Somewhere in the hills above Malibu, drenched in California sunshine and sitting side by side in a used white Volkswagen bug, two teenage boys realized they were lost. They’d been looping their way along an open road, past shady groves and canyons, and in doing so they’d gotten turned around. This was the early 1960s, and the boy driving the car was Albert Einstein—yes, this really was his given name, years before he changed it to Albert Brooks. Riding shotgun was his best friend and classmate from Beverly Hills High School, Rob Reiner.

Brooks had inherited the car from one of his older brothers, and he’d made it his own by removing the handle of the stick shift and replacing it with a smooth brass doorknob. After several failed attempts to find the Pacific Coast Highway, which would take them home, Brooks and Reiner came upon a long fence surrounding a field where a single cow was grazing. Albert “stopped the car and he leaned out the window and he said, ‘Excuse me, sir! Sir?’ and the cow just looked up,” Reiner told me. “And he said, ‘How do you get back to the PCH?’ And the cow just did a little flick of his head, like he was flicking a fly away, and went back to eating.” Without missing a beat, Albert called out, “Thank you!” and confidently zoomed away. “I said, ‘Albert, you just took directions from a cow!’ And he said, ‘Yeah, but he lives around here. He knows the area.’ ”

Reiner is telling me this story, dissolving into laughter as he does, to make two points. The first point is that Albert Brooks has impeccable comic timing, a quality that, among other talents, has made him a hero to multiple generations of comedians, actors, and directors who are themselves legends. The second point is that Brooks has always been this way.

Reiner remembers exactly his first impression of Brooks (Wow, this guy is arrogant ) and also his immediate second impression (This arrogant guy is mortified ). They both did high-school theater, and got to talking after their first class together. Brooks began to casually brag about the famous people he had met—they were Beverly Hills kids, after all. “He comes up to me, and in his cocky kind of way he says, ‘I know Carl Reiner,’ ” Rob Reiner told me. “And I said, ‘Yeah, I know him too. He’s my father.’ Oh my God, he was so embarrassed.” They instantly became friends, and have been close ever since—even living together for a stretch. One acquaintance described them to me as more like twins than brothers.

But although Brooks and Reiner pursued careers in the same industry, and both found great success, they didn’t choose the same path—personally or professionally. Brooks’s decisions over the years occasionally confounded his oldest friend, and worried him. Looking back now, however, something has become startlingly clear. If it is the case that by high school a person is already on some fundamental level the person they are destined to become—and Reiner believes this to be “totally true” of Brooks—then Brooks was fated to be not just the godfather of American comedy but also a man who would prove that humor in the face of catastrophe can sometimes save your life.

One thing you notice if you spend any amount of time with Brooks is that his manner of speaking—in musical swells that rise and fall—is not just something that his characters do, but something that he does. Think of Brooks in Broadcast News, the pitch of his voice going higher for emphasis as his character tries to persuade the woman he’s crazy about not to go out with another man: “I’ve never seen you like this with ANYbody. And so DON’T get me wrong when I tell you that TOM, while being a very NICE guy, is”—here he shifts into a whisper-shout—“THE DEVIL.” Off camera, this way of speaking, depending on the topic at hand, comes off as relieved, annoyed, insistent, or pleading. When you agree with him, he will often respond, “This is what I’m SAYing.” And when he disagrees with you, it’s “no NO,” always no twice, always with the emphasis on the second no.

The director and Simpsons co-creator James L. Brooks (no relation) spent part of this past winter directing Albert in the forthcoming Ella McCay, a political comedy set in the recent past. James told me that he knew he had to cast Albert based on just two words in the script: Sit, sit. “Which to me is very Albert,” James said. “It’s just the most Albert line.” The scene involves a classically Brooksian mode of imploring condescension—a quality deployed perfectly, for example, in the opening scene of Modern Romance, when Brooks’s character is dumping his girlfriend: “You’ve heard of a no-win situation, haven’t you? … Vietnam? This? ”

Brooks is tall, and often dresses monochromatically. A go-to outfit is black pants and a dark button-up shirt over a black tee, with a black fedora. He talks with his hands, and when he’s not gesturing with them, he fidgets. This comes off less as nervousness than as a kind of perpetual motion. When Brooks wants something, he is relentless. And he is impatient. He has a reputation for being extremely difficult to say no to. “Because he’s persuasive,” Reiner told me. “And he’s right 90 percent of the time.”

