Isn’t it time Washington embraces a new, more inclusive model?

“From around the world, they come to the halls of power in Washington seeking one thing: a commitment from the American government to protect their countries in a time of rising geopolitical crises,” The New York Times observed on October 27. “In recent months, leaders and diplomats from a growing number of nations have signed security pacts with the United States [or] upgraded military ties and weapons purchases.” Indeed, it is true that the Biden administration helped engineer Finland’s membership in NATO and has boosted its arms exports to its allies in Europe and Asia, as the Times reported. But does any of this translate into greater US influence and prestige in the world? Hardly. Alienated by what is perceived as growing US arrogance and hypocrisy, an ever-larger share of the non-Western world is seeking alternatives to the US-dominated “rules-based international order,” one more attuned to the needs and ambitions of the Global South. Unless Washington finds a way to embrace these aspirations in a constructive fashion, it will soon find itself shunned by much of the world, or overtaken by more adept rivals, such as India and China.

For the most part, US leaders view the Global South as an afterthought in international relations—as an area to consider only when problems in Europe and Westernized Asia have been thoroughly resolved—or as a secondary arena for geopolitical competition with China and Russia. As that competition has gained steam in recent years, Washington has belatedly recognized that it must devote greater attention to the developing world if it is not to be overtaken by its principal rivals. “[We] need to up our game and offer the world, especially the Global South, a better value proposition,” is the cynical guidance offered by Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, in a recent Foreign Affairs article. But treating the developing world as a secondary arena in which to counter China and Russia is not the same thing as addressing the legitimate claims and expectations of the Global South.

The developing world’s demands for a greater say in the management of global affairs have been gaining momentum for some time. In 2009, for example, four major non-Western countries—Brazil, China, India, and Russia (collectively, the BRICs)—agreed to meet on a regular basis and devise plans for accelerated “South-South” economic cooperation and a more egalitarian, less US-dominated world economy. (South Africa later joined the group, formalizing it as the BRICS.) For Washington, however, the most pressing challenge of our time has not been underdevelopment and political marginalization in the Global South, but rather countering the threat to US dominance posed by a rising China. Hence, the voices of the BRICS and other such entities have largely gone unheeded, while the US leaders focused on assembling a coalition of like-minded states to contain China.

The Rise and Fall of the “Rules-Based Order”

Until fairly recently, US policy toward China was aimed not at containing its rise but at managing Beijing’s integration into the existing, US-dominated world economic order. This was the reasoning behind China’s inclusion in the World Trade Organization and other moves aimed at enhancing US-China relations. By the time Donald Trump became president, however, US foreign policy elites had become fearful of China’s growing economic and diplomatic clout, and so abandoned the strategy of engagement and sought instead to curb China’s further rise. This, they concluded, required demonizing China as a global rule-breaker and cajoling other nations to join the US in isolating Beijing.

This new strategy was first articulated in a July 2020 speech by then–Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at the Nixon Presidential Library in California. The People’s Republic of China (PRC), he asserted, is not a “normal, law-abiding nation” but rather an ideologically driven autocracy bent on world domination. It bullies weaker powers in its immediate neighborhood, especially those with claims to oil and fishing rights in the South China Sea, and treats international agreements “as conduits for global dominance.” If we don’t work collectively to reverse Beijing’s expansionist drive, Pompeo declared, it will “subvert the rules-based order that our societies have worked so hard to build.” To prevent this, he argued, will require not only a powerful US military riposte but also the combined efforts of “a new grouping of like-minded nations, a new alliance of democracies.”

