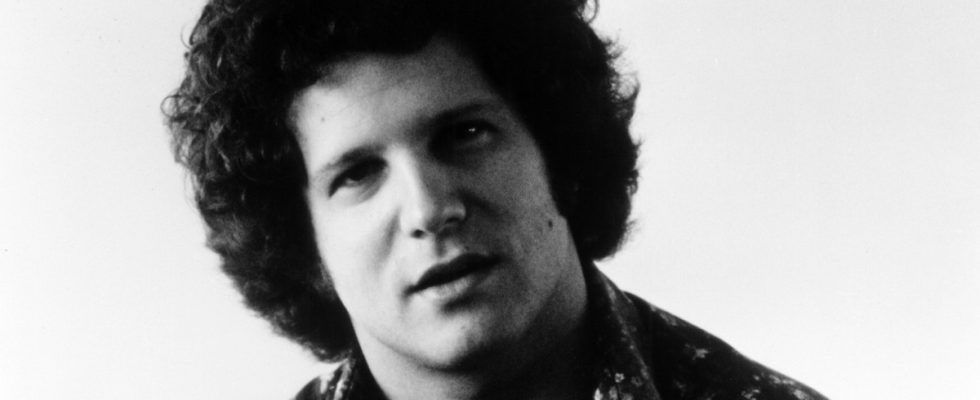

There are two observations in Defending My Life, the new documentary about Albert Brooks by his lifelong friend and fellow filmmaker Rob Reiner, that perfectly capture the imprint that Brooks has made, and continues to make, on American culture.

The first comes from Conan O’Brien: “Albert broke the sound barrier,” the talk-show host says. It was through Brooks’s now-legendary mix of originality, absurdity, exuberance, and sheer brilliance that comedians realized what comedy could be—that “there’s this other place you can go,” as O’Brien puts it. For Brooks, that place entailed beloved bits on late-night television—his celebrity-impressions kit, the mime who describes everything he’s doing as he’s doing it, the elephant trainer who lost his elephant—as well as films like the spoof documentary Real Life and the romantic comedies Modern Romance, Lost in America, Broadcast News, and Defending Your Life.

People have repeatedly compared Brooks to other superstars (Woody Allen, Robin Williams, Andy Kaufman, Steve Martin, and Charlie Chaplin all come to mind), but the truth is that there was no one like him before he arrived, and there has been no one like him since. Few artists have been so consistently ahead of the cultural zeitgeist for so many decades—which leads to the second observation, from Chris Rock: “He’s so good, you can’t steal it. If you stole it, you wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

Defending My Life, which is streaming on Max, will undoubtedly charm the Brooks completists. It showcases the warmth in his friendship with Reiner and the abundant adoration of his comedic peers and progenies, all while taking the viewer on a lively, riotous (and at times moving) tour through Brooks’s life. But even those who only loosely know his work will find value in the film for how it reveals the extent to which his fingerprints are all over American comedy. I caught up with Brooks yesterday about where his ideas come from, the particularities of his writing process, and the art of the ending. Our conversation has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Adrienne LaFrance: Hi, Albert. You got me out of a really boring meeting just now, so thank you for that.

Albert Brooks: Oh! Well, we should just hang up and count a win.

LaFrance: Okay, okay. I once heard that the first time you did The Tonight Show, you did the talking mime and nobody laughed. Did that really happen?

Brooks: I don’t think that was my first time. I didn’t do The Tonight Show ’til I’d done, like, 100 variety shows. The Tonight Show was just another show. I think it might have been the second time.

LaFrance: I ask because the notion of people not laughing at that bit seems foreign to me—and obviously they eventually got it. But something else that’s in this documentary is Rob Reiner talking about how you’re the only comedian who would test out your new material for the first time on national TV. You never tried it out for anybody else first—which is astounding to other comedians.

Brooks: That’s true. I never went to a club until years into this, when I was headlining them. So I didn’t ever have that kind of trajectory. I would be at home. I had an apartment and I had a mirror in the bathroom—I didn’t have a lot of mirrors—so I would use that mirror often and sort of come up with something. And when I liked it, I went down [to one of the TV shows] and did it. And I was fortunate that I lived in an era where that was okay, because the longer it all went on, the more these shows were, Well, what are you going to do? You want to give us a hint? Back then, nobody cared. And I kept doing it my way, but over the years there were more guards at the gate of television.

LaFrance: Throughout your career, you have been very selective and deliberate about what you’ve done. You’ve really trusted your own creative vision and had to fight for it at times. I’m curious how you learned to trust your creative instincts that way.