But Brooks himself has no trouble saying no. He has repeatedly turned down the various Hollywood luminaries who asked him to star in their films—parts that ultimately went to Tom Hanks, Billy Crystal, Robin Williams, and Steve Martin, and in several cases altered the trajectory of their careers. He was offered the role Hanks played in Big (1988), the role Crystal played in When Harry Met Sally (1989), and the role Williams played in Dead Poets Society (1989), to name only a few. (Brooks was somewhat reluctant to discuss this with me, as he didn’t want to sound “stuck up, because there are so many of them.”)

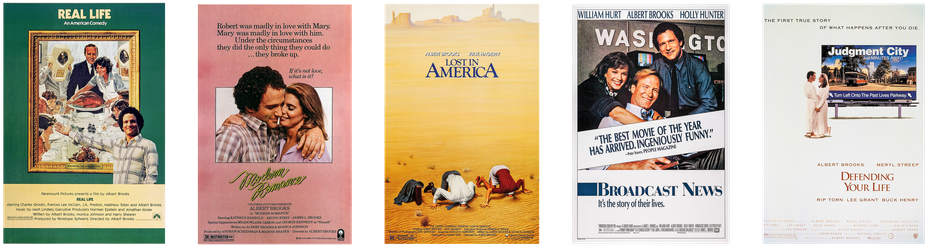

Instead, he went his own way, and has single-handedly shaped modern American entertainment to an astonishing degree. Pick a random moment in film or television from the past half century, and Brooks is often nearby. He was a repeat guest on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show in the golden era of late-night television. Lorne Michaels asked him to be the permanent host of Saturday Night Live before it launched. (In declining the offer, Brooks suggested the rotating-guest-host format that has defined the program ever since.) Brooks wrote a satirical short called The Three of Us for SNL that seemed to predict the premise of Three’s Company, two years before Three’s Company existed. His first role in a big film was in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). His mockumentary (Real Life, 1979) came out five years before Reiner’s This Is Spinal Tap. And for The Associates, the sitcom that gave Martin Short one of his first breaks, Brooks composed the theme music.

Then there is the string of critical hits that he wrote, directed, and starred in, including Modern Romance (1981), about a man who breaks up with his beautiful girlfriend, then spends the rest of the film trying to get her back; Lost in America (1985), about a yuppie couple who quit their jobs to travel across the country in a Winnebago; and Defending Your Life (1991), a comedy about what happens when you die, which also starred Meryl Streep. Plus his role in Broadcast News (1987), which earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. He was considered a lock for another Oscar nomination after he played a vicious L.A. gangster alongside Ryan Gosling in the gorgeously shot film noir Drive (2011), but it didn’t happen. (“I got ROBBED,” Brooks tweeted the morning the nominations were announced. “I don’t mean the Oscars, I mean literally. My pants and shoes have been stolen.” What he’s actually pissed off about, he told me, is that he can’t get more roles as villains. He loves playing the bad guy.) He was the voice of the father clown fish in Finding Nemo (2003) and did the voices for Hank Scorpio and Jacques (among many others) in The Simpsons. Petey, the decapitated parakeet from Dumb and Dumber (1994), was inspired by Petey the cockatiel in Modern Romance.

Although he’d wanted to be an actor since he was a child, Brooks didn’t want to be just an actor. He was and is a writer first, and tends to prefer seeing his stories to completion by acting in and directing them. Brooks is beloved, in part, for the big-eyed, wrinkled-brow, heart-on-his-sleeve quality he brings to many of his characters—part puppy dog, part … what, exactly? “You know, you’re talking about the secret sauce, so it’s hard,” James L. Brooks told me. “There’s an intrinsic vulnerability to him.” In real life, however, Brooks is far more confident—if still highly methodical. “He’s cautious about everything,” Reiner told me. “He can get obsessed about every little thing.”

Civilization-destroying earthquakes, for one, are never far from Brooks’s mind. (“Only because it’s going to happen, and I don’t know if it’ll happen in my lifetime,” he told me.) He is something of a hypochondriac. (“If I lived with a physician, they would have left me.”) He worries about an uprising of the nation’s youth against the Baby Boomers. (The plot of his 2011 novel, 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America, hinges on all three of these fears: A 9.1-magnitude earthquake nearly destroys Los Angeles; the superrich are the only ones who can afford decent health care; young people plot a violent revolt against “the olds.”) There are more mundane worries: He is fastidious about avoiding saying or doing things that could make him seem cocky, or stupid, or bougie. He also fears nuclear war. (“You know, I’m old-fashioned.”)