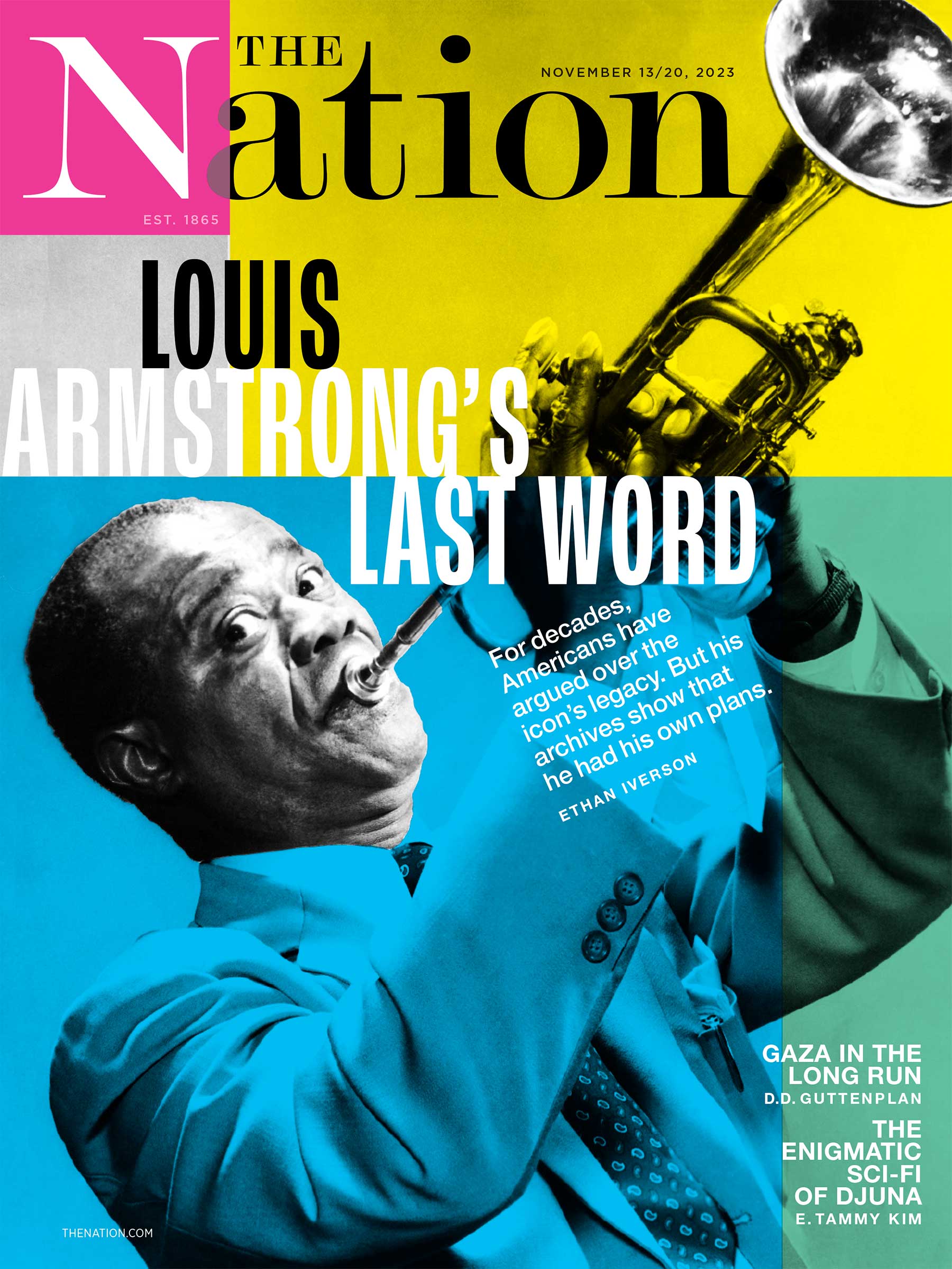

Current Issue

Although criticized by many analysts at the time for its excessively provocative tone, Pompeo’s speech has served as the blueprint for the Biden administration’s policy toward China. “The PRC is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it,” states the administration’s National Security Strategy of October 2022. The only way to prevent such a catastrophe, it argues, is by building a coalition of like-minded states that are committed to defending the existing world order against Chinese predation, as originally suggested by Pompeo. “A free and open Indo-Pacific can only be achieved if we build collective capacity for a new age,” the strategy document affirms. “We will pursue this through a latticework of strong and mutually reinforcing coalitions.”

As indicated by the National Security Strategy and other key administration statements, China is viewed in Washington as the principal threat to US global primacy and, as a consequence, halting China’s advance has been designated the overarching goal of US foreign and military policy. As affirmed in the National Defense Strategy of October 2022, “The People’s Republic of China is the overall pacing challenge for US defense planning.” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has commanded vast attention in Washington and prompted a massive US response, but has not altered this fundamental outlook. Rather, it has obliged the White House to portray its muscular response to the invasion as a defense of the larger, Chinese-oriented rules-based order.

