There is a story that explains to the guests at the vernissage in the Pullach community center better than any art historical treatise what makes this Alexander Chekmenev so special. The Ukrainian photographer was roaming the streets with his camera when he came across a homeless man he wanted to photograph. Chekmenev asked if he could please put his cup aside for a moment. The homeless man wanted to know why. Chekmenev: Because it is important for posterity. The next day, the photographer went out again to photograph a second homeless person in the same spot. “The beggar from the day before told the colleague that he should have his picture taken and do everything that was asked because it was important for posterity.”

Iris Trübswetter brought this anecdote to the opening of Chekmenev’s exhibition entitled “Human Dignity – Citizens of Kiev”. The curator for contemporary art and chairwoman of the German Eastern Society arranged the show for the Pullach community center and developed a concept for it together with its director Hannah Stegmayer. One deliberately refrained from showing photos from the current war, said Trübswetter. They wanted to present Chekmenev as an artist, as a documentarian of post-Soviet Ukraine.

With his photos, the Ukrainian wants to bring the events in his country to memory. For almost 30 years he has been documenting people’s lives, precisely where the abysses are deepest, precisely when the pain is greatest. A socially critical artist who looks closely without succumbing to voyeurism, who holds his camera respectfully and with great sensitivity to misery and hopelessness. But Chekmenev also works out the dignity of the individual in his photos.

In his most recent series, the photographer took on those compatriots who were defying the Russian war of aggression in Kiev

Until March 31, the Pullach community center is showing works from various series by the photographer, who was born in Luhansk in 1969: “Passport” (1995), “Donbass” (1994-2011), “Deleted” (2018-2020) and “Citizens of Kiev ” (2022). In his most recent series, the photographer took on those compatriots who were defying the Russian war of aggression in Kiev: a medic, a soldier, a homeless person, a middle-aged couple. Heroes of the bourgeoisie, in the manner of Dutch paintings of Rembrandt’s day, Chekmenev displays their pride against a black background.

The Center Pompidou in Paris has just acquired one of these portraits, but an enlarged print of the photograph hangs in Pullach. It’s a picture of a young woman. The streets of Kiev and the war have left marks on her beautiful face. She looks tired, she is wearing two coats one on top of the other, and if you come close to the picture you will probably not miss the dark lines under her fingernails or the horror in her eyes. Who knows what became of her.

And of course in Pullach, too, the topic of the war that Russia has been waging against Ukraine for more than a year came up. It is more important than ever to show Ukrainian art, said Iris Trübswetter. The exhibition is a political statement. “Precisely because a monstrous war aim is to erase the country’s culture and identity.” In any case, Chekmenev’s photographs have the potential to survive. You have to have a heart of stone not to be deeply touched by the honest directness of his pictures, their sincere aesthetics when walking through the foyer of the community center.

It was coincidence that made the photographer an artist of international relevance and a keeper of history with his “Passport” series. After a good 90 percent of Ukrainians voted for the country’s independence in a referendum in 1991, new passports were consequently needed. Three years later, Chekmenev was sent home by the “Social Center” in Luhansk to those who had not been able to cope on their own: the poor and the old, the sick and the infirm. He was supposed to take passport photos, but the photographer, shocked by the conditions, secretly took pictures of the miserable housing.

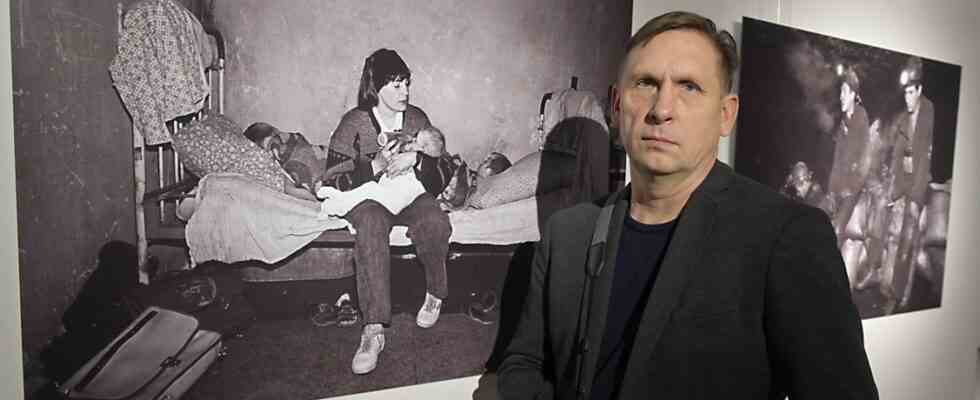

This photo is part of the “Donbass” series, the coal and industrial region on the border between Russia and Ukraine, which is bitterly contested these days.

(Photo: Claus Schunk)

The black-and-white photographs in the “Donbass” series of the hard-coal and industrial region on the border between Russia and Ukraine, which is bitterly contested these days, date from the years 1994 to 2011. In the style of a milieu study, the photographer captured the desolation the miners and their families slipped when many mines closed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. A man is playing the accordion in front of a table with a vodka bottle, a mother is feeding her baby on a bed, behind her the older siblings are sleeping in worn blankets. A man sits awkwardly in a bathtub, his face lathered, and somehow he doesn’t seem to know how to get the foam off. At least that’s how it appears to the viewer in Pullach. This is how it affects posterity.