Press play to listen to this article

RIGA — If you want to get an abortion in Poland, Kinga Jelinska is happy to help.

Legally terminating your pregnancy is almost impossible in the Eastern European country. Abortion is only allowed in the case of rape or incest, or when it threatens the life of the woman.

That’s where Jelinska comes in. She’s the co-founder and executive director of Women Help Women, an Amsterdam-based nonprofit that helps provide women with the pills needed for an at-home medical abortion. The service Jelinska’s group provides falls into a legal grey zone; self-induced abortion is illegal in a number of countries, but in Poland, it’s not explicitly banned.

The Polish activist is outspoken about her opinion that every woman should have the right to make her own decision whether to continue with their pregnancy.

“We do not have patience anymore,” she said, addressing a room full of abortion providers and researchers on a crisp September morning in the Latvian capital of Riga. “We are already in a revolutionary moment.”

Speaking from the podium of Riga’s Stradiņš University at a conference held every two years on abortion access, Jelinska addressed a friendly audience: Everyone in the room believed in a woman’s right to terminate their pregnancy. But Jelinska struck a more urgent tone than many other speakers, describing the situation for Polish women as “dystopian.”

While men in Poland have easy, cheap, over-the-counter access to erectile dysfunction medication like Viagra — which she noted has even been turned into flavored chewing gum — women are prevented from accessing the pills that can stop a pregnancy.

“Where is my candy shop for abortion?” she said. Abortion pills, she demanded, should “be as available as vitamin C.”

At a time when the right to abortion in Europe and the U.S. is once again the subject of heated debate, Jelinska is part of a small but growing network of women who have made it their mission to wrestle abortion from a decision made by lawmakers and society at large, to put mifepristone and misoprostol, the two pills that together are needed to carry out a medical abortion, in the hands of anyone who wants them.

In countries where abortion is legal, the activists work openly, registering nonprofits and setting up small offices run by a handful of staff. Where abortion is banned, they work clandestinely. In Poland, a member of the network, Justyna Wydrzyńska, is facing trial for providing a woman with the pills needed for an abortion.

The activists face opposition in the form of well-funded anti-abortion campaigners who are also expanding their presence in Europe, supported by the conservative Christian establishment led by the Roman Catholic church. Their full-on advocacy of abortion on demand doesn’t always sit well with those who say it should be a last, and not a first, resort.

But new attention on the issue — especially in the wake of the Dobbs decisions in the United States, striking down Roe v. Wade — has coincided with a surge of support. In this in-depth investigation, reporters from POLITICO, WELT and Newsweek Polska reveal how a network sometimes referred to as abortion’s underground railroad is operating in an increasingly hostile environment, even as new funds allow them to expand their activities.

American origins

The origins of the movement can be traced to the U.S., where a network of NGOs working to secure access to abortions long predates the recent Supreme Court decision. Access to abortion in the U.S. has always been uneven, subject to a constantly changing patchwork of differing state-level laws and regulations. Between the landmark Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 and the Dobbs decision this June, U.S. states had enacted 1,381 separate abortion restrictions. .

And just because abortion was legal in any given state, it didn’t mean it was easy for women to access the procedure: In many cases, whether in Republican-leaning states with tighter restrictions or rural areas lacking an infrastructure of providers, finding an abortion was difficult and costly.

In the early 1990s, a range of abortion nonprofits began to fill that gap, offering to pay for a woman to get an abortion and, where necessary, travel to a state or city where they could receive it. The Women’s Reproductive Rights Assistance Project, or WRRAP, was founded in 1991 to offer financial assistance to those in need of abortion or emergency contraception; the National Network of Abortion Funds followed in 1993.

Organizations like WRRAP and NNAF have grown steadily over time and, like other nonprofits working in the abortion space, have seen their funding skyrocket in recent years.

The use of pills to provide abortions in places where it’s restricted, however, was pioneered by the Dutch doctor Rebecca Gomperts, who in 2005 created Women on Web to help women access abortion medications by mail. Since then, a proliferation of similar groups, both in the U.S. and Europe, have sprung up, investing their time — and sometimes risking their freedom — to provide access to abortion wherever it is wanted.

