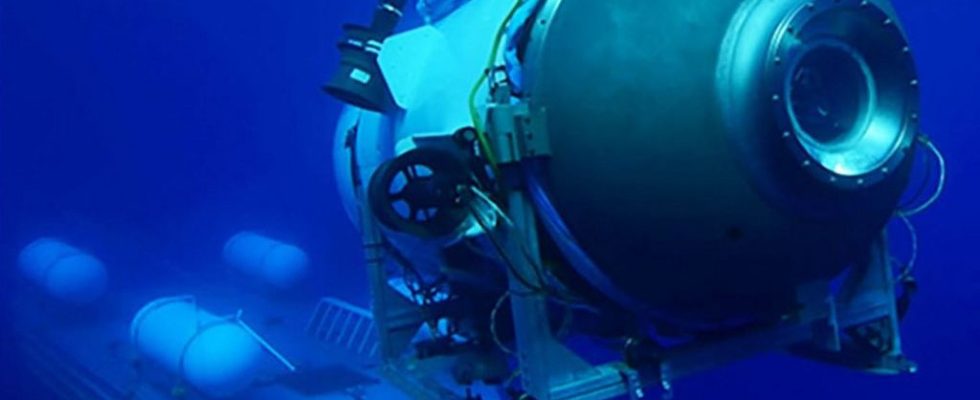

The drama of Titanthe submarine missing since Sunday as it set out to explore the wreckage of the titanic, has shed light on a still little-known activity: deep-sea tourism. On the fringes of mass travel, going by submarine remains a rare activity – count 18 expeditions to explore the titanic planned for the summer of 2023 by the American company OceanGate Expeditions – which owns the Titan – , all obviously questioned for a few days.

Why such a rarity? Firstly because of the price, which is rather prohibitive. With OceanGate Expeditions, it’s 228,000 euros per passenger (250,000 dollars), for eight days under the sea. sailor “is an anecdotal activity”. “It shows the search for the experience ”never done by others”. Some go to space, others climb Everest, others explore the ruins of titanic. An activity of very wealthy people in search of adventures that few can afford. » In an interview with New York Timesthe president of OceanGate Expeditions, Stockton Rush, himself made a parallel between his company and Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic and SpaceX, pillars of space tourism.

A tourism that constantly pushes the limits

It’s because the tourist industry “keeps pushing the limits and going ever further into unexplored territories”, continues Note Chaouini, doctor in information and communication sciences and tourism specialist. “With the rise of mass tourism, more and more accessible, the ultra-rich seek to differentiate themselves, sensations unknown to the general public. »

But it’s not just the cost of the passenger ticket that is extremely expensive. The expedition itself is also extremely expensive, notes Nawel Chaouini: “Few companies can afford to finance this kind of action. The proof is that the seabed is still very mysterious for Man. Only 5% have been explored, even though they cover 70% of the planet. The idea is widespread in the scientific community: we know the surface of the Moon or Mars better than the bottom of the seas.

Essential funding for research

This is one of the reasons for the – relative – growth of this underwater tourism: it helps finance expeditions. “Ultra-rich tourism offers unexpected sources of income for very costly and not necessarily profitable research. The same goes for the development of space tourism – it is becoming economically vital for scientists”, analyzes Nawel Chaouini.

THE Titan includes five passengers: a pilot, three tourists but also a scientist, Paul-Henri Nargeolet, ambassador of the Cité de la Mer in Cherbourg. The OceanGate Expeditions website also mixes genres and indicates that the company “builds 5-seater submarines dedicated to scientific research and tourism”.

How far is the limit?

Contacted by 20 minutes, the Cité de la Mer of Cherbourg explains that it does not want to comment on the economic aspect of these underwater expeditions. And specifies: “Paul-Henri Nargeolet benefited from tourist dives to make scientific surveys and continue to perfect habitable devices for science. It’s an anti-business that lives science to the full. »

It is therefore a collaboration willy-nilly, between scientific research lacking funding and ultra-rich tourism lacking sensation, an alliance as unnatural as it is essential for the scientific community. But not without risk, concludes Nawel Chaouini: “We must be careful that the search for adrenaline of the ultra-rich, or the search for corporate profits, does not lead to increasingly risky expeditions that go beyond the rules. of caution. »

According to New York Times, a former OceanGate employee, David Lochridge, was fired five years ago after expressing doubts about the device. He considered in particular that the porthole of the submarine was only certified for a depth of 1,300 meters, that is to say three times less than the depth where the titanic. During his trial, he had warned “of the potential dangers for the passengers of the Titan when the submersible reaches extreme depths”. The drama of Titan – for whom the hope of a happy outcome dwindles hour by hour – could therefore put a spotlight on the limits of a tourism that hoped to free itself from them.