It was a memorable moment curating the beginning of June next Documenta commissioned collective Ruangrupa At the beginning of December last year in Kassel the Cuban democracy initiative Instar the Arnold Bode Prize presented. A collective of curators honors a collective of activists. Does that fit the founder of the most important art exhibition in the world?

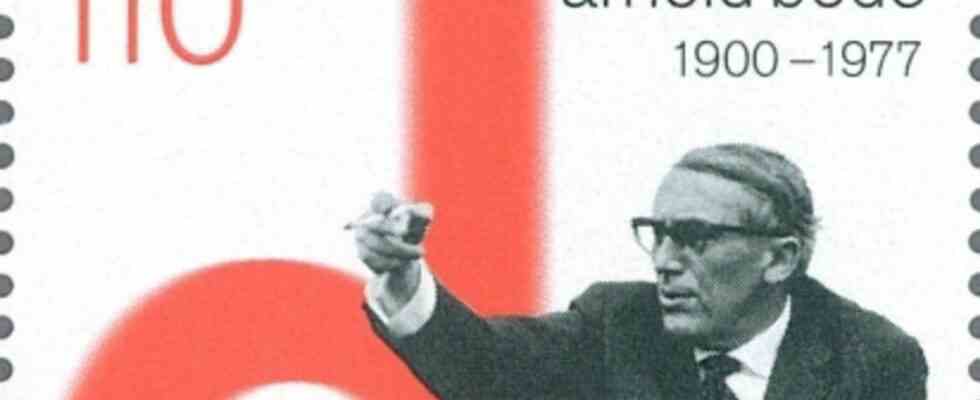

For Sylvia Stöbe, the painter, draftsman and room artist Arnold Bode, who was born in Kassel on December 23, 1900, was a brilliant individual. In the first biography of Bode that is now available, the Kassel architectural historian draws the picture of a restless art maniac, a sparkler of creative ideas burning from two sides.

Bode did not paint glass windows for Luftwaffe casinos during the Nazi era in Kassel

The habilitated architect, appropriately born in the Documenta year 1955, is not a theoretician. Obsessed with detail, without an art-historical superstructure or even literary ambitions, she traces Bode’s life from the Kassel art student, landscape painter and founder of the Kassel Secession to the director of the Berlin workshop for teachers of workshops, who was dismissed by the Nazis, to the interior designer of the post-war period and finally the larger than life father of the documenta, the 1977, one day after the end of Documenta 6, dies.

Her biographical scavenger hunt unearths interesting details. In 1951, Bode designed his first stand at the “Constructa” trade fair in Hanover. In 1952 he designed the plastic collection “Abstracta 54” for the Göppinger Plastik-Werke. The “Documenta” three years later was semantically in the air.

Sylvia Stöbe: Arnold Bode. artist and visionary. Founder of the Documenta – a biography. Euregioverlag, Kassel 2021. 118 pages, 87 illustrations, 18 euros.

With her mix of collage and research, Stöbe also relieves the man who, since the discovery of the Nazi involvement of his partner Werner Haftmann was also under suspicion. The accusation is that Bode did not paint glass windows for Luftwaffe casinos during the Nazi era in Kassel. “There is nothing wrong with Arnold Bode’s political views,” Stöbe sums up. However, his brother Paul, an architect, was a member of the NSDAP. The two later fell out. Stöbe dedicated a book to Paul Bode’s buildings in 2019.

However, what she clearly lacks in the new book is a view of the systemic nature of the Nazi continuities that converged in Kassel. She leaves unanswered the very gently tapped question as to whether Bode, whom she characterizes as an ardent social democrat and Bauhaus fan, as an avant-gardist and internationalist, never had any doubts himself as to whether he made a pact with the right people for his life project.

On the other hand, Stöbe succeeds in exposing her protagonist’s broad concept of art. Bode always thought of the Documenta as a transdisciplinary enterprise that included not only film, music, poetry and drama or “industrial form” but also “the urban”. Stöbe has printed Bode’s wonderful green, red and blue curled sketch of a “Documenta urbana” from the Documenta archive. The way the housing question is erupting again today, this concept, which has never been realized, suddenly seems red hot.

Anyone who also reads Bode’s forgotten quote in the commendable volume, “that art could also work off something of the utopia that is called better living, better living together”, will see Ruangrupa as a legitimate revenant of Bode’s idea of the documenta as an interdisciplinary work of art that should establish a new solidarity.