Elisa Wells is the co-director of Plan C, which provides information about medical abortions and conducts research on abortion pills. She said she and the others who founded the organization in the mid-2010s were inspired by how accessible medical abortions were in other parts of the world and vowed to bring that ease of access to the U.S.

The COVID pandemic pushed things further. With telemedicine being approved in more and more states, new organizations cropped up to meet the demand for at-home abortions. From Abortion on Demand, to Hey Jane, to Choix, to Just the Pill, a constellation of new options have been created in just the last two years.

“I think we were heading in that direction just because of more intense [abortion] restrictions that were just passing all over the United States,” said Julie Amaon, medical director for Just the Pill, which operates in four states and seeks to reach people in rural areas. “But I also think COVID escalated that hugely.”

In the wake of the pandemic and the growth of these organizations, use of medical abortion has grown swiftly in the U.S.: In 2020, the Guttmacher Institute estimated that medical abortions accounted for 54 percent of all abortions in the U.S., a significant jump from 39 percent in 2017.

European network

In Europe, the groups helping women with abortions operate as a loosely affiliated network, swapping tips and sometimes personnel across borders, much like the pills they supply by mail.

Mara Clarke heads the Abortion Support Network (ASN) which is based in the United Kingdom and operates throughout Europe. It provides women with information as well as funding to travel and pay for surgical abortions in the U.K., which allows abortion in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, one of the longest windows to receive an abortion in Europe. She got her start in the U.S after she read about women being forced to travel to New York City from around the country to receive an abortion. “That taught me that legal and accessible are two different things,” Clarke said.

She got involved with the Haven Coalition, one of nearly 100 organizations in the National Network for Abortion Funds, which works to increase access to abortion for low-income people; and when she moved to the U.K. a few years later, she brought the practice across the Atlantic, setting up the Abortion Support Network in 2009 to help women who couldn’t access abortions in Ireland.

She now works all over Europe, including in Poland through Abortion Without Borders, an umbrella group that also includes the Abortion Support Network and Jelinska’s Women Help Women. The group says that since the Polish Constitutional Tribunal introduced the strict rules limiting abortion two years ago, its helped nearly 80,000 women access abortion in the country.

It’s not a coincidence that much of the network’s energy is concentrated on Poland. The country is at once the place in Europe where activists face the most active and organized opposition, and a society undergoing rapid social change.

Jelinska, co-founder and executive director of Women Help Women, never had what she calls a “what-the-fuck moment” — “when you seek an abortion yourself and discover the oppression of you own body and start to think and reflect.” But she knows many others who have.

The 42-year-old mother of two twice used pills to abort when she was in her thirties, but only after she was already deeply involved in abortion activism.

“I knew that self-induced abortion with a pill is safe and that the side effects are mostly harmless,” she said. “I was in a privileged position. The abortions were simple non-events for me.”

When she was growing up in a middle-class family in Warsaw, however, abortion was taboo: “I grew up with a constant fear of getting pregnant, which also had an impact on the quality of my sexual life.”

This all changed in 2004, when she moved to Amsterdam. “I had a lot of friends who openly talked about their abortions. My best Dutch friend even told me about hers at the supermarket cashier. That was completely new to me,” Jelinska explained.

Being vocal about these issues comes with a price. Death threats are part of Jelinska’s daily life. “Of course, this affects me,” she said. But Jelinska sees no other way. “Sometimes it is necessary to disobey harmful laws,” she said.

How it works

The network’s activities are made possible with the widespread availability of cheap and safe pharmaceutical abortions, which have transformed how pregnancies are terminated. More than half of abortions in the U.K., for example, are now carried out at home.

