Handing back the clementine tart to my dinner party hostess, I tell her I want a bigger slice. Hardly polite behaviour, especially as I’ve just told her that when we first met, I thought she was a b***h. But after six glasses of wine, I don’t care.

Alcohol has freed me from my responsibilities as a friend, mother, daughter and wife so that I’m guffawing at my own wisecracks, impervious to the feelings of others. In my drunken parallel world, I am attractive, I am witty, I am charming… but my husband Chris looks confused as I make heart shapes across the table at him with my fingers like a teenager.

Six hours later, I am staring into my bloodshot eyes as I rest my forehead against the cool glass of my bathroom mirror. Reminded of the last time I had a hangover of this magnitude, back in December 2021, I am overcome with a familiar sense of shame and nausea.

Antonia Hoyle began her period of sobriety at the start of 2022. But in January this year she became a drinker again…

For more than two years, not so much as a drop of alcohol touched my lips. After nearly three decades of regular, enthusiastic and at times heavy drinking, I credited sobriety with newfound clarity, increased confidence and a stable mood.

The more I learned about the damage alcohol does physically, psychologically and societally, the more determined I was to avoid it. And I’d found it easier than I’d thought.

Having embarked on a new sober life at the start of 2022, I lasted until January 20 this year, when, after 750 alcohol-free days, I became a drinker again. I have drunk six times since then, to varying degrees, of which last weekend’s display was by far the most extreme — a deliberate, if destructive, attempt to see if I still enjoyed the sensation of getting drunk.

I didn’t make the decision to drink again lightly. Most of us are aware of the dangers of alcohol, but I’d reached the disappointing conclusion that it seemed integral to my social life and sense of belonging. Unlike so many other sober people I admire, in a society still obsessed with alcohol, I am too weak to go against the grain.

On top of that, increasingly sobriety had come to feel like another form of perfectionism, a way of proving my worth, a stick to beat myself with — less an achievement than a millstone around my neck. The longer I abstained, the further I had to fall from the pedestal on which I’d put myself. I knew drinking again would trigger complex feelings of guilt and relief, shame and liberation, but I was intrigued to see whether it would prove worth it in the long run.

For much of my adult life, alcohol has been part of my identity, turning me into ‘fun Toni’ at parties and helping me switch off after a stressful day.

Two pregnancies and five Dry Januarys notwithstanding, I had drunk alcohol every week since I was a teenager. I could stop at one glass, but usually wanted more.

As a mother of two children, now aged 13 and 11, I saw wine as an essential antidote to the hard graft of parenting — often drinking half a bottle after a hard day. During lockdown, my drinking increased to the extent that I even taught my then 11-year-old daughter how to make my daiquiris.

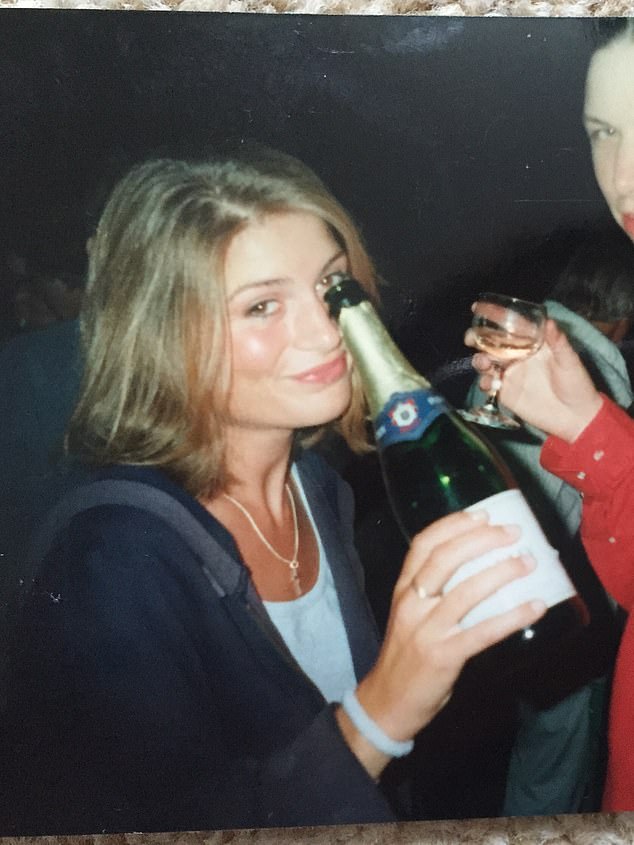

Antonia enjoying a drink in her 20s. For much of her adult life alcohol was part of her identity, turning her into ‘fun Toni’ at parties and helping her switch off after a stressful day, she writes