On film, death comes quickly, and hilariously, for Brooks. In Defending Your Life, which he wrote and directed, his character buys himself a new BMW on his birthday and is hit head-on by a bus almost immediately upon taking it out for a spin. He is, at the time, singing along to the West Side Story soundtrack, belting out Barbra Streisand’s rendition of “Something’s Coming.” In Private Benjamin (1980), the story begins with Brooks’s character marrying a woman played by Goldie Hawn, then dying while in the act of consummation on their wedding night, less than 11 minutes into the film (the consummation itself takes seconds). In a 2021 cameo on Curb Your Enthusiasm, Brooks throws his own funeral, so that he can watch a livestream of his friends eulogizing him while he is still alive.

While reporting this story, I talked with Brooks numerous times over many months. We met in person in L.A., we talked on the phone, we texted. For the conversations we’d planned ahead of time, he was never once late, not even by a minute. He’s the kind of person who will text you back instantly, no matter the hour or time zone. This is a quality I gather he expects from others in return. “Albert loves hyper-preparedness,” the actor Sharon Stone told me.

Stone co-starred with Brooks in The Muse, the 1999 film—which Brooks also wrote and directed—about a director who finds out that Hollywood’s best ideas all come from one woman. (Brooks’s co-writer was Monica Johnson, a close friend and collaborator who died in 2010.) Stone described Brooks to me as an “intellectual giant” who has no time for people who don’t work hard, but who never lost his temper on set. She also described him as peerless, basically. I had asked her where she would situate him among other movie stars roughly of his generation—say, Bill Murray or Steve Martin—and she told me none of them even comes close. (Murray doesn’t have the focus and Martin can’t keep his head out of the clouds, she said. Plus, neither can direct.) The only person she could think of who approached Brooks’s brilliance, she said, was Garry Shandling, who died in 2016. “There are people who have great talent,” Stone told me, “but there aren’t many people who can take that talent and have the discipline and the huge ability to be the general, and put a huge project together and then push it all the way through.”

Stone loved working with Brooks, and she particularly appreciated his bias toward action. If somebody wasn’t prepared, he would decisively and calmly move on without them—not exactly Zen about it, but sanguine. “He doesn’t have any patience if you’re not ready, if you don’t know your lines, if you don’t have your shit together,” Stone said. Later, she put it to me this way: “Albert’s a winner. And if you were running a relay race with Albert and you handed him the torch and the person next to him fell on the ground, Albert could jump over that person and run to the finish line … Someone would say, ‘You know, you jumped over that person,’ and he would say, ‘People who lay on the ground don’t win races.’ ”

I asked her if others found this quality off-putting. “People who lay on the ground would think Albert is mean,” she said. Also, she said, “he’s super bored by people who aren’t smart.” Despite his improvisational skills (see: his many voice appearances on The Simpsons, where he is a legend in the writers’ room for his riffing), Brooks is not one for winging it. Or, as he once put it to me: “Come anally prepared and let’s do the silliness on purpose when we want to.”

Another time, when I asked Brooks if it irritated him to be around people who aren’t as quick or clever as he is, he demurred, unconvincingly. A low tolerance for people who cannot keep up would be understandable. His mind gallops through conversations—there is never a missed opportunity for a joke, yet his joke-telling doesn’t come off as striving, only calibrated to the moment. One friend of his likened this quality to watching a professional athlete in a flow state. Consider this exchange, from when Brooks appeared on Larry King’s radio show in 1990, which left King gasping with laughter:

King: Do you ever order from 800 numbers late at night from on television? I get the feeling you do.

Brooks: Do you?

King: I don’t, but I think you do.

Brooks: I bought a wok and a vibrator. Actually, it was the same thing. A vibrating wok.

The people who know Brooks best still marvel at how naturally humor comes to him. James L. Brooks told me the story of a party he attended sometime in the late 1970s, where he’d noticed a small crowd gathering around a table to watch some guy doing card tricks. The guy was oozing charisma, and had charmed the people around him out of their wits. But it took him a minute to realize what was actually happening. “This guy doing card tricks had no idea how to do card tricks. He was just talking about 45 miles an hour. It was Albert Brooks. And he was just being hilarious.”