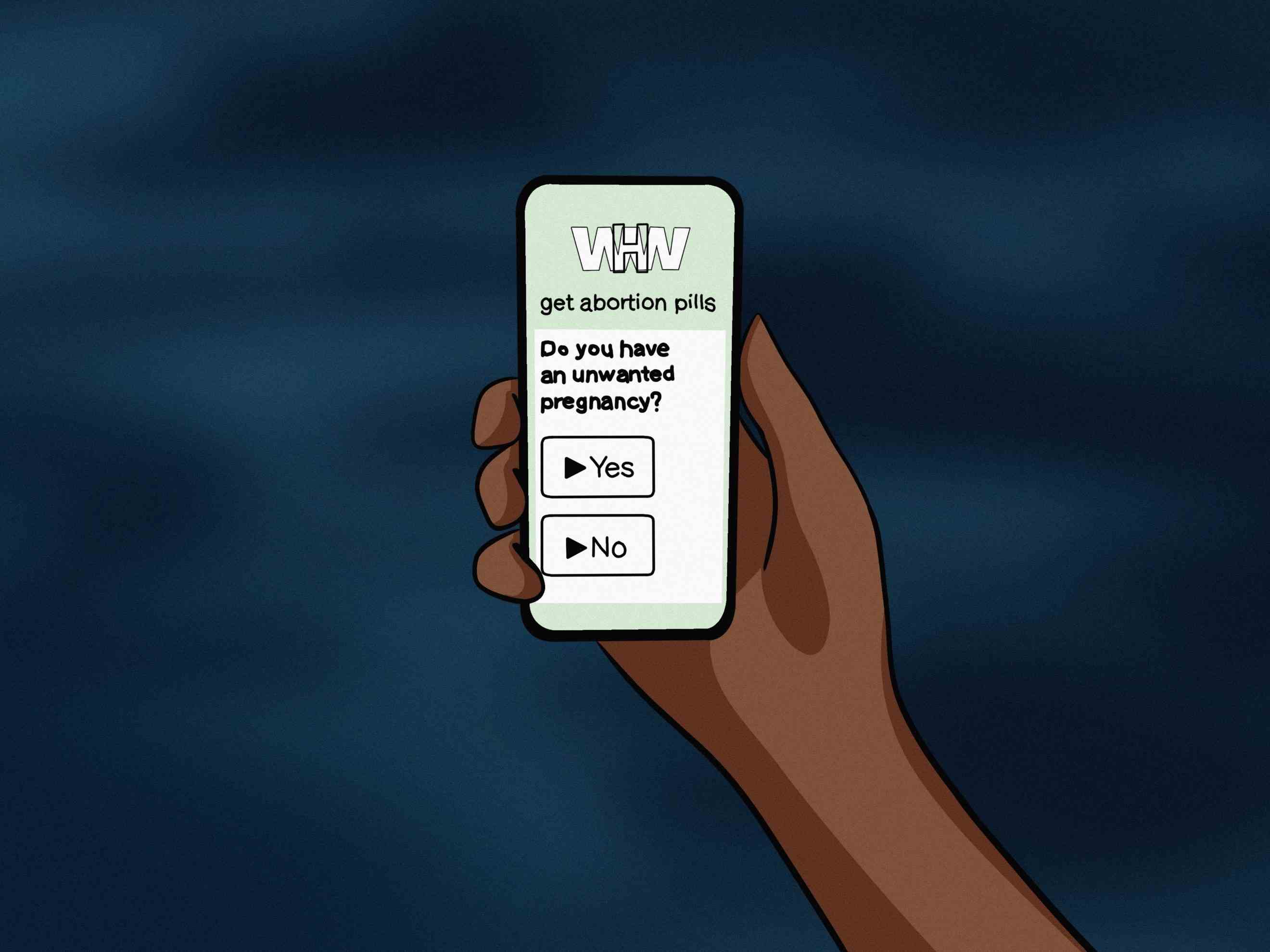

Jelinska’s Women Help Women and Gomperts’ Women on Web operate in similar ways.

Users fill out an online questionnaire answering questions about their pregnancy and their medical history. Venny Ala-Siurua, executive director of Women on Web, says the answers are reviewed by an international team of doctors — mainly working as volunteers. As long as medical criteria are met, doctors issue women a prescription.

Suppliers within Europe then ship the pills to the women who need them — including in countries where abortion is restricted, such as Poland or Malta. The women who receive the pills provide a voluntary donation for the service.

Two drugs, mifepristone and misoprostol, are usually taken to induce an abortion. First mifepristone is taken orally. It blocks the pregnancy hormone progesterone, causing the uterus lining to thin out. This stops the embryo from latching onto the walls of the uterus and keeps it from growing. Misoprostol is taken next, either vaginally, or orally. It causes cramping, ending the pregnancy.