This conflation of the Ukraine conflict and US efforts to isolate China was evident, for example, in Biden’s September 2022 address to the UN General Assembly. “We will stand in solidarity with Ukraine,” Biden declared, providing whatever munitions and other aid the Ukrainians needed to resist Russian aggression. But this is just part of a larger struggle, he avowed. “The United States is determined to defend and strengthen democracy at home and around the world [and] to defend the sovereign rights of smaller nations as equal to those of larger ones; to embrace basic principles like freedom of navigation [and] respect for international law”—an obvious reference to China, given its history of harassing the fishing and oil-drilling vessels of its neighbors in the South China Sea.

Biden’s vigorous efforts to assist Ukraine in its bloody struggle to drive off Russian invaders has drawn praise from many in Europe and the US who are appalled at Russia’s brutal tactics and fearful of further Russian aggression in the region. But his attempts to portray these efforts as part of a global drive to defend what is perceived as the US-dominated “rules-based order” has not received such widespread acclamation. In fact, many leaders of the developing complain that the vast flow of Western aid being sent to Ukraine has siphoned off funds once earmarked for development in the Global South—including for overcoming the severe impacts of climate change—and that sanctions imposed on Russian energy have boosted fuel and food costs in their own countries, causing widespread hardship.

For many in the developing world, moreover, US efforts to form a global coalition of democracies to combat Russia and China has been viewed as self-serving and hypocritical, given Washington’s support for authoritarian governments when convenient and its recurring interventions in the Middle East. “The crux of the matter is that African countries feel infantilized and neglected by Western countries, which are also accused of not living up to their soaring moral rhetoric on sovereignty and territorial sanctity,” observed Ebenezer Obadare, senior fellow for Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

And that was before Hamas conducted its murderous rampage in Israel and the Israeli government responded by cutting off deliveries of food, fuel, water, and electricity to the Gaza strip and commenced an intense air and ground attack on that narrow, densely populated area, causing thousands of civilian casualties. Understandably, President Biden rushed to Israel’s defense, citing America’s long-term ties to that country and widespread public dismay over the horrors inflicted by Hamas on October 7. But, once again, Biden also attempted to conflate US support for Israel with his larger project of defending the rules-based international order against its supposed enemies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

“We’re facing an inflection point in history,” he said in his October 19 speech on Israel and Ukraine. “If we walk away and let Putin erase Ukraine’s independence, would-be aggressors around the world would be emboldened to try the same. The risk of conflict and chaos could spread in other parts of the world, including in the Indo-Pacific (i.e., the South China Sea and Taiwan), in the Middle East.” Only by flooding Israel and Ukraine with weapons, he avowed, can we deter such aggression and protect American values and interests everywhere.

Even in the United States, some key figures—including the new speaker of the House, Mike Johnson—have rejected grand contrivance. In the developing world, however, opposition to it is nearly universal. Contending that Israel’s blockade of Gaza and its unrelenting air and artillery strikes on civilian infrastructure constitute war crimes akin to those conducted by Russia against Ukraine, many prominent officials have accused Washington of blatant hypocrisy, saying it applies its “rules-based order” only to its adversaries, while turning a blind eye to blatant violations by its allies.

“Anywhere else, attacking civilian infrastructure and deliberately starving an entire population of food, water, basic necessities would be condemned, accountability would be enforced,” said King Abdullah of Jordan, an erstwhile US ally. International law loses all value if it is implemented selectively.”

With Israel continuing to bomb and shell mosques, hospitals, and apartment buildings in Gaza and the Biden administration failing to exert pressure on the Israelis to halt the carnage, it is hard to imagine how the White House can resurrect international support for its so-called rules-based order. It could, of course, reconstitute its overseas “order” as a US-led alliance of the NATO powers plus Australia, Japan, and South Korea—an entirely plausible, if dreadful outcome—but this would by definition exclude most of the rest of the world. With no meaningful future for Biden’s preferred system, that rebuffed majority will waste no time constructing alternative systems of global governance. That process, in fact, is already under way.

Considering the Alternatives

The most thoroughly developed and articulated alternative to the US-led international order is the one advanced by its arch rival, China.

Despite its modern economy and wealthy coastal enclaves, China continues to identify itself as a “developing” nation and a leader in the struggle to free the Global South from the vestiges of colonialism. In place of the US-dominated world order, it claims to be constructing a more egalitarian one in which the tyranny of Western banks and financial institutions will be overcome through the establishment of new, multinational arrangements unchained to the dollar and governed in a more inclusive manner. Needless to say, these new arrangements would largely be anchored in China and their operations conducted by Chinese banks and state-owned enterprises.