Rob Reiner told me about another party, where Brooks was so funny that people almost felt they were witnessing the birth of a new art form. “People were screaming laughing,” Reiner said. “And when he finished, it was like he’d been on a stage. He left the party, and a half hour later, the hostess of the party comes up to me and says, ‘Albert’s on the phone. He wants to talk to you.’ And so I get on the phone and I said, ‘Albert, what’s up?’ And he said, ‘Listen, Rob, you gotta do me a big favor.’ I said, ‘What is it?’ He said, ‘I left my keys in the house there and I can’t come back to get them.’ Because he’d finished his performance. He didn’t want to come back. So he had been wandering around for, like, 20 minutes trying to figure out what to do … That’s the way his mind works.” Reiner grabbed Brooks’s keys and went outside to find his friend.

Last year, Reiner released a documentary about Brooks’s career called Defending My Life, a project Reiner had wanted to pursue for years, inspired by My Dinner With Andre, Louis Malle’s famous 1981 film featuring the theater director André Gregory and the actor and playwright Wallace Shawn having a sprawling conversation at Café des Artistes, in Manhattan. For years, Brooks said no to the idea before finally relenting. “I’ve always felt he is the most brilliant comedian I’ve ever met,” Reiner said. The two have sometimes drifted apart, but they always drifted back together, Reiner told me. One argument in particular stands out in Reiner’s memory.

“I remember this distinctly,” Reiner said. “He would always ask me, ‘How does my hair look?’ And, you know, when he was young he had that Jew fro. And it looked the same every time. Every time he asked me, ‘How’s my hair look?’ And I would say, ‘Albert, it looks fine.’ And then one time we’re in the car and he kept asking me, ‘How does my hair look?’ And I said, ‘Albert, it looks the same! It looks the same every single time I look at it! It’s always the same!’ And he got so mad at me, he threw me out of the car. He said, ‘Get out of this car!’ He got mad at me because I wouldn’t tell him how his hair looked.”

Brooks remembers a different argument they had, decades ago, about the enduring star power of classic film actors—“the Cary Grants, the Clark Gables.” Reiner had remarked on how stars like that were immortal, the kind of leading men who “will never go away,” Brooks recalled. “And I said, ‘Everyone’s going away.’ And, you know, my kids don’t know who Cary Grant is unless I force them and say, ‘That’s Cary Grant.’ Every generation has their own people. And it’s remarkable how fast everything else goes away.”

The term comic’s comic is overused. But with Brooks, it fits. Judd Apatow, Conan O’Brien, Sarah Silverman, Chris Rock, and too many others to name have all cited him as a formative influence. James L. Brooks told me the story of standing in the living room at some gathering with Steve Martin when Martin spotted Brooks and got starstruck—“nervous, like a kid at Christmas,” he said.

While the critics who love Brooks often lament that his films have not enjoyed more commercial success—“Albert almost intentionally makes noncommercial movies,” Sharon Stone told me—what they miss is that he has, over the course of his career, repeatedly chosen fealty to his own artistic vision over anyone else’s desires, for him or for themselves. And he has done so with the clarity of a man racing against time, someone who knows that we only get one go-round, and tomorrow is never promised.

Big, When Harry Met Sally, Dead Poets Society—all became generational cinematic hits, as close to timeless as they come. But to Brooks, the decision to turn down these roles was obvious. With Big, he just couldn’t see himself playing a little boy. And anyway, he’d been actively trying to avoid New York City since at least the 1970s, back when Lorne Michaels had come calling. “What I really was not going to do was go to New York and stay up until 11:30 to be funny, and risk getting addicted to coke,” he told me. Later, as he read the script for When Harry Met Sally, which Reiner was directing, he knew right away that he shouldn’t do it. “I was being called ‘the West Coast Woody Allen,’ ” Brooks told me. “And I read this lovely script that felt like a Woody Allen movie—the music and everything. And I thought, If I do this, I’m Woody Allen forever.”

The Woody Allen comparisons make only a superficial kind of sense. It’s true that both Allen and Brooks write, direct, and star in their own films. Both are self-deprecating leading men. Both write unforgettably funny dialogue on a line-to-line level. (They’re also both frequently described as neurotic—an adjective that, as Brooks once acidly complained to me, is simply the lazy film critic’s code for “Jew.”)

But where Allen’s films are oriented inward—self-deprecating, yes, but also self-obsessed bordering on narcissistic—Brooks’s films radiate outward, almost galactically, an expanding universe all unto themselves. Again and again, he poses the most profound questions possible—What does it mean to live a good life? Where do we go when we die? What if we weren’t afraid?—then filters them through his sense of humor, and explodes them into a meditation on the human condition.