Both drugs are on the WHO’s list of essential medicines. And according to the global health authority, they’re very safe. The number of deaths linked to mifepristone are exceedingly rare (at 0.0006 percent of users). Complications from the pills are uncommon — making up less than 1 percent of cases at the top end of the estimates. They’re also cheap, with a retail price of between $3.75 and $11.75 for both together.

After the first trimester of pregnancy, using abortion pills is no longer recommended. Women in countries where laws are restrictive may then travel abroad for a surgical abortion.

Illustrations by Dato Parulava for POLITICO

The groups don’t make public the identities and whereabouts of the doctors and suppliers of misoprostol and mifepristone, but Ala-Siurua says that sourcing the drugs is fairly straightforward. Misoprostol is easy to get hold of because it is a widely used stomach medicine. Mifepristone is more difficult because it requires a prescription, but in general it’s not hard to get from the many approved suppliers throughout the European Union.

Speaking on the legality of the operation, the executive director said that the service was “tailored” based on the location of the person requesting help. In Europe, for example, they used European doctors prescribing medicines registered in the EU for legal reasons.

“You can procure abortion drugs in many countries. Especially if it’s a prescription drug for your own personal use, you’re not breaking the law,” she said. In the case of Poland, she noted that a self-administered abortion is not illegal. “We take the calculated risk that we think we can take, and there’s no risks for the person,” she added.

Ala-Siurua explained that the difficulties faced by her organization are surprisingly banal. A change in the Google search algorithm meant that its website, which before usually appeared in the top three search results for searches like “abortion pills,” was bumped down.

For a while, it appeared on page six of the results, and traffic to the website plummeted. “There’s no doubt” that women who needed abortions went without because of the algorithm change, she said. She is working to improve the website’s search optimization and traffic is slowly recovering. But it’s still well below its previous peak.

Surging support

The Dobbs decision in the U.S. may have overturned 50 years of precedence in the country, but by raising attention on the issue, it has also galvanized interest in, and funding for, the organizations providing abortions.

Like the U.S., Europe is experiencing a renewed push against abortions, especially in Poland but also in places like Italy, where conservatives and the far right have sought to limit access to the procedure. “We assume that each country is one election away from the tightening of regulations,” said Clarke, of the Abortion Support Network.

On the flip side, each time there’s a dramatic fight over abortion rights, whether it’s in Ireland, Poland or the U.S., Clarke’s organization receives more money and attention. A review of these groups’ finances reveals an unmistakable trend: more funds flowing into them with each passing year.

According to its 2020 financial statement, the Abortion Support Network’s funding increased by nearly 40 percent, year-on-year, to £364,616. While the figures aren’t public yet, Clarke said that backing in 2021 topped £400,000. She’s expecting to raise more than half a million pounds this year.

Ciocia Basia (“Auntie Basia”), which helps women from countries where abortion is illegal to have one in Berlin, also noted a steady increase in donations since it was founded in 2014. In 2019, the group received €16,000. In 2020, after the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruling on abortion, it received €40,000. Since 2021, it has raised €24,000 through a GoFundMe campaign.

Donations from private individuals make up the bulk of the support to the mostly volunteer-run outfits. These range from €5 or €10 all the way to more substantial donations of thousands of euros. Gomperts’ Women on Waves is aiming to raise half a million euros through crowdfunding for a clinical trial to test mifepristone as a general contraceptive, like the more common contraceptive pill.

Larger charitable foundations are getting involved as well. The Open Society Foundations, a charity network backed by philanthropist George Soros, donated $447,000 to Women Help Women in 2021 — almost twice as much as it did in 2020 ($260,000). It has also backed Plan C, the U.S.-based nonprofit.

It’s not just private donors lending their support. The French government announced earlier this year that it will pledge €60,000 to Abortion Without Borders, to help Ukrainian refugees get abortions. The Belgian government donated €10,000 to the same group last year, and another €20,000 this year.

The trial of Justyna Wydrzyńska

Not everybody is pleased by the network’s activities. The flow of misoprostol and mifepristone around the world relies on governments accepting medical abortion — or at least turning a blind eye to it. Poland offers an example of what a crackdown looks like, and it could be a roadmap for the U.S., especially if the anti-abortion Republican Party wins the upcoming midterm congressional elections.