Brooks: That’s exactly how you do it. I mean, in school, I seemed to be the one that was getting the laughs. I could make my friends laugh. So you start early on—something occurs to you in your brain, and it works. Then that starts to expand, like you don’t know if you can do that on film, and you find out. And then it’s like, Well, gee, if I write this and point the camera here, it seems to be funny to me. It was all about thinking that it was funny. I can’t say I didn’t care what the audience thought, because of course I did. But I didn’t not do something again if it didn’t go well, if I really liked it. And, you know, I don’t know how you can continue and make comedy films if you don’t have that.

There’s a whole other kind of person, and some of them are really good, that do it for the studio. They keep doing it to get the green light, to ring the bell. The studio will say, This didn’t work. Let’s reshoot that. This didn’t work. Let’s reshoot that.

But I only did all of this to get an idea across. And once the idea was across, I felt okay. If you liked the idea, that was great.

LaFrance: Where do your ideas come from?

Brooks: Well, ideas for films were generally bigger thoughts. Real Life, the whole point of that was that here was this emerging way of capturing people’s lives, and I thought, Oh, wait a minute. There’s something more there. I know what this is; I know what that more is.

I always had the simplest part of the idea to start a screenplay. Modern Romance was: “on again, off again, on again, off again, on again, off again.” For Lost in America, it was “life decisions that go badly quickly.” That’s what tickles me. Defending Your Life was a little tougher because I knew it was about a non-heaven story. But I wasn’t sure about the ending.

LaFrance: That’s so funny because I was going to ask you about endings generally, and Defending Your Life specifically. When it came out, some people who knew your work were surprised by the ending. How did you decide how you wanted it to go?

Brooks: I tried a lot of other endings. And most of them involved coming back [to life]. The one I liked the best that I didn’t use was that the movie ended in a pasture, and in the distance was a cow.

LaFrance: And it was you coming back as a cow!

Brooks: Yeah. [Laughs.] But you know, the love story got interesting, and then you have new ideas.

LaFrance: So ideas for films are one thing, but I’m also wondering about ideas for bits—like the one where you claimed to have discovered the long-lost lyrics to Ravel’s Boléro, which is hilarious. Do you remember how you came up with that?

Brooks: Oh yes. That was all off of a concept album called A Star Is Bought. That was a documentary about me making a big hit record. It was sort of patterned after the Motown story. So I was interviewed in it, and lots of people were interviewed—I was going with Linda Ronstadt at the time, and she was interviewed—and the conceit of the album was that I was going to make a cut for every kind of radio station, so this album would become a smash. So this was my classical-music attempt—I claimed to have found the long-lost words to Boléro. [Editor’s note: Pair the main melody with the lyrics “Nowww, we are both standing in the nude! I don’t want to be too rough. Or do anything too crude.”]

LaFrance: Thinking of your bits from that era, and especially the elephant trainer with the frog and the ventriloquist who talks more than the dummy, there’s this absurdist quality to your early work. Do you find that you’re drawn to that quality in the art more broadly?

Brooks: No, no, not necessarily. I am drawn to an individual person who I think is talented and go from there. As a matter of fact, in my opinion, when it’s not done right, it’s annoying.

LaFrance: I guess that’s true for most art.

Brooks: Yeah, but that art especially. I remember Garry Shandling about three months before he died—he was going down to these clubs, and he called me one night and he said, “I think I’ve discovered something, an art form.” I said, “What?” He said, “I get up there and I talk and there’s never a laugh.”

LaFrance: The art of bombing.

Brooks: Yeah. [Laughs.] I said, “Garry, it’s called drama.” It’s the other side of that famous mask!

LaFrance: When’s the last time you did stand-up?

Brooks: A long time ago. I do things occasionally. This was a long time ago, but I did this big event for Mort Sahl—that was 3,000 people. But stand-up as, in the simplest form, I don’t know. It’s been forever.

LaFrance: Do you ever get the itch to show up at the Comedy Store? Do you still have the desire to do it?

Brooks: I do get the desire to do it. Not at the Comedy Store, though. I mean the Comedy Store is a viable question because that’s where people get up—but only once in my life after I was established, and I mean like 20 years in, after not doing it for a while, I went to the Improv. Somebody said, “Come down here! All your friends are here!” And I got up onstage and there was a crowd of people and it was uncomfortable. It was like, Oh God. What am I doing here? But I have been thinking about it lately, because it’s nice when it goes well.

LaFrance: It’s a good feeling.

Brooks: And it also is like the only place where the guards go away. It is the most direct communication.

LaFrance: There’s something pure.

Brooks: And just quick.