So New York was out of the question. And anyway, why bother starring in a film you didn’t write? Why let somebody else direct something you did write? And why direct something you can’t star in? More than that, Why wait ? Wasn’t that the lesson he learned the hard way when he was only 11 and a half?

Everett Collection; Geffen Pictures / Everett Collection; 20th Century Fox Film Corp. /

Everett Collection; Warner Brothers / Everett Collection)

Not many people can pinpoint the exact moment when they became who they are, the formative experience from which the rest of their life unspools. But Brooks can: November 23, 1958. The Sunday before Thanksgiving. His mother, Thelma; father, Harry; and one older brother, Cliff, left home for the Beverly Hilton to attend a roast put on by the local Friars Club, which his father helped run. The event was in honor of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Hollywood royalty whom Harry Einstein introduced—in a perfect deadpan that made the audience roar—as his very close personal friends “Danny” and “Miss Louise Balls.” (In a recording of the roast, you can distinctly hear Arnaz’s honking laugh rise above the hysterics of the crowd.)

Einstein was a superstar comedian himself, known for his dialect humor and for his popular radio alter ego Parkyakarkus (say it aloud to get the joke). Over the next 10 minutes, he had the audience members in tears. When Einstein finished, he made his way back to the dais, where he was seated next to Milton Berle. With the audience still clapping for him, the color suddenly drained from Einstein’s face, and he slumped over onto Berle. Frantic attempts to resuscitate him began right away, and in the panic, the singer Tony Martin took the microphone in an attempt to distract people with one of his hit songs. Meanwhile, a doctor in the audience made an incision in Einstein’s chest with somebody’s pocketknife, and another doctor fashioned a makeshift defibrillator by peeling the insulation off a nearby lamp cord. None of it worked. Einstein, at 54 years old, was dying of a heart attack while Martin sang a song that took on dark—and to Brooks, in retrospect, darkly funny—meaning: “There’s No Tomorrow.” Arnaz eventually grabbed the microphone: “They say the show must go on,” he said. “But why must it?” With that, the evening was over.

Although Einstein’s death was shocking—it made national headlines—it was not unexpected. He had suffered from a serious spinal issue and a related heart condition, and was by then using a wheelchair. When he did walk, Brooks remembers, he lumbered “like Frankenstein.” He looked terrible. And life in the Einstein household was largely oriented around accommodating his ill health. Brooks’s earliest memories of his father, though, are happier ones. They would take long drives out to Santa Paula, past orchards where the tree branches were heavy with oranges and lemons. Back at home, they would goof off. “Sometimes at the dinner table, he would be more like a kid and play with a fork,” Brooks recalled. “And my mother would get angry like she would with a kid. And we would all laugh.”

The Einstein household seems to have been genetically predisposed for humor. One of Brooks’s brothers, Bob Einstein, grew up to have a successful comedy career. You may remember him as his stuntman character, Super Dave Osborne, or as Marty Funkhouser on Curb Your Enthusiasm. (He died in 2019.) Their mother, Thelma Leeds, was also in show business—she and Harry met in 1937 on the set of a film they were starring in. After Brooks’s film Mother came out in 1996, Entertainment Weekly asked her to write a review, including a grade of the film. Brooks was convinced that she’d give it a middling review just to be funny. “I said, ‘Listen to me’—and this is not a joke—‘you have to give it an A,’ ” Brooks recalled. (She ended up giving it an A+++.) Despite his parents’ comedic gifts, he insists that they didn’t name him Albert Einstein as a joke. “I swear to God, it was like, ‘You know, he’s a wonderful man. Let’s give him that name.’ ”

For Brooks, the death of his father was not just a tragedy but the inevitable realization of a long-held premonition. He had been bracing for it for as long as he could remember. “From the moment I could conceive anything, this is what I was expecting. So, you know, then you start trying to fool God,” he told me. “You tell yourself, Well, I’m just not going to get close. And You’re not going to take anyone from me. I’m just not going to love him. You know, you do whatever you have to do, to make it okay. It forced early thoughts of the end before the beginning.”

“I never felt he didn’t love me,” Brooks told me later. “I just felt it was going to be quick. That, I think, colors a part of your life.”