At the conference in Riga, where Jelinska joked about popping abortion pills like candy, conference-goers were offered to take a picture behind a cardboard cutout of Justyna Wydrzyńska, the Polish activist facing trial for having helped provide a woman an abortion.

As Jelinska delivered her impassioned speech on the stage that day, she paused and nodded to Wydrzyńska, who sat in the front row. The audience applauded.

“Soon she might sit somewhere else: in prison,” Jelinska said, adding that “it seems that, right now, half of the world thinks abortion pills are a tool of crime.”

Wydrzyńska has been involved in abortion activism for more than 15 years — she organized the country’s first online forum where Poles could exchange information on how to get a safe abortion. In Poland, together with Jelinska and other activists, she founded the Abortion Dream Team, an organization providing women with advice on abortions.

In 2018, the Abortion Dream Team activists appeared together on the cover of Wysokie Obcasy, a weekend supplement to the national daily Gazeta Wyborcza. The inscription “Abortion is OK” on their shirts divided even liberal commentators.

Today, Wydrzyńska is waiting for the next hearing of her trial, scheduled for January 11. She faces up to three years in prison for helping with a medication abortion. “We will not let that happen,” says Abortion Support Network’s Clarke, sitting with Wydrzyńska on a recent visit to the Abortion Dream Team’s office in central Warsaw. They’ve known each other for years.

Despite the strict rules against abortion provision, it is not illegal for a woman to terminate her own pregnancy — Polish women cannot be arrested or charged for procuring or taking abortion pills. Only help is sanctioned — and that’s what Wydrzyńska stands accused of.

The woman to whom Wydrzyńska provided abortion pills to was Ania — a mother who had been a victim of domestic violence. According to Wydrzyńska, the woman had previously tried to travel to Germany for the procedure but was prevented from doing so by her husband. She ordered tablets but worried they might not be delivered in time. Wydrzyńska decided to give her the pills she had for her own use. Then Ania’s husband informed the police.

‘Time is key’

The trial has pitted the Wydrzyńska and Jelinska’s network of abortion activists against Poland’s opponents of the procedure — most notably Ordo Iuris, an arch-conservative Roman Catholic organization that is close to the ruling Law and Justice party and has been working for years to tighten Poland’s abortion law.

Magdalena Majkowska, a member of the board of Ordo Iuris, has argued that the compounds like mifepristone and misoprostol are not approved in Poland for abortion.

According to Katarzyna Gęsiak, the director of the Ordo Iuris Center for Medical Law and Bioethics, the use of self-administered abortion pills — beyond constituting a risk for women’s health — also “leads to the death of a human being.”

Moreover, said Gęsiak, helping women access the pills violates Polish law: “According to the law, the child’s mother is not criminally liable, but the persons providing her assistance do … This is the right solution, and this crime should be prosecuted like any other offense.”

The president of Ordo Iuris, Jerzy Kwaśniewski appeared at Wydrzyńska’s first hearing in July.

“One of us thanked him for giving the case additional publicity,” said Wydrzyńska. But she admits that testifying has been emotionally difficult. In court, she recalled how she experienced domestic violence years ago and spoke about her own abortion. “I had my abortion at 12 weeks and I have also been in an abusive relationship. I know what it means to be in this situation. Helping her was my first human response,” the activist said after a recent trial hearing.

Both Clarke and Wydrzyńska say they’re glad that the case has generated international media coverage. They want to draw attention to women from other countries where access to medical abortion is still difficult. The group is also launching a campaign #IamJustyna to raise awareness of the situation in Poland.

But with attention on their activities growing, they know that the pendulum could rapidly swing the other way.

“Unfortunately, anti-abortion organizations are very effective and creative,” said Wydrzyńska. “A few years ago, Ordo Iuris prepared a special manual for customs officials to help them intercept pills from abroad. They knew very well that in the case of medical abortion, time is the key.”

Jelinska agrees. “There is only the present: it matters the most,” she said. “Not abortion once upon a time, not abortion sometime in the future, but abortion right now, for certain and for real.”