When Fridtjof Nansen returned from his polar expedition from 1893 to ’96, he wrote about the huge floating mountains that had enclosed his ship, the Frams: “Unseen and untrodden, the frozen polar regions slumbered beneath their immaculate, eternal ice mantle from Beginning of the times. ” Of course, Nansen had never heard of global warming phases, let alone the Paleocene / Eocene Temperature Maximum (PETM) around 55.8 million years ago. We now know that there was no ice anywhere on earth during the PETM, and that the sea level was around 70 meters higher than today.

In other words: The topos of the “eternal ice” has long been refuted by the geosciences; today it is melting at an impressive pace in front of all of us. The air in the Arctic is warming more than twice as fast as anywhere else on the planet. Nansen’s “mighty solidified” north polar ice has shrunk by 80 percent of its volume compared to 1979.

And with that we switch to the other side of the planet, to Antarctica. From there you always hear when a large iceberg breaks off again: This year, the A76, with 4320 square kilometers, is currently the largest iceberg in the world (Mallorca is 700 square kilometers smaller). In 2017, the A68 was even larger at 6,000 square kilometers; the record has so far been held by the B15, an approximately 11,000 square kilometer table iceberg that broke away from the Ross Ice Shelf in 2000.

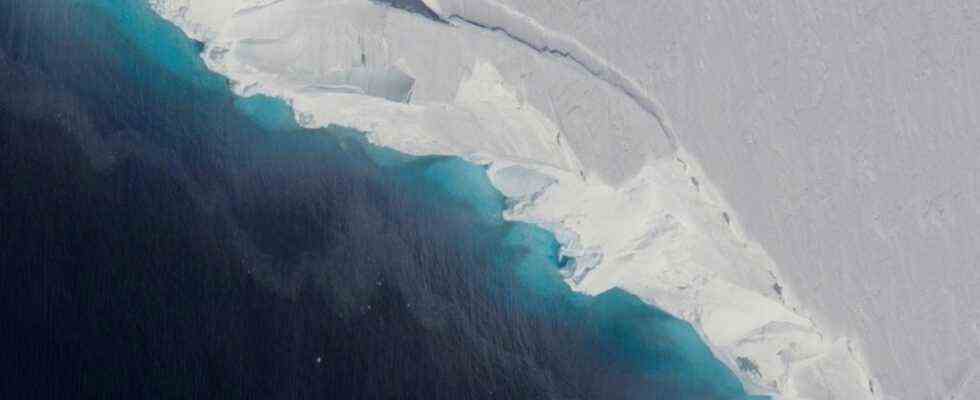

But all of this is nothing compared to what is now threatening. Most of the glaciers in Antarctica slide dozens to hundreds of kilometers across the coastline into the open ocean. If the ice hits shallows, submarine rock islands or rock ridges, the slow glacier flow is also slowed down on the mainland by the backwater effect. This is also the case with the huge Thwaites Glacier, whose ice shelf area alone is twice the size of Belgium. As my colleague Angelika Jung-Hüttl reports, this 600-meter-thick ice surface threatens to burst in the near future. Reason: The ice shelf is washed under by warm water and thus continuously melted from below.

That is not good news in itself, but the consequences are even worse: The ice shelf has so far acted like a retaining dam for the giant glacier pushing in from the mainland, which would flow even faster into the sea after the ice shelf “cork” burst. This is one of the reasons why the Thwaites Glacier is often called “Doomsday Glacier”.

Colleagues from the New York Times have programmed such an impressive visualization of the Antarctic glacier structures and the Antarctic circumpolar current (which is also changing dramatically) that I absolutely have to give you these animations wanted to show. One then thinks half fascistically, half resignedly: We can still visualize and analyze the most geographically remote consequences of climate change so impressively. We just can’t seem to stop the whole thing anymore.

I hope, despite this icy and gloomy topic, I can wish you happy holidays, if not a white Christmas for the time being. Our newsletter takes a two-week break. I myself am saying goodbye to a longer sabbatical, but all my colleagues will continue in January where I have stopped now, with climate change and its consequences.

(This text is from the weekly Newsletter Environmental Friday you here free of charge can order.)