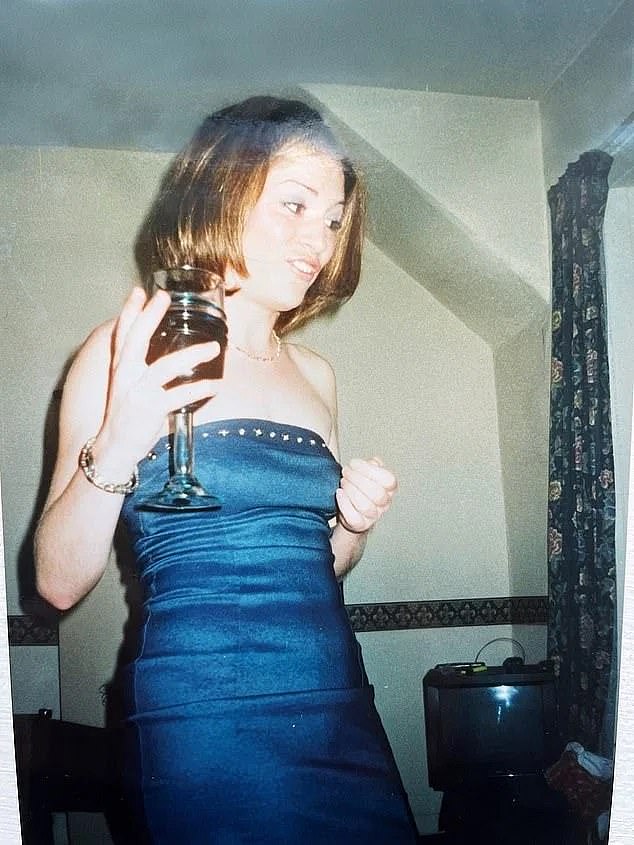

Antonia at university. During Dry January in 2022 she signed up for online sobriety school Monument, which teaches that alcohol is the culprit rather than the person drinking it

I drank more than the recommended 14 units a week, but, I reassured myself, no more than many fortysomething women. Though aspects of my drinking were problematic I did not, as far as every popular metric around drinking was concerned, have a problem.

Increasingly, however, hangovers left me racked with anxiety over what I might have said or done wrong. After a particularly boozy Christmas in 2021, I wondered if life would feel easier without alcohol.

Halfway through Dry January 2022, I decided to quit for longer, signing up to Monument, an online sobriety school. Unlike AA, which maintains alcoholism is a disease that can never be cured, Monument believes alcohol abuse is a spectrum and that alcohol — addictive to everyone — is the culprit, rather than the person drinking it.

As months passed, I saw alcohol in an increasingly sinister light. Yes, much of my drinking had seemed harmless, but it had also been behind every traumatic event in my life: from fracturing my wrist as a student to getting sacked from my first job during work drinks. It had also stopped me developing healthy coping strategies for difficult situations. Meeting new friends or dating? The easy, instant solution became drink.

Yet stopping was easier than I expected, even at events — birthdays, a wedding, two funerals — where our instinctive reaction is often to drink.

Sober, I read voraciously, my productivity soared and my skin glowed. I felt braver, kinder, capable of making small talk at parties without the social lubrication of alcohol.

My husband, who has always been a moderate drinker who can take or leave alcohol, was pleased — he’d always thought I was happier not drinking — and my children happy they had more of my attention.

Yet privately, a part of me also felt embarrassed. I hadn’t hit rock bottom, crashed my car or streaked naked while drunk. I was just a midlife mum who liked wine a bit too much. Was stopping drinking entirely a tad melodramatic? An attention-seeking ploy?

My friends, most of them enthusiastic drinkers, were supportive but surprised by my all-or-nothing drinking strategy. Yet as an all-or-nothing person, I was convinced if I had one glass, I’d want another — and I’d soon be back to a life where weekends without wine seemed inconceivable.

I marked a year alcohol-free with mixed emotions — making a big deal out of it felt fraudulent.

Towards the end of last year Antonia admitted to herself that she missed drinking, saying she lacked alcohol’s licence for stupidity and relief in a serious adult world

To stay motivated, I knew I needed further goals to aspire to. Yet, slowly, my good intentions unravelled.

I signed up to a novel-writing course but dropped out halfway through. I couldn’t conquer the wine-avoiding chocolate habit that had seen me gain half a stone. Meanwhile, my social media use soared as I tried to get the missing dopamine hit from likes and comments. Instead, constantly comparing myself to others made me feel anxious and depleted.

In short, sobriety no longer seemed transformational — after gaining in confidence during the first year, the benefits had plateaued and I began to feel bored.

Towards the end of last year, I admitted to myself I missed drinking. Not for its stress-relieving properties — I’d learned that if you simply sit with difficult emotions, they will pass. What I lacked was alcohol’s licence for stupidity and relief in a serious adult world.

Nobody had treated me like an outsider but, increasingly, I felt like one.

Sobriety influencers suggest we ditch heavy-drinking friends and seek support networks among non-drinkers. But I loved my friends, and at 45 had neither the time nor energy to find new ones.

