For more than half a century he helped shape classical music life. The Dutch conductor Bernard Haitink, born in Amsterdam in 1929 and raised there, was one of the most important, precise and powerful orchestral directors of the 20th century. He acted as such – after a short career as a Tuttigeiger – in Amsterdam, London, Glyndebourne, Dresden and Chicago. The Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, however, remained his center, where he began in 1956 as a 27-year-old jump-in and stayed for almost 30 years. The legendary hall of the Concertgebouw has shaped his sense of sound from an early age, the Concertgebouw sound became his character trait, which he also sought as a guest conductor with other orchestras. It was this infinite serenity and calm with which he encountered not only the great symphonies of Anton Bruckner and Johannes Brahms, but also those of Gustav Mahler. Even with this he was looking for more beauty in sound than expressionist disunity. Hardly any conductor achieved such a captivating clarity as Haitink achieved with the Staatskapelle Dresden.

Haitink doesn’t think in terms of the result, but revives the development process, initially approaches it very naively, as if there were reason to hope, the catchy string melodies and horn sounds did not lead to such cruelty as Mahler enforced again and again in his idyllic persiflage . But: The resurrection and redemption scene, in which Mahler continues to write, as it were, Klopstock, can also be heard in Haitink as a cynical grotesque. Even though it doesn’t expose any distorted sounds and grumpy harmonies. He deliberately lags behind others. He said that such music has to be carried over into the present, but he did not believe in completely free interpretation.

One often forgets that there was also an almost revolutionary glow in Bernard Haitink

He is therefore gladly accepted into the hall of honor of the “Werkreuen”, but that is not his style. His performances are far from celebrating masses. Even Bruckner’s Eighth sounds triumphantly desecrated, secular, human with Haitink. Big sheet metal, certainly, but agile and flexible, and it soon becomes clear how subtly Haitink dramatizes music, how calmly it measures the large-scale soundscape. In his last concerts, however, it sometimes seemed as if he was giving the orchestra a completely free hand. Nevertheless: Haitink’s Bruckner story was not even then a stooped, dragging walk to the place of execution, but a ray of light, a large cloud window out and up into free spheres. This is a completely different attitude from the one that is echoed in many Bruckner performances, which often wither into bombastic masses.

One often forgets that there was also an almost revolutionary glow in Haitink. This came to light, for example, in disputes over the financing of culture. London will be remembered. After serving as Principal Conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra from 1957 to 1961 and the Concertgebouworkest, he was appointed Principal Conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1967; From 1987 to 1998 he directed the Royal Opera House. This was closed for renovation in the late 1990s. The amateurish planning and politicized control got out of hand, the choir and orchestra should be dismissed. After a performance of Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” in the Royal Albert Hall, the otherwise silent Haitink stepped up to the ramp and persuaded 6,000 listeners to write to the Ministry of Culture to stop the orchestra from being wound up. Which finally succeeded.

Something similar happened at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, where he resigned in 1988 after internal power struggles with the artistic director. In 1999 he was brought back as an “honorary conductor”. The Staatskapelle Dresden was also affected by Haitink’s furor. In 2002 he took over the orchestra as chief conductor for a transition period of four years. After only two he threw it down. The orchestra had chosen Fabio Luisi, of whom Haitink thought nothing and who had no reputation in professional circles, as the new head. In October 2010, in the run-up to the performance of Richard Wagner’s “Tristan” in Zurich, a scandal broke out when Haitink quarreled with the Isolde singer Waltraud Meier, who was famous for this role – and replaced her.

Conducting, Haitink’s teacher Ferdinand Leitner once said, that is sorting the air

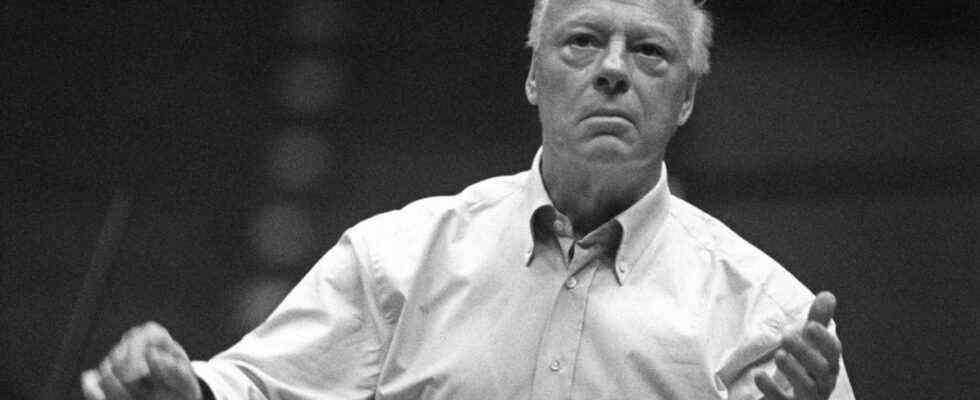

Even at the age of well over 80, Haitink retained an almost pretentious fitness, sheer youthful agility. There was no sprightly stage fumbling like with old Solti, no self-indulgent show conducting like with Maazel, but a kind of spiritualized virility, a mental strength and musically tension-laden flexibility. Except for his snow-white hair and a slight tremor in his left hand, nothing indicated Haitink’s age. His repertoire also remained broad. His recordings include not only, surprisingly for many, remarkable opera recordings, such as Mozart’s “Magic Flute” with Edita Gruberova, but also all of the symphonies by: Ludwig van Beethoven (three cycles, with the London Philharmonic, Concertgebouw and London Symphony Orchestra), Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms (three cycles: Concertgebouw, Boston Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra), Peter Tschaikowsky, Anton Bruckner (many several times), Gustav Mahler (several times except for the eighth) and Dimitri Shostakowitsch, for whom Haitink campaigned. There are also opera recordings, including Wagner’s complete “Ring des Nibelungen”.

Haitink, whose father was held hostage for several months in a German concentration camp after an attack on the power station he ran, could have easily been imagined as an anti-Wagnerian. But, as much as he excited people for music, he was just as enthusiastic about the works of the great masters. That seemed to keep him young too. In 2006 the Chicago Symphony Orchestra named the 78-year-old Principal Conductor. In 2008 he received his second Grammy Award for Shostakovich’s Fourth with this orchestra. In the same year he worked with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe on a Beethoven cycle based on the new critical complete edition, and two years later a cycle with the orchestral works by Brahms.

If anyone knows what music is about, then a conductor like Haitink should know. The reality was different. He was never able to completely shed the deep insecurity of his early years. What does a conductor actually do? He asked himself more often than others – and happily took refuge in the definition of his teacher Ferdinand Leitner. Conducting, he once said, was sorting air. Haitink loved this harmless cynicism. He was not a cynic himself, but rather self-doubting. He also liked to stay to himself in his new domicile south of Lucerne, a posh musicians’ quarter in a beautiful landscape. But on the concert podium, as soon as he raised the baton, all doubts were blown away. He seemed to be acting out of the composer’s head, out of the work. Bernard Haitink, the highly decorated maestro of a bygone era, died last Thursday in London at the age of 92.