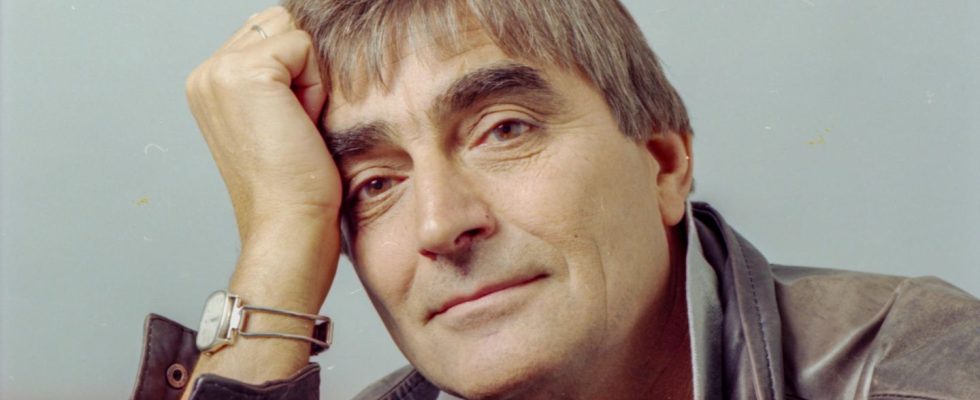

The photographer Mihály Moldvay, who is at star Everyone called him “Mischa”, documented world events for us for decades – and had a big heart for the weak. Now Moldyay has died. An obituary. And his best pictures.

The scene took place at the end of one of the many discussions that took place at the star used to be fiercely fought, sometime in the 80s. It is not known what exactly it was about. But colleagues do remember that star-Photographer Mihály Moldvay clearly expressed that he had a different opinion than the editor-in-chief at the time.

Mischa, as everyone called him, got up to leave the boss’s office, but before he left he said: “If we were in Serbia, I would put a pistol on the table right now.”

Mihály Moldvay came from the Serbian province of Vojvodina, home of the Hungarian minority in what was then Yugoslavia. Throughout his life he remained a child of the Balkans – impulsive, sentimental, sometimes melancholic, combative and definitely hot-blooded. Of course, there was no exchange of fire at the time: Moldvay had no weapon – and the editor-in-chief had no idea of firing him either. Because Mihály Moldvay had long been one of the great photographers of the star. Also because he never denied his origins, but was authentic. “I’m a gypsy, I can say gypsy,” he often said. “I grew up with gypsies. They were all my friends.”

With a cigar, surrounded by microphones: the then Foreign Minister Walter Scheel in 1969

© Mihaly Moldvay

Moldvay had completed an apprenticeship as a car mechanic when he came to Germany in 1962 with the first generation of guest workers. He wanted to study mechanical engineering in Hamburg and shared a tiny apartment with six other newcomers from Turkey. When he saw an advertisement in the subway for training to become a photographer, he spontaneously applied, having never done one before Having the camera in my hand. When he owned his first camera, he heeded the advice of his Turkish roommates that he should send pictures of himself home. He got himself a suit and imitation crocodile leather shoes and posed in front of the Hotel Atlantic with one foot on the bumper of an Opel Kapitan. Then he had his photo taken.

A heart for Eastern Europe

Years later, when he no longer just sent pictures home, but drove there himself with his wife Inge, he was a made man. “If you have money,” his friends there asked, half seriously, half jokingly, “why are you driving a car that doesn’t even have a roof?”

The decade of German terror: In 1975, an RAF commando occupied the German embassy in Stockholm. Two of the twelve hostages are shot, the others are able to escape after an explosive explosion

