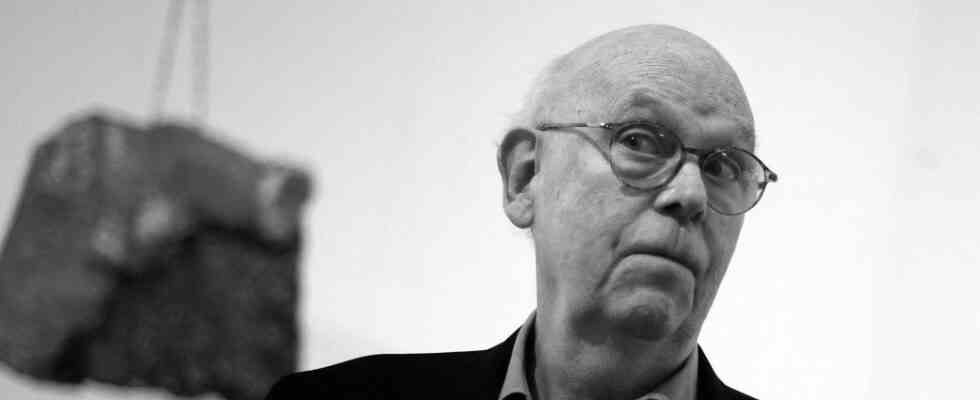

Pop artist Claes Oldenburg is dead. The Swedish-born artist, whose monumental sculptures made him a father of pop art, died in Manhattan on Monday. He was 93 years old. His death was confirmed by the Pace Gallery and Paula Cooper Gallery in New York.

One of his first public sculptures was commissioned by Yale University. The idea of asking Claes Oldenburg for a monument to the “Second American Revolution” went back to a group of architecture students: demonstrations against the Vietnam War were taking place all over the country at the time, and at the same time the protests were directed against a rigid bourgeois society. Oldenburg was supposed to give the resistance a symbolic form. He satisfied the wish in 1969 with a gigantic, phallically raised lipstick, planted on the tracks of a tank. “Make Love not War” – the slogan of the hour seemed to take on a congenial shape.

Oldenburg had already criticized America’s war in Vietnam with a performance in New York in 1967. In this case, rather sarcastically. He called a performance “peaceful civic monument” in which a hired gravedigger dug a pit behind the renowned Metropolitan Museum in Central Park, only to immediately fill it in again. Not only did the excavation allude to the shape of the grave; Oldenburg also understood it as the negative empty space of the base on which the monument otherwise stands. This, too, together with its representative pathos formulas, was thus negated.

What initially arose from the spirit of criticism later made Claes Thure Oldenburg one of the most popular sculptors of the last century. Hardly anyone embodied the success story of art in public space like he did. And only a few artists had steered Marcel Duchamp’s work and the ready-made into their own paths as easily as the artist, who was born in Stockholm in 1929, not only because of his “Mouse Museum” shown at documenta 5 in 1972, in which Oldenburg collected toy pistols of all kinds and let it speak for itself.

By producing everyday service in steel, he made art

Oldenburg selected clothes pegs, safety pins, toothbrushes and bricklayer’s trowels, plugs, stamps and bicycle wheels from the pool of everyday objects, which he inflated to gigantic dimensions and brought into public space. However, by producing these things in steel, he also went back behind Duchamp – and produced art.

Oldenburg once cited humor as the motivation for the large-scale sculptures that he had created since the late 1970s together with his wife, the critic Coosje van Bruggen (1942-2009). Humor helps “to see the world in a new way”, it even has the “function of a ‘higher’ reason”. In Germany, it was the oversized billiard balls in Münster’s Aasee Park that brought Oldenburg’s monumentalization of everyday things closer to the public. Actually, he had wanted to scatter the colossal balls – his contribution to the first, now legendary “Sculpture Projects” in Münster – over the entire city. But in the end there were only three of them, “adapted to the circumstances and the financial resources,” as the naturalized American succinctly stated: The cement balls are still resting in the constellation on Lake Aasee that resulted from a game of billiards in a local bar .

The son of the Swedish Consul General in Chicago, he started out as a police reporter in the crime city. Nothing about this job foreshadowed a later career as one of Pop Art’s most celebrated artists. Fortunately for the art, in the early 1950s, the Chicago municipal news agency decided to retire the reporter from the field and into the copywriting department. As a result, the young Oldenburg lost interest in being a chronicler and finally turned to art. Even as a child he had demonstrated his talent for drawing and watercolours; now he struggled through as an illustrator for an advertising agency before he got serious about his artistic career and went to New York in 1956.

Oldenburg roamed the streets, sought the pulse of the city, created collages out of rubbish. It was inevitably the happening artists who cast a spell on the painter, who was also a poet at the time, in the late 1950s, including the protagonists Jim Dine and Allan Kaprow. “The Street” was what Oldenburg called an environment in the Judson Gallery in 1960: Oldenburg recreated a street scene in a trashy set made of cardboard and jute and on this occasion wrote down what he understood by pop culture at the time – “popular culture”: all that Noise and dirt that the city produces, asphalt, concrete, tar, metal and the “primitives of today”, namely children, the poor, the wacky, the failed.

Oldenburg imitated the tumultuous life on the streets with emphatic happenings like “Snapshots in the City” in narrow cellar dungeons, but then also began to take a closer interest in the consumer world and turned to the economic cycle of the small shops and boutiques on the Lower East Side to. He made clothes, coffee cups, cakes and other consumer goods out of plaster and painted the chunky economic values in an expressionist style that the New York School had produced. If you wanted to, you could still recognize Pollock, de Kooning and Co. in them, but that had nothing to do with the holy seriousness of Abstract Expressionism.

He created his artistically best works for interiors

Oldenburg may have owed his great success to his works in public space – he experienced his artistic best in the mid-1960s, when he was still creating works for interiors. At that time, the young sculptor enriched contemporary sculpture with a decisive variant. He created several versions of one and the same subject, a “hard version” made of cardboard, for example, a “soft version” made of vinyl and a “ghost version” made of faded fabric – and thus immortalized the identical object in different states of mind.

When Andy Warhol became famous with his disaster series and the subject “Death in America”, Oldenburg went to Los Angeles for a few years and immersed himself in the psychological inner life of the affluent society and its everyday things. Crumpled latex and a fleshy toilet bowl stimulate latent libidinal associations in a “Soft Toilet” from 1966, a corresponding “Soft Toilet – Ghost Version” made of whitewashed linen looks ghostly, and the “Toilet – Hard Model” comes across as hard and concrete, sharp-edged and naked. A black “ventilator” or a soft “mixer” with sexual connotations are just as removed from everyday life and characterized by approaches to the monstrous as a “vacuum cleaner” (1964/71) made of aluminum, rubber and cable.

Oldenburg’s flexible concept of sculpture opens the object to the approaches of conceptual art and at the same time holds on to the expressiveness of the material. Oldenburg thus influenced numerous successors such as Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. All in all, his oeuvre testifies to the complexity of the Pop Art phenomenon. The giant bag of French fries, a monumental cigarette butt in the ashtray or a slapped ice cream cone lying there like a whale: it is as if these things were freed from their functions and concepts.

This also applies to his giant outdoor sculptures. They were considered up to date as long as the drop sculpture, the sculpture “dropped” somewhere outside, was not yet called into question by the site-specific, critical intervention.