I struggled to shake a gnawing sense of otherness: on the sidelines of my son’s football match as parents anticipated their lunchtime pint; at the mulled wine table outside the school Christingle service; and when a friend’s face dropped when she realised the bottle of Prosecco I’d turned up with was non-alcoholic.

So in early January, ahead of a reunion, I told my three university friends that I would be drinking. They said they loved me drunk or sober but jumped to get a second bottle of Prosecco when I arrived.

Chris was apprehensive. He had supported me more than anyone in my decision not to drink. But my heart hammered with excitement and trepidation.

I expected the Prosecco to taste disgusting — as alcohol does to a teenager — but the bubbles sparkled deliciously on my tongue. I felt overwhelmed and tearful that, at least, I had finally made my decision.

A few sips later and I felt a familiar sense of giddiness. I had planned to stop after one glass — a new ground rule, along with not drinking at home or in response to stress. But the detachment from being slightly drunk, and delight at being with friends, rendered rules ridiculous. I drank another glass and a half of white wine over lunch.

For a few hours, I felt blissfully removed from the outside world. It was only as the effects wore off that I wondered what alcohol actually contributed to the occasion. An illusion of joy, undoubtedly. But were my conversations more meaningful as a result? Was my laughter more heartfelt?

I expected the Prosecco to taste disgusting — as alcohol does to a teenager — but the bubbles sparkled deliciously on my tongue

I wasn’t sure.

My husband was relieved I seemed lucid on my return. But I woke at 5am with a dry mouth and sense of unidentified panic — a reaction to the alcohol, undoubtedly, but perhaps guilt at starting drinking again, too.

I’d forgotten how deeply unpleasant I am with a hangover. Groggy and irritated, I snapped at my daughter for making a mess icing cakes and couldn’t muster enthusiasm for my son’s football match. The children didn’t say anything, but I felt a terrible mother.

Alcohol can be detected on the breath for up to 14 hours after a drink, but I believe it affected me for the rest of the week.

Seven days later, friends were incredulous when I said I was still too hungover to drink again. While the effects may have been psychological, research shows that after a long period of abstinence, our functional tolerance (the ability to withstand impairments such as slurred speech) and metabolic tolerance (the rate at which the liver eliminates alcohol from the body) reduces.

My children had been so proud of me for not drinking that I was too ashamed to tell them I’d started again. They found out a fortnight later, through my daughter’s friend, after I wrote about it on Instagram. Yet I was surprised by their mostly sympathetic reaction.

‘I just don’t think after two years you’re going to get drunk any more,’ my daughter reassured me — and I realised she might be right. It was the permission I had given myself to drink, more than the drink itself, that I had found liberating.

It was nearly a month before I drank again at a pub with friends. As soon as the Sauvignon Blanc hit my empty stomach, my inhibitions were lowered, conversations seemed less guarded, more intimate… and, in truth, more fun. When my glass was finished (we were all driving), I felt a tangible sense of loss.

One glass, I realised, would probably never feel enough. Yet it was enough to make me wake at 5am, feeling miserable. I also believe alcohol made me more emotional and less resilient that week. I flew off the handle when Chris forgot to get the firewood and cried during an episode of Friends.

I wondered if, for moderate drinkers, a long period of abstinence could act as a circuit-breaker — rewiring the brain to consume less. If so, it was a huge relief I appeared to be one of them.

Yet even drinking a glass or two sporadically over a period of weeks, I noticed my skin looked more lined, spots appeared around my nose and chin, and my sleep, even on nights I wasn’t drinking, was disrupted. To assuage my guilt, I exercised harder, braved howling gales to run when injury allowed and spent 45 minutes instead of 30 on my exercise bike. I turned down crisps to compensate for the calories in wine and ate less chocolate. I lost 5lb, but it was a pyrrhic victory.

But I was also curious to know if the sense of abandon being drunk once provided, and that I used to crave, still held the same appeal. Hence this weekend’s dinner party. ‘I might start swearing,’ I warned the other guests.

‘I haven’t seen drunk Toni for so long,’ one friend said excitedly; another told me I was ‘sparkling’. Though I wanted my sober self to be enough, I was quietly thrilled by the compliment.

My memories began to blur after four glasses of champagne, and by 9pm, when I had moved on to Sancerre, I was slurring my words. My husband says I’m more interesting sober, ‘because you’re repeating yourself endlessly when drunk’. Nevertheless, I was overcome with affection for him — hence the out-of-character hearts across the table.

The freedom from the pandemonium of my midlife thoughts — work, children, chores, repeat — is welcome.

Of course, it comes at a cost. By the taxi ride home I was hiccupping, and I woke with a jolt at 4.27am, with a sense of self-loathing that lingered 48 hours on.

As I type, I’m wondering whether my behaviour towards my hostess warrants an apology, and vow not to get that drunk again.

‘So, was it worth it?’ a fellow guest WhatsApps me.

To which I say, I just don’t know. While I don’t think I’ll ever get that drunk again, an all-out ban isn’t on the cards either. A life of total sobriety no longer appeals.