Despite the exuberance of arias and the tension in the plot, Mozart’s opera “Don Giovanni” is one thing above all else: a treatise on human sexuality between the primordial, violent instinct and the civilized variant of seduction and coquetry, passion and empathy. The stage drama does not offer a one-sided pamphlet-like statement, it does not even evaluate, although the woman-devourer Don Giovanni goes to hell in the end to calm the peasant and aristocratic society. Joy arises in the circle of the disappointed, a morally contaminated joy that is nourished by the damage done to the other.

The protection of the general public is not even feigned as a motive for crime, in this the culture of debate differs little from many today. It is a timeless discourse that is part of the process of civilization. From the productions, but also from the musical direction of “Don Giovanni”, you can see the current state of the discussion culture. Until the 1970s, Don Giovanni was still seen as a real guy who never ignored a sword fight and no woman. A daredevil as the war generation idolized as a role model.

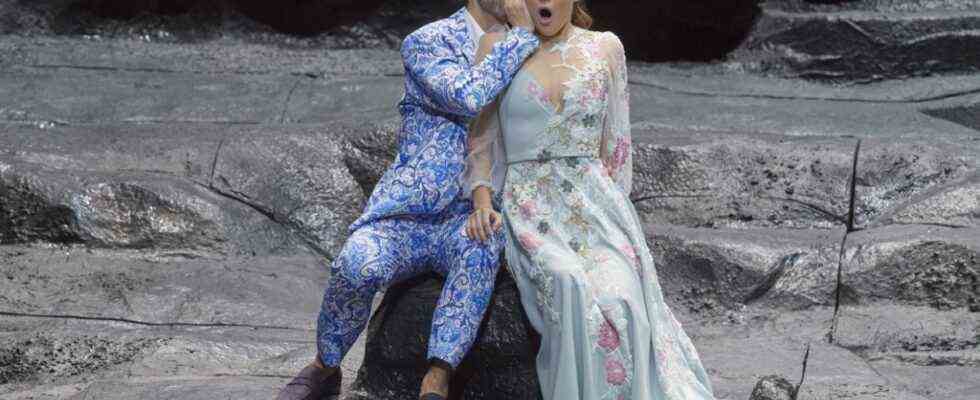

Director Barrie Kosky, artistic director of the Komische Oper Berlin and perhaps a little prematurely labeled as the highly talented joker of the opera business, has taken a different path with the new production of “Don Giovanni” at the Vienna State Opera. After the real social debates about sexuality and social morality have reached heated climaxes, Kosky withdraws from them with his staging and shows the opera as what it is at its core and perhaps should remain simple: a social parable in which the general human is concrete becomes inhuman, in which the handling of sexuality is symptomatic of the general way of dealing with one another, of frozen morals and the inability to communicate. The only one who communicates confidently and virtuously is Don Giovanni. That is why it is easy for him to seduce women, and Kyle Ketelsen embodies this type of self-confident bon vivant with virtuosity. Also largely vocally, although his well-fitting, deep baritone occasionally narrows in an ugly way, especially in the upper part.

Kosky concentrates on what he can do: sophisticated personal direction

If the sex baron hadn’t gone too far by trying to rape Donna Anna and stabbing her interfering father in a duel, then this man would have to be celebrated as the epitome of hearty joie de vivre. Even in the animalistic state he looks charming when he crouches with Leporello behind a rock and lurks like a lion for prey: “I smell the scent of women.” In many productions, this contradiction persists until the commander’s scene, which regularly fails, when the dead father appears as a spirit of vengeance and, as a speaking marble statue, chatters the libertine to death morally pissed off.

This danger does not even arise in the Viennese production. Kosky immerses the entire opera in a gray rocky landscape, in which even the happiest party scenes, which normally take place in the glamorously illuminated castle, are dimmed down to a carnival pounding in an apocalyptic mood. A production that gets by with such a boring stage setting for three hours without being boring is remarkable. One can only hope that this example will not catch on again, because, as a rule, such uniform images let the attention sink into the abyss.

Not so with Kosky, who concentrates on what he has mastered masterfully: a detailed, well-thought-out personal direction. Every performance is prepared and followed up, you can still hear the vanished shouting from the backdrop, nobody just stumbles across the stage, no acting movement serves itself. Besides, perhaps even before Kyle Ketelsen, it is above all Philippe Sly who vocalizes as Leporello and shines as an actor. Sometimes a bit awkward in the movements, but much more routine compared to the streaming premiere.

Live comes to life what worked badly in the stream premiere

Above all, this corona-related streaming premiere showed that opera only works very poorly on the screen. This not only affects the acoustics, but also the acting moment. You see a lot more precisely than necessary, but you rarely or never have the overall impression that you permanently have live and that only provides the frame of reference in which the individual action makes sense. One is forced to focus on the detail, on the narrow view, and, according to the composer’s intention, should only perceive the detail as a starting point for the greatest possible whole. Otherwise it would be all slapstick and not that subtle comedy that Mozart and his lyricist Da Ponte opposed to pure entertainment.

It is precisely in this that Mozart shows himself to be a true genius, and conductor Philippe Jordan, who has been music director of the house for a year, also strives for the right tempo, the right tone of voice from the first to the last bar, often getting into a somewhat stretched sense of time. apparently does not want to leave any note underexposed. Unfortunately at the expense of a dramatic, gripping forward thrust, but of course gorgeous in the slower lyrical arias. Patricia Nolz as Zerlina – with a more balanced mezzo-soprano than the sometimes sharp articulating Hanna-Elisabeth Müller as Donna Anna – shines here, as does Stanislas de Barbeyrac as Don Ottavio, a fantastic lyrical tenor in good moments who, in contrast to the stream premiere, shines live completely convinced and reveals the whole tragedy of the only selfless lover in this opera. He is mercilessly abused by Donna Anna, who presents herself as a pure victim.