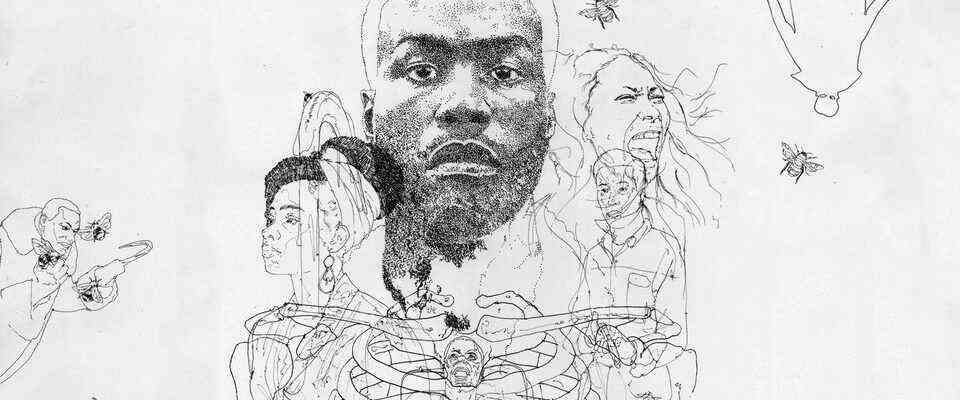

Nia DaCosta’s Candyman, too, probes Black trauma as a source of dread, but its approach is infinitely more informed and nuanced than the perspective that guides the original film. Set in the present day, the story plays out on the former site of the Cabrini-Green housing projects that served as the ghoulish setting for Rose’s film. Those towers have been torn down, the neighborhood thoroughly gentrified. Living in a luxurious condo that now dominates the site are a Black painter, Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), and his girlfriend, Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris), an ambitious gallery director. Both are navigating the thorny terrain that comes with selling Black art to white buyers, and in an adroit bit of self-referencing on the filmmakers’ part, McCoy is frustrated by the callous appetite for Black pain, an experience to which I suspect any Black creative working in 2021 can easily relate.

He finds himself uninspired and resentful, at an artistic dead end. That is, he’s blocked until he learns, at a swank dinner party, about the urban mythology of the Candyman, an undead serial killer who murdered people in the projects—including the white graduate student Helen Lyle, the protagonist in the first Candyman. A terrifying obsession grips him. He pursues the story to its source, dreadfully transforming both his art and himself in the process, and he is drawn into the clutches of the feared mythical slasher. His girlfriend, in the role of a rare Black “final girl” (that horror-film figure who lives to confront the killer at the end), is forced to venture into the catacombs in order to save him, confronting her own personal demons along the way.

DaCosta’s film acutely acknowledges the role that racism plays in the lives of its characters, expertly interweaving it into their motivations for chasing the monstrosity in the first place. McCoy is deeply ambivalent about turning Black horror into grist for sale to white audiences. Cartwright must keep a certain distance from the emotional realities of racism in order to do her job and rise in the art world. She has a big stake in her boyfriend not falling apart, so she avoids acknowledging his unraveling for far too long; her delay leaves time for the monster to do more damage. Ultimately, DaCosta’s Candyman character becomes a cipher that the film’s characters, and by extension its audience, have no choice but to live with—the absence upon which anything can be projected, bequeathed by centuries of Black trauma. This is perhaps where the film hews most faithfully to the Clive Barker short story upon which it is based. “I am rumor,” his monster reminds his victim, and us, in “The Forbidden.” “It’s a blessed condition, believe me. To live in people’s dreams; to be whispered at street corners; but not have to be. Do you understand?”

Happy endings (or at least efforts to grasp at happiness) are of course the most persistent myth of American cinema, and the original Candyman ends the way most horror movies do—with one survivor, in this case a lone infant child, who was kidnapped by the monster and is rescued by Helen Lyle. Lyle herself dies in saving the baby, and in the final twist, her story becomes part of the urban lore that she was studying. When I would watch horror movies growing up, what always struck me about the final scenes was the obvious fate that awaited the survivor: The person who weathered the attack of the undead—the figure who, covered in blood, lived to see the sunrise—would be phenomenally and permanently scarred. I would think about how that person had seen friends and loved ones impaled, dismembered, beheaded; how the survivor would be unable to form healthy relationships, would suffer from phobias and anxieties; how, for the one who lived on, the nightmare would continue forever.

Perhaps I thought about this because even as a child I felt like a survivor of my own horrors, the horrors of this country, its history, its disfigurement of my soul and spirit, and of the souls and spirits of my family, my community, the people I loved. Maybe I was haunted because even as a child I knew that once you have survived horrors, you are never, ever free of them. There is no happy ending. To tell an honest tale of horror, one that acknowledges the humanity of its subjects, is to acknowledge this fact. This is where DaCosta’s Candyman begins, and by recognizing fully and truthfully what it means to have survived what Black people have had to survive, she has made a work in which, for just a few moments, I feel the rare and life-changing experience of being seen by a film and maybe even loved.

This article appears in the October 2021 print edition with the headline “Don’t Go in the Basement.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

.