© Mihaly Moldvay

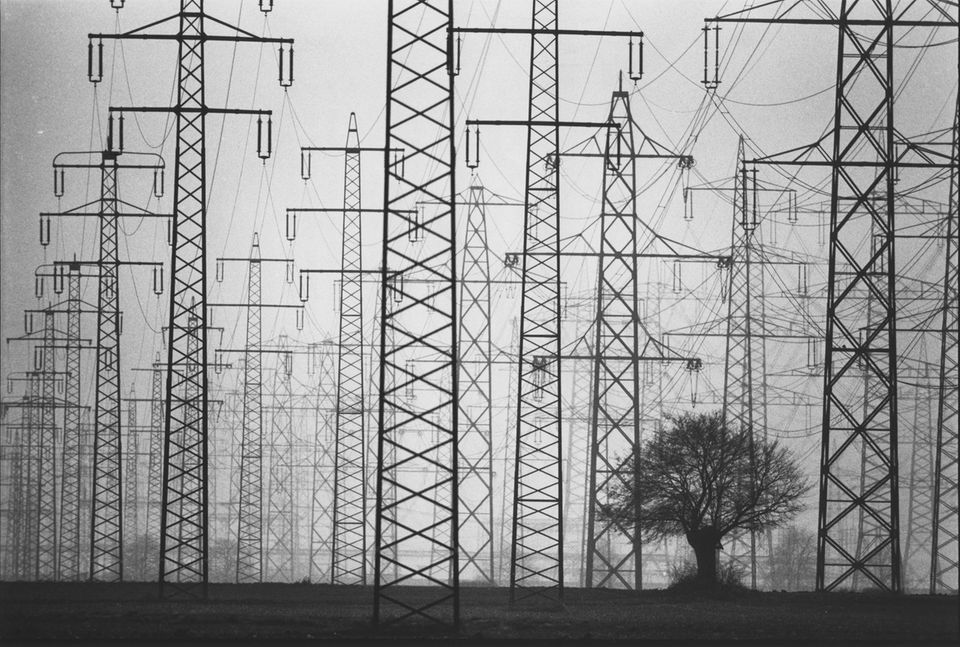

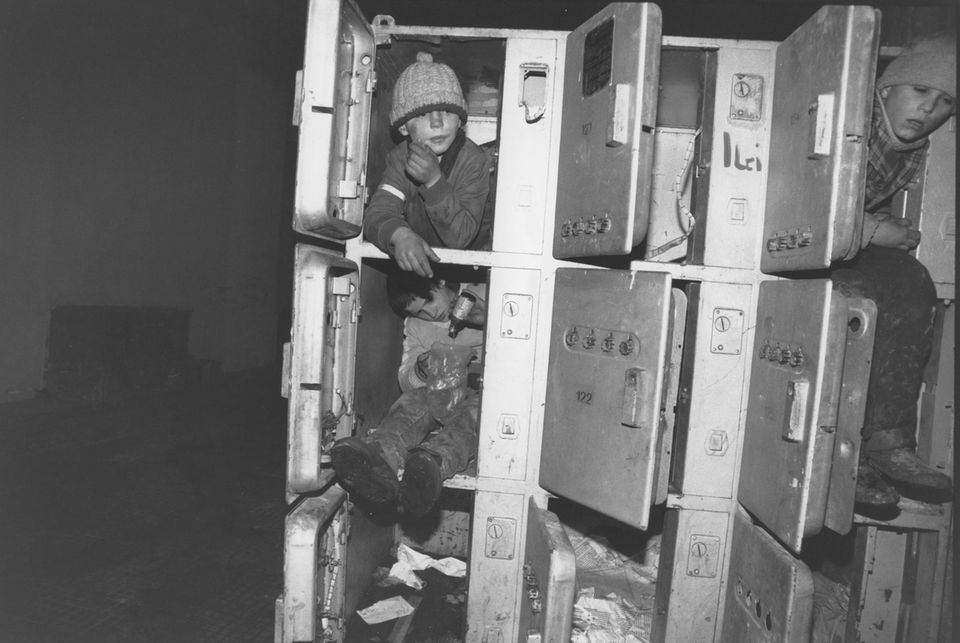

In fact, in the 1970s – after starting out as a photographer for the “Hamburger Abendblatt” – he had long been one of the big names in the scene and for the star traveling around the globe. His apartment was full of photos that he brought from everywhere. They showed fishermen in Greenland, pop concerts in Russia, children in Ghana, drug-addicted minors at the train station in Bucharest. He was particularly proud of a picture with electricity pylons and an isolated tree. The star had never printed it. “But in 1984 it was chosen as the World Press photo in the nature category,” Mischa proudly told visitors – and watched the reaction to the anecdote with narrowed eyes.