LaFrance: I remember reading once that for a while in your 20s, you were hanging out with John Lennon. You called him the funniest Beatle, which always stuck with me.

Brooks: Well, I always thought he was a frustrated comedian. This is what it seemed to me. He obviously could write these amazing songs, but his personality, and the people he liked—this was a guy who wanted to be a comedian. He was cynical and satirical and just responded to anything that was outside of what was expected—this is what he loved. I thought he was a great guy.

LaFrance: Tell me a little bit about your writing process, whether for scripts or jokes or books.

Brooks: Well, the book was different. The scripts were pretty consistent: I would write on tape, and I would play all of the parts and do the screen direction also. And so, dictating like this: Adrienne picks up the phone. No one’s there. It’s a bad connection. Albert’s on the other line wondering if they’re going to talk at all. All of a sudden, the phone rings. Adrienne: “Hey, are you there?” Albert: “Oh, good. At least now I didn’t miss my breakfast for nothing”—that kind of thing. So I could go like that for long runs, then I would have somebody type it up and then it would be in a script form. And then I could take a pencil to it and then I could read it, and I would redo it. The book I did on a computer—because it was way too complicated to dictate a novel. You just can’t, you can’t do it. And I loved that. I loved it.

LaFrance: Judd Apatow has talked about how he really does not like to write with a computer. He prefers dictation because it feels so final to type—like the words on the page look too official or something. You said you loved the experience of writing your novel, 2030, but did it feel more permanent as you were writing?

Brooks: Not at all, because I did the same thing. I wouldn’t go back and read as I went. I would really write almost the whole novel in a first pass. Then the laborious part is going back and doing it again, and then again, and then again. And where you don’t like it, you retype it.

LaFrance: In the documentary, at one point, you refer to “the Albert Brooks character.” Talk about what you meant by that.

Brooks: Well, when I’ve played my own name, I’m not that person—it’s the Albert Brooks character in Real Life. You know, I’m sort of a version of a Hollywood guy. He’s just a guy who has way more, uh, confidence that’s unearned.

LaFrance: Well, and you play an Albert Brooks character on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Larry David said that you were nervous at first on Curb. Were you?

Brooks: Yeah, well, that was his opinion. I don’t know that I was nervous. I think that was at the height of COVID. So everybody was nervous that they were gonna go straight from the set to the hospital.

LaFrance: So that must have been how you came up with the COVID hoarder plotline, where you’re revealed to be stockpiling hand sanitizer and Clorox wipes.

Brooks: That was Larry’s story, so I have to say, he called me with this idea. I thought it was okay. I could do that. And, you know, I hadn’t worked with him. So I was a little wondering exactly how that process worked. I wanted it to be good; if I was going to show up, I wanted to do it right. So I brought as many ideas as I could, and then, inevitably, it’s their choice what to use. But it’s a nice way of working. It saves a lot of time writing.

LaFrance: James L. Brooks, among others, has compared you to both Woody Allen and Charlie Chaplin. I wonder what you make of those comparisons—and also who you would say is the artist or artists you most admire.

Brooks: There’s a very small number of people who make comedy movies that they’re in, that they write, that they direct. It’s not nobody, but it’s a small group. And it takes a certain kind of—I don’t know what it takes—head-butting or determination.

LaFrance: Well, and creativity.

Brooks: Exactly. So in that case, it’s a lovely thing to say because those people are all interesting. I admire a lot of people. I thought Stanley Kubrick was as good as this art form can get. Fascinating. And I was so thrilled that he had some reciprocal feeling. It made me, it made me feel sane. In my life, early on, seeing what movies could be, I don’t think that anybody topped Kubrick.

LaFrance: I have to ask you about Broadcast News. Did you ever wish that it ended differently, that you ended up with Holly Hunter’s character?

Brooks: I didn’t wish it. You know, James tried an ending with them together, and he tried an ending with them alone. And none of it worked for him. So I sort of liked, actually, I thought it was sort of gutsy, what did happen. I sort of liked that.

LaFrance: More realistic, too.

Brooks: It is, and quite frankly, I don’t know that either of those relationships would have worked, because of their careers. It would have been very difficult to stick together.

LaFrance: I will confess I’ve watched Broadcast News infinity times. It’s one of my favorites. What are the films that you rewatch over and over? Or any comfort TV shows?

Brooks: Well, I can’t say that I go to a movie over and over to feel comfortable, but—and this will sound corny because I think most people say this—but I was on an airplane a year ago, and it was a long flight, and what am I doing? I’m watching The Godfather.

LaFrance: You can’t not.

Brooks: The Godfather is the godfather of films you watch over and over and over. I’d have to give that the trophy of the rewatch.