The actor and director Jon Favreau, who is close friends with Brooks, can relate to what he went through. Favreau’s mother died of cancer when he was a child. “The idea that catastrophe could be just around the corner is something that is baked into your psyche when you experience something that grave that early,” Favreau told me. That attitude, expressed artistically, can take many forms. “It can go different places with different people, but with Albert it definitely went to This has to be funny. I want to bring the house down. And that’s where I think somebody like Albert finds that he has a superpower. Through his intellect and through his humor and through whatever experiences made him who he is, what comes out of that machinery is laughter and amusement and human insight that allows you to deal with subjects—mortality—that are presented within the framework of something that is hilarious.” That, Favreau told me, is Brooks’s “magic trick.”

After his father died, Brooks settled into a new kind of normal. He and his friends would spend hours recording mock interviews on giant tape recorders, pretending to be radio stars like his dad was. “I was really sort of doing these shows for no one for a long time,” he told me. He played football and sometimes hitchhiked to school. He watched television—as many hours a day as he could get away with. He was also music-obsessed, and amassed a prized collection of records, building his own stereo with quadraphonic surround sound. This was in the early days of stereophonic recording, and Brooks still remembers the first stereo album he bought to show off the new technology: Stan Kenton’s version of West Side Story. “They were really doing the right-left thing,” he said. “You know, DA-dah, BA-dah, DA, dah! Right speaker! Left speaker! Right speaker! Ba-dah-dah-dah-dahhhh, ba-dah-bah-dah-ba-dah-daaaah ba-doo ba-doo. Your head would be moving like a tennis match.”

Brooks is prone to spontaneously breaking out into song, or more accurately, breaking out into sound, without the lyrics, perhaps an artifact of his theater roots. After high-school graduation, in 1965, Brooks and Reiner did summer theater in Los Angeles. After that, Brooks went to L.A. City College before winning a scholarship to attend the drama program at Carnegie Mellon (then called Carnegie Tech), in Pittsburgh. A shoulder injury from his football days kept him out of the Vietnam War, an injury he now sees as his life’s blessing. After a year in Pittsburgh, he dropped out and returned to Los Angeles.

“When he came back from Carnegie Tech, he wasn’t thinking about comedy, and I couldn’t believe it,” Reiner told me. “He wanted to change his name to Albert Lawrence—his middle name is Lawrence. And I said, ‘Albert, what are you doing? You’re the funniest guy I know. You’re going to tell me that now all you want to do is be a serious actor?’ The fact is, he is a great serious actor. But I said, ‘You can’t throw away that gift you have. You make people laugh better than anybody.’ ”

Then, in 1973, something frightening happened that left Brooks forever changed. He had just come out with a comedy album, Comedy Minus One, and was on the road promoting it—something he hated doing—with endless performances in dingy clubs and interviews with local journalists. One of these conversations, with a radio DJ, left Brooks feeling deeply unnerved. “A morning man in Boston said to me, ‘Albert Brooks, let me ask you a question,’ ” Brooks recalled. “ ‘Jonathan Winters went crazy. Do you think that’s going to happen to you?’ ” Winters, the superstar comedian and television actor, had been hospitalized years earlier after scrambling up the rigging of an old three-masted sailing ship docked in San Francisco Bay and refusing to come down, insisting that he was “a man from outer space.” Brooks remembers stumbling through an answer: “I don’t know. I hope not. I don’t—I don’t know.”

Later that night, he had his first performance at a jazz club in the Back Bay, where he was supposed to do two shows a night for a week, with an opening act by the singer-songwriter Leo Sayer, who dressed up for his performances as a 17th-century Pierrot clown, complete with heavy makeup. Sayer’s whole record company showed up, and in a surreal demonstration of devotion, “everybody in the audience was dressed as a clown,” Brooks told me. (This may sound like some sort of chemically induced hallucination, but Brooks assured me it was not. “No drugs. None,” he said.)

He did his first show and went back to his hotel across the street to get ready for the next one. But when he got there, “I had, like, a brain explosion,” Brooks told me. “I mean, something happened. All of a sudden, you know, my life was different. I don’t know how to describe it. I was standing in the bathroom. I was holding a toothbrush. And all I could think about is who invented this and why are there bristles on this end? And why are there bristles at all? And isn’t there a better way to brush your teeth? And how come there are sinks? I was starting to unravel, questioning everything. And that in turn made me really scared that I had gone nuts.”

