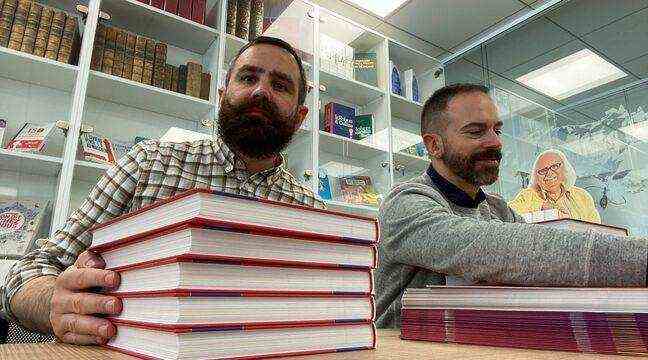

Gastronomy is an institution in France and the words to speak of it have a history almost as tasty as the dishes they accompany. This is what we learn in the book by Mathieu Avanzi and Jean Mathat-Christol

“As we dine at home”, published this Thursday, October 28 by Le Robert editions. The first is a linguist, author of “Comme on dit chez nous” and the second teaches cooking and baking. On the territory of the Metropolis and in Corsica (and not in the overseas territories for lack of data), they offer a culinary journey which has the merit of defeating certain clichés on regionalism.

We learn that the development of regional cuisine is relatively recent?

Yes, it spread with the democratization of paid holidays and the expansion of fairs. These have existed since the Middle Ages but with the development of transport, they have spread and everything has been done for a deregionalisation of regional cuisine. The creation of restaurants (in the middle of the 19th century) also contributed to its diffusion.

Behind this craze, there is also the marketing argument because the region sells. From the 1980s, we wanted to diversify the food in supermarkets, helped in particular by progress on packaging. While in the 19th and 20th centuries, farmers simply ate a piece of cheese on potatoes, and even 30 years ago no one knew what raclette was (outside of Switzerland and Switzerland). Savoie), today you can find them frozen at Picard!

The name of certain specialties suggests that they are linked to a region, while not necessarily. Explain to us.

Beef Bourguignon exists as a specialty because that’s how it was sold in Paris. You had a whole series of meats in sauce with wine (Provencal stew, blanquette etc.) and it’s just a variation. Burgundy has taken over this specialty and erected it as a national monument, but ultimately the recipe had to vary from one region to another. It’s the same with the gratin dauphinois. A whole bunch of specialties that are sold to us as local, are not. It’s a bit of a scam (laughs). The fondue is also not Savoyard but Swiss.

There aren’t really any iconic Parisian specialties in your book. How do you explain it?

Paris draws its personality from other regions: it is a kind of centrifuge that takes from others and does not create anything itself while being the center of France from a cultural point of view. Some words are starting to appear in Paris but very quickly they will be exported elsewhere due to incessant back and forths with the Province. From a linguistic and gastronomic point of view, there is no imprint of Parisian culture. The section devoted to Île-de-France was therefore not very easy to complete even if there is indeed the croque-monsieur and the currant bread. There is also the fries which is Parisian but which the Belgians have taken back like a trophy. The French fries merchants quickly disappeared in Paris, and the fries were exported to Belgium with the first fairs. Today it is associated with Belgium because it has continued to develop it.

We see that the culinary vocabulary of Alsace, influenced by its proximity to Germany, stands out compared to those of other regions.

Yes, we see it with the example of the kebab, a specialty that developed in the 1980s. It is called a Greek in the Paris region, a kebab almost everywhere else except in Alsace where it is called Döner. And when we look at the tarte flambée (or flambékueche) this is a very strong example of deregionalisation. 20 or 30 years ago, we did not know what a flamekueche was. Now, the term has spread everywhere but Alsace is the only one to call it a tarte flambée, keen to distance itself, at certain times, from what comes from Germany.

On the terms used to designate carnival pastries, the book refers to twenty. Why so much diversity?

Yes and it is very difficult to make their inventory, it is missing in our book. This is one of the recipes for which there are the most variations: atria, bugnes, wonders, carnival donuts, bottereaux etc. If you extend it to Italy or Spain, there are also specialties based on fried pasta of this type, Shrove Tuesday being the last day when we could eat fat because after we entered the Lent.

We say Wonders in the South-West but also in French-speaking Switzerland so we imagine that these were previously connected areas. We should have said wonders throughout the south of France, there is a bugne variant that emerged in Lyon and an atrium variant that emerged in Montpellier or Marseille and which locally replaced the term wonders, which has been maintained in the outskirts. Often there is a lack of data to explain when variations occur.

Can we say that gastronomy is a breeding ground for new words?

In a dictionary like Le Robert, gastronomy, with technology for example, is one of the main sections where new words enter the language every year. A word like tartiflette which was regional twenty years ago is no longer so at all today. As soon as a word passes in the dictionary, it enters standard French and this is true for regional but also international gastronomy (wasabi, wok for example have been introduced recently.) Thus, many regionalisms well integrated into the language French came from Italian cuisine (spaghetti, lasagna etc.) and things are changing very, very quickly.