At the specially composed court of assizes in Paris,

In a few seconds, the hubbub left place in absolute silence. Heavy, stuffy even. The courtroom is full, as it had not been for several months, the civil parties huddle against each other. Seven months after the opening of the trial for the attacks of November 13, the specially composed assize court is preparing to broadcast, after bitter debates, three new sound extracts from the attack on the Bataclan as well as around thirty crime scene snapshots. Factual elements which come, if not to supplement, at least to illustrate the testimonies on this massacre which left 90 dead (40 other people died that night on the terraces of the 10th and 11th arrondissements and at the Stade de France) .

In a few moments, the room is transported to the Bataclan. The Eagles of Death Metal are in the process of interpreting one of their flagship title, “Kiss The Devil”, when dry and cold noises interrupt them. Those of Kalashnikovs. The bursts are linked, then shots piecemeal. After a few seconds of astonishment, cries of terror rise. We perceive the confusion, the movements of the crowd. The howls of pain too. On the benches of the civil parties, everyone or almost is motionless, we sometimes see a hand caressing the back of his neighbor as a sign of comfort, a handkerchief stretched out on the front bench. In the box of the accused, one of them, Farid Kharkhach, stops his ears, the others listen headlong.

“Do we have the hostages?” »

If the second extract is difficult to hear, the third retraces the assault of the BRI, the research and intervention brigade, to free the eleven hostages held by two terrorists. It’s 12:18 a.m., the attack started nearly two and a half hours ago. “Come on guys, come on come on! The tension is perceptible, the shots of heavy weapons resound in the middle of the frightened cries. “We are the hostages! “says one of them. “We run, we run”, “straight on, hurry up”, enjoin the police. Moments later, a loud thump sounded. One of the terrorists – Foued Mohamed Aggad – has just blown himself up. “Do we have the hostages?” asks a policeman. “Yes, they came down. »

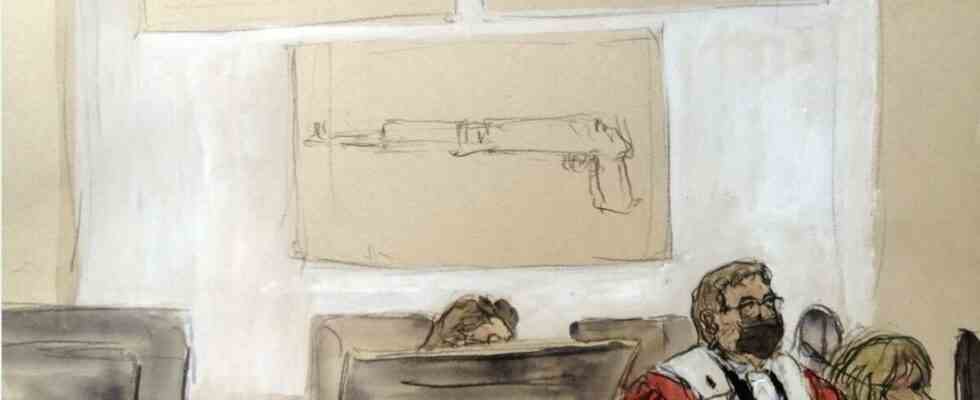

As soon as the excerpts are finished, the light in the courtroom dims. Some civil parties leave the room, about thirty shots are about to be projected. As soon as you enter the Bataclan, you can see a body stretched out on the asphalt. Like a first glimpse of the horror within. As the photos scroll by, the court discovers the mass grave. The tangled corpses near the bar, the grave strewn with blood, the personal effects abandoned in a hurry and all these bodies lying face down on the ground. The victims are often in clusters, near the bar at the entrance to the room, probably the first to be killed, near an emergency exit as they tried to flee, or in front of the scene. The courtroom is seized, almost in apnea. The same description returns, photo after photo, in the mouth of the president: “We see many bodies on the ground…” In the box, several defendants, including Salah Abdeslam, look, others look away.

Show to show?

Listening to this soundtrack, showing the impact of the bullets and the blood, did it promote the “manifestation of the truth”, according to the established expression? “We could not save ourselves from this broadcast, estimated during the suspension of the hearing Arthur Dénouveaux, the president of the association Life for Paris, at the origin of this request. It would have seemed completely absurd to me that the court could withdraw to deliberate without seeing these images. The question has divided a lot within the civil parties. Some had not returned to the trial since the end of October and the sequence devoted to the hearings of the civil parties. Others, on the contrary, who follow the debates assiduously, preferred this time to abstain, not to plunge back into the horror of that night.

Are the images more powerful than the approximately 200 testimonies on the Bataclan attack? Even without photos, all the accounts allowed to imagine the violence of the attacks, the descriptions of the blood which floods the pit, the groans of pain and the last sighs made it possible to visualize them. But the testimonies, even if they overlap, remain a subjective account. Is it enough to realize the reality of a crime? “I want people to know what happened inside, it’s not just a symbol,” says Marie, who was in the pit that night and saw her friend die in her arms. And to insist: “These images and these tapes are hyperviolent but it is the reality of what we have experienced. »