He begged his manager, and the club owner—who by then had come across the street to see what was wrong—to let him skip the second show. The club owner told him he could cancel every other show that week, but he had to go through with the show that night. People had bought tickets! They were already sitting there, waiting in their seats. So Brooks agreed to get back onstage. “I was so detached from my body,” he told me. “Every single word was an effort and was not connected to anything. I was just standing there saying what sounded like English words.” Years later, on a trip to New York, he ran into someone who told him he’d been at the show that night in Boston, and wondered in passing if something had been off. “Did you have the flu?” the person asked. Yeah, something like that.

What actually happened, Brooks told me, is that after he somehow kept his body upright and made his mouth say words until he could get offstage again, he cracked open. After the death of his father—and, frankly, probably before that—he’d built a mental wall so sturdy that he was emotionally untouchable. This wasn’t all bad. “It was very advantageous for the beginning of my career,” Brooks said. He remembers his earliest live television appearances, when friends would be floored by his coolheadedness, his total absence of nerves. “Ed Sullivan, 50 million people live, waiting to go on,” Brooks recalled. “My heart didn’t race. I never thought of it. And I loved that. But the reason for that is I wasn’t open, and I was forced open in that one moment. It was like all the stuff you hadn’t dealt with is here. And, you know, that stuff ’s not meant to be dealt with all at once.”

Confronting the great tragedy of your life this way is suboptimal, especially if it hits you when you’re standing onstage staring at a bunch of clowns. “But it opened up my mind,” Brooks told me. “It made me question everything. It made me much more worried about everything. But it also made me deal with it. And it took a long time to, you know, deal with it.” Looking back now, he said, that night in Boston is what led to everything else. Without that experience, “I don’t think I could have written anything” that came after—at least not anything of real depth and complexity. “I think I would have been a non-nervous, pretty surface person.” Brooks never saw it coming. And there’s a lesson in that, too. “You get humbled by life in one second,” he said. If you’re lucky, the terrible thing that surprises you is something you can survive. His father didn’t get that chance. But Brooks did, and he knew exactly what he wanted to do with it.

Albert Brooks, for the record, is not interested in contemplating what might have been. He doesn’t believe in do-overs. He’s not into time-travel movies (though he appreciates the elegance of the original Twilight Zone, which he sometimes watches on YouTube), or imagined alternative histories, or dwelling on the past. “ ‘What if ?’ is terrible,” he told me, “because what are you going to DO with it, you know?” He swears he isn’t a grudge holder—I asked him specifically about this because I had a hard time believing otherwise. People as meticulous as Brooks sometimes struggle to let things go. “No,” he insisted, “because there’s nothing I can DO.” Worrying about the past is “the biggest waste of time,” he said. “I mean, over the years, the best thing I’ve done for myself is learn to worry about what I can fix.”

This is partly his pragmatism but also his attitude as a writer—writing, he once said, is just a series of solving one problem after the next. He doesn’t believe in writer’s block, not really. “Writing is like building a house,” he told me. “Once you start, you have to finish. It’s a funny concept that there’d be a block in other professions. If you hired an architect and a year later you said, ‘What happened?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know, I was blocked.’ You’d say, ‘What?!’ ” Also, when you write, you’re fully in control. “It’s one of the last things, except maybe painting, that you can do without permission,” he said.

Thirty years ago, if you’d have asked Brooks what he was most focused on fixing, it may have been his love life. He worried, “Oh, I’ll never meet anybody,” he told me. This may seem strange—movie stars don’t typically have a hard time attracting partners—but many of his friends envisioned Brooks staying single, too. “I thought, This guy will never get married,” Reiner told me. “I find it hard to even imagine Albert married,” Sharon Stone told me, not because of how intense he can be but because he is so particular. “It’s that he can’t have this, and he doesn’t like that, and it has to be like this, and he can’t be around this, and it can’t be like that,” she said.

Brooks is a person who is comfortable alone. In the early days of his career, he would workshop jokes by just performing them to himself, in a mirror. He went through a phase when he bought one of those radios that picks up people’s phone conversations, and put it by his bed so he could listen to other people’s problems as he drifted off to sleep. (“It was the greatest soap opera,” he recalled. And also a great way to train your ear for writing realistic dialogue. “That was heaven,” he said with a laugh.) He’s gone through long stretches of solitude over the years.