A tree, countless electricity pylons: with this photo, which illustrates the contrast between nature and technology, Moldvay won the World Press Award in the nature category in 1984

© Mihaly Moldvay

His specialty, however, was the Balkans and the former Eastern Bloc: with his Yugoslavian passport he was able to enter all of these countries without any problems, even before the fall of the Wall. And he stuck with it because that was where he simply felt most comfortable. He spoke a number of the languages commonly used there, at least for domestic use. He was well connected. And above all: he had a heart for the people in the East, among whom he had found many friends. Once, one remembers star-Author, he and Moldvay got stuck in Romanian Wallachia at night when their car broke down. They knocked on the door of a farm. The woman who came out beamed and threw her arms around the photographer’s neck: “Mischa, my friend, what are you doing here?”

A piece of contemporary history that extends into today: The newly elected Prime Minister of Lower Saxony, Ernst Albrecht, presents his family and pets in 1976. In the middle, to the left of her father, is his daughter Ursula – who today heads the EU Commission as Ursula von der Leyen

© Mihaly Moldvay

Together with the author Kai Hermann, he often reported on the Balkan Wars. A close friendship developed between the two. “He had a heart for victims. The fates affected him. He could also cry,” says Hermann. “And you could rely on him 100 percent.” Hermann describes his colleague “as cautiously fearless.” Mischa Moldvay was not someone who “took incalculable risks.” He didn’t value luxury; the main thing for him was to be close to it. “He was more than just a photographer. He was a co-author. He put his heart and soul into the stories and took part,” says Hermann. Sometimes Mischa was so moved that he forgot to press the shutter button. He didn’t like everyone. But whoever he once let into his heart was lucky. His heart, some say, was as big as the sea.

Children living in lockers – from a Stern report about homeless people in Bucharest in 1991

© Mihaly Moldvay

Kai Hermann, known for his book about Christiane F. and the children from Bahnhof Zoo, raves about Moldvay’s talent for researching, networking and gaining the trust of influential interlocutors. With his contacts he managed to have a photo exhibition shown in the Hungarian National Museum in 2000 – the first at this location. All starPhotographers were able to show their most important images there.

starAuthor Heiko Gebhardt, who also previously reported as a correspondent from the Hungarian capital Budapest, remembers how Moldvay came alive when he was in the land of his ancestors. He was a legend in Hungary. “There he got a dancing step,” says Gebhardt. Whenever Mischa Moldvay came to his hotel, the band had to play the “Song of Sad Sunday” every time. “That made him happy,” says Gebhardt. And: “He suffered from Hamburg” – even though the city had once had a magical attraction for him because he had heard the name over and over again on the neighbors’ radio as a little boy.

“I have to be between people”

Moldvay stayed in Hamburg for the rest of his life – also because he… star a life as a vagabond there. For 35 years he traveled with his camera on behalf of the magazine. Later, long since retired, he said: “I miss traveling, being outside, always among people. I have to be among people, I have to communicate. I would prefer to be in Syria or Egypt right now.”

That was the summit: demonstrators near Bad Doberan on the occasion of the G-8 meeting in Heiligendamm

© Mihaly Moldvay

But he communicated through the pictures he had collected over the years. They hang or hung in numerous Hamburg cafés, in exhibitions that sometimes took place in an empty, four-story house, decorated with suitcases from emigrants. Moldvay then hung a poster on the facade: “This house is occupied.”

Above all, Mihály Moldvay communicated with people who most people just pass by with a sniff. Among other things, he devotedly looked after the homeless people who had set up home in Wehbers Park on Hamburg’s Emilienstrasse. He visited her once a week on his bike. He had specially mounted a device on the luggage rack for his large soup pot, in which he brought his home-made Serbian bean soup to the park residents, regardless of the weather.

Her fate was close to him: Mihály Moldvay supplies Serbian bean soup to homeless people in Hamburg, in the background star-Author Kai Hermann

© Private

Bean soup – that was the unifying element for him. Bean soup was served at every party he hosted in his life. She was only missing from the opening that a young cartoonist organized for him almost a year before his death from cancer, as if that were a sign. Mihály Moldvay had to be pushed to say a few words. Then he spoke heartwarmingly. “I have dem star a lot to be grateful for. I got through that star “I’ve seen a lot and learned a lot,” he said. “But it wasn’t always my world either. A lot of things were too smooth, too elegant, too expensive for me.”

was 83 years old. He leaves behind a daughter and two sons.

Anyone like Mihály Moldvay who would like to support homeless people in Hamburg:

“Homeