World Heritage

According to a new study, Stonehenge was an amazingly complex solar calendar – and that’s how it worked

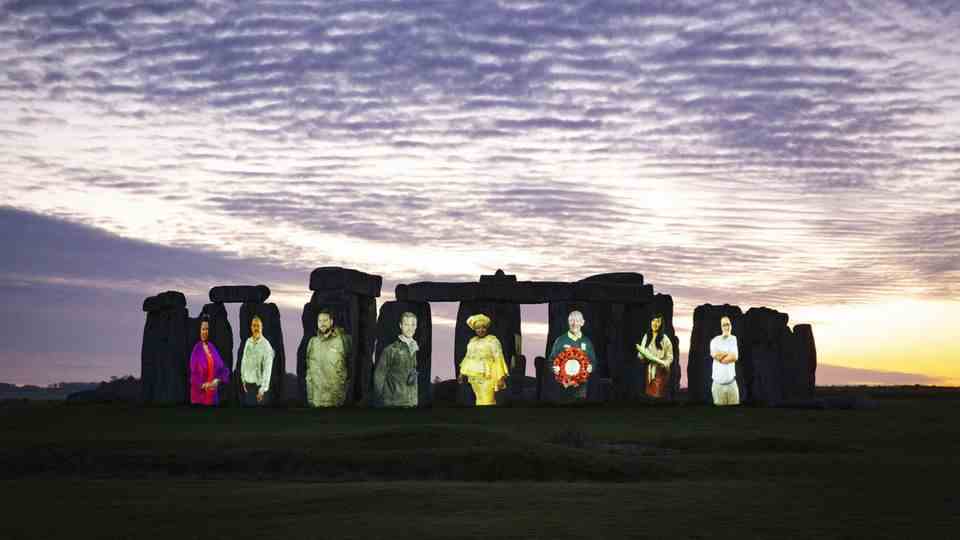

The Rocks of Stonehenge: Scientists have new insights into the spectacular monument

© Blend Images/Chris Clor/Picture Alliance

What was the purpose of the world-famous Stonehenge stone circle for its builders? To this day, science is still arguing about this question. A new study now comes to an astonishing conclusion.

The world-famous Stone Age monument, Stonehenge, near Salisbury in south-west England, may have had a complex solar calendar – far more advanced than previously thought, according to new research.

According to a Tuesday in the study published in the archaeological journal “Antiquity”. The builders may have been able to use the stone circle to depict a complete tropical solar year of 365.25 days, including all months, weeks and days – almost as long as the 365.2425 days used in modern solar calendars. Stonehenge may even have had appropriate stone markers for leap days, according to archaeologist Timothy Darvill of the University of Bournemouth in the UK.

Some researchers have long suspected that Stonehenge had some kind of calendar function, but so far none of the theories have been able to adequately explain how it works. Recent advances in understanding the ancient site have now led to the new findings, writes Darvill.

According to Davill, sarsen in Stonehenge represent the days

The main circle of Stonehenge was built around 4500 years ago. It is now made up of 17 large stones known as sarsen – a term derived from the medieval English word saracen, which once referred to Arabs but then came to mean anything pagan. However, empty indentations in the ground show that the circle originally contained 30 sarsen; the others were eventually taken away, probably for the construction of other buildings or roads.

According to Davill, the Stonehenge year supposedly began on the winter solstice—December 21 or 22, according to the modern calendar—when the days begin to start getting longer again in the northern hemisphere. Throughout the year, each of the 30 sarsen represented a day of the solar month. Each month was also divided into three weeks of ten days each. Their beginning was marked by specially marked stones.

According to the study, a solar year corresponded to twelve passages through this stone circle – i.e. 360 days. There was also a kind of leap month for the missing 5.25 days: “This balancing month of five days is marked by the five trilith stones in the center of Stonehenge,” explained Darvill. The Stonehenge builders even thought of the quarter day at the end of the year and the leap day that is due every four years: four stone blocks lying outside the sarsen circle form a square and could have served as a memory aid for this four-year rhythm, Darvill suspects.

Photo gallery of the Macedonian phalanx – 8 photos

8 images

According to the scientist, Stonehenge may have been influenced by ancient sun-worshipping religions in the eastern Mediterranean, such as the cult of the Egyptian god Ra. The locals may have developed such a calendar themselves, the archaeologist believes, but similar counts for the days and months of a year were also used in ancient Egypt a few hundred years before Stonehenge was built.

“Such a solar calendar was developed in the eastern Mediterranean around 3000 BC and adopted as a calendar by the Egyptians around 2700 BC,” writes Darvill. And the people of Britain at the time, he thinks, may have known about it. There are indications that there were already long-distance contacts at the time of Stonehenge. This was indicated by both isotope analyzes of skeletal finds and DNA comparisons.

“Particularly relevant here is the life story of the Amesbury Archer, buried five kilometers south-east of Stonehenge around 2300 BC in a simple grave, accompanied by an exceptional array of grave goods, including some from continental Europe,” the study reads. “Isotopic analysis shows he was born and raised in the Alps and moved to the UK as a youngster.”

“There are no 12 at Stonehenge”

But there are also doubts about Davill’s new theory: “It’s an interesting hypothesis, but – like any attempt to prove that Stonehenge was a calendar – that’s all it can ever be”, quotes the US broadcaster NBC the British archaeologist Matt Leivers, who has been studying Stonehenge for decades. “There is no way to prove one way or the other.”

In addition, the numbers 30, 5 and 4 are embodied in Stonehenge, but not 12, i.e. the number of months. “There are no 12 at Stonehenge,” said Leivers. “That seems like a pretty big obstacle to me.” Darvill also states this in his study. However, he suspects that the twelve months may have been represented by stones that have since been removed.

Ed Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and author of several books on ancient astronomy, also considers Darvill’s interpretation to be “completely speculative”. Ancient monuments often attempted to combine “cosmic principles” with astronomical alignments, he tells NBC. But there is no point in building a massive calendar out of immovable bricks when much smaller calendars would work just as well.

“Nobody needs to go to the trouble of building a huge monument to keep track of time,” he says. “This is not a good investment of resources”.

Swell: Cambridge University Press, NBC, “Scinexx”