For the past 10 years, China’s principal vehicle for realizing this vision has been its “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a massive infusion of infrastructure spending aimed at spurring development in the Global South and linking those countries’ economies to its own. During that time, Beijing has disbursed nearly $1 trillion—largely in the form of loans—to finance the construction of ports, roads, airports, railroads, and other infrastructure in recipient states. However, Beijing’s insistence on credit financing and its reliance on Chinese state-owned firms for much of the construction work has generated considerable discontent in some of these countries, as projects have faltered and recipient states have become saddled with heavy debt loads. Nevertheless, China’s willingness to finance major infrastructure projects in Africa and other areas long ignored or spurned by the West—whether for concern over human rights or pervasive corruption—has earned it considerable good will and political influence.

Recognizing the growing criticism aimed at the BRI because of its onerous credit terms and excessive focus on building large, often wasteful “prestige” projects (such as giant stadiums and airports), China’s leaders have sought to revise its blueprint, placing greater emphasis on smaller, community-oriented initiatives. At the same time, they have attempted to downplay Beijing’s centrality in the oversight of these endeavors while highlighting the leadership role of partner nations. “Belt and Road cooperation was proposed by China, but its benefits and opportunities are for the world to share,” President Xi Jinping told representatives of over 130 states, many from Africa, at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing on October 18.

There can be no doubt that many developing nations, especially those represented at the Belt and Road Forum on October 18, will continue to view China as a source of investment funds and diplomatic support. It is unlikely, however, that a significant number of them will embrace a China-centric world order as an alternative to the US-dominated one. Rather than welcome a new global order dominated by Beijing, most would prefer a more fluid system, dominated neither by Beijing nor Washington but allowing them to trade and cooperate with both—and, for the more advanced among them, to eventually move into the ranks of the world’s top power brokers.

Of those advocating a more diverse, “multipolar” order, none has been more prominent than Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India. Although often criticized at home for his repressive policies and embrace of Hindu nationalist extremists, Modi is admired by many in the developing world for his public defiance of both Beijing and Washington and for his advocacy of a more pluralistic, egalitarian world order. “This is the time for all of us to move together,” he declared at the opening session of the G20 summit in New Delhi on September 9. “Be it the divide between North and South, the distance between East and West, management of food and fuel, terrorism, cyber security, health, energy or water security, we will have to find a solid solution to this for future generations.”

Among other initiatives, Modi is a prominent supporter of the BRICS initiative, perhaps the most tangible expression of an alternative world system. Although not a formal entity like NATO or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, with a permanent headquarters or secretariat of its own, the BRICS provides an important forum in which leaders of the ensemble can meet and discuss alterations to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and other Western-dominated institutions, allowing for a greater governance role by nations of the Global South.

At their most recent summit, held in Johannesburg, South Africa, on August 23–24, leaders of the BRICS reaffirmed their commitment “to enhancing and improving global governance by promoting a more agile, effective, efficient, representative, democratic, and accountable international and multilateral system.” Also, in response to widespread interest in the group among nations of the Global South, they agreed to add six new members—Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—to their ranks. The 11 members of the enlarged group, now to be called BRICS+, will encompass 45 percent of the world’s population, possess some 44 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves, and produce about one-third of its food. Despite the differences among its members, this is a bloc that cannot be ignored.

Washington’s Critical Choice

As noted earlier, President Biden opened his October 19 speech on Israel and Ukraine by declaring, “We’re facing an inflection point in history.” From his perspective, this means that Congress and the American people—along with key allies—must support his last-gasp effort to preserve (his version of) the rules-based order against its multiplying enemies. But a correct understanding of this moment would be that Biden’s US-centric order is now broken and that alternative governing models are proliferating. Unless the United States engages in this process and adopts a less domineering role, it will soon find itself sidelined in a world where other voices carry more weight.

Exactly what positions the US should stake out in this critical process will require vigorous and extended discussion by policymakers, academics, and an informed citizenry—including, importantly, readers of The Nation. But one thing is clear: The United States must stop devoting all its foreign policy resources to containing China and instead should partner with Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and other leaders of the Global South in developing a more egalitarian and pluralistic world order—one in which those countries play a greater role in global governance and the needs and aspirations of their peoples are accorded greater priority in setting the global agenda.

-

Submit a correction

-

Reprints & permissions