Brooks likes to joke that he knew he didn’t want to get married until he met someone he could stand getting divorced from. Reiner put it another way: “I don’t know if it applies to Albert, but my mother and father were celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary, and I asked my mother, ‘What’s the secret?’ ” Reiner told me. “And she said, ‘Finding someone who can stand you.’ ”

The painter Kimberly Shlain, it turned out, could stand Brooks. She already knew and loved his films when they began dating. They were married in March 1997 at a synagogue in San Francisco. Their reception was filled with calla lilies and white tulips, and their guests ate lemon cake. For their first dance, a live band played “Someone to Watch Over Me.” (He was 49; she was 31.) The couple have two children, Jacob and Claire, both now in their 20s.

In Defending Your Life, Brooks finds the perfect woman—played flawlessly by Meryl Streep—only once he’s already dead. “We’re opening the door, God forbid, to Albert’s brain,” she said in a 1991 interview about the film. Defending Your Life tells the story of a man who dies young and finds himself among the other recently deceased in Judgment City, a version of purgatory that resembles a New Jersey office park, where you can eat whatever you want without gaining weight and see who you were in various past lives as you await a decision from a supernatural judiciary about whether you lived a good-enough life to move forward in the universe. (If not, you’re sent back to Earth to do better next time.) For Brooks’s character, the key question of his life’s trial is whether he wasted his time letting his fears dominate him. Streep said in the same 1991 interview that when Brooks had come over to persuade her to take the part—they’d first met through Carrie Fisher, a mutual friend—he paced for two hours while explaining the concept of the film to her, but wouldn’t let her read the script.

Stone told me about how after The Muse wrapped and Brooks sent her a copy to watch, she sent him some notes, as she generally did with other directors. “Albert wasn’t interested in my notes,” she said. “In fact, I don’t think he liked that I sent him my notes. I think he was a little bit offended by my notes. And I think it’s because he makes all of his decisions about his films in a quite solitary way. He’s the only director that ever sent me a film to preview that didn’t want notes … He didn’t understand. Like, what did I think I was doing, right? Why would I need notes from you, cupcake? ”

Another time, he’d gotten advice from Stanley Kubrick about how to navigate the business side of Hollywood, and the frustration that comes from having to work with people who care more about money than art. Kubrick had reached out to Brooks to say how much he loved Modern Romance, and asked to see the draft of the script Brooks was writing at the time. So Brooks sent it along, and Kubrick sent it back with notes. “He said, ‘Here, I read the script,’ ” Brooks told me. “You know what? I think he had the WORST comment in the world. And I said, ‘Gee, I don’t think I could do that.’ ”

As I reported this story, legendary comedians kept dying. First there was Norman Lear, who died within hours of a conversation Brooks and I had about how wonderful it was that Lear, at 101, was still alive. Then Richard Lewis died. (“Terrible,” Brooks texted me.) Occasionally, when Brooks experiences some unusual bodily pain, an unwelcome thought will materialize: “I worry, Is this the end? I mean, something’s going to take me down,” he said. For a while, he was just trying to reach the age his father was when he died. Turning 55 was, as a result, “very weird,” he said. When the first of his older brothers died, it was like the loss of a “genetic touchstone,” he said. He’d sometimes try to reassure himself by imagining that he got all of his genes from his mother, who lived into her 90s. He turns 77 in July. “Then you’re in no-man’s-land, you know. My father didn’t come near this age.”

Brooks doesn’t believe in immortality, whether in life or on film. Plenty of writers and directors fool themselves into believing that what they make will last forever. Most works of art, even extraordinary ones, do not. Creatively, Brooks was never motivated by wanting to make something lasting, but instead by seeing art generally—and film specifically—as the ultimate form of human connection. Plus, there was always something beautiful to him about how making a movie and watching a movie required deliberateness on both sides of the screen. “People got in their cars, which meant there was an effort made,” he said. “The lights went down. People were there because they wanted to be there.”

Sometimes Brooks thinks back to one of the original endings he wrote for Defending Your Life. This was before Streep was cast in the film. Before he had conceived of the actual ending, which, as it turns out, is one of the great climaxes in all of film history, complete with a sweeping cinematic score, that feels both enormous and also perfectly earned. “The one I liked the best that I didn’t use was that the movie ended in a pasture, and in the distance was a cow,” Brooks told me. In this version, Brooks’s character didn’t get redemption. He didn’t fall in love. He didn’t get the girl. He didn’t overcome his fears. He didn’t move on in the universe. Instead, he lived his life, then came back to Earth … as a cow. It would have been absurd to end things that way. And funny. Because, really, who knows? But that’s not how the story went.

This article appears in the June 2024 print edition with the headline “The Godfather of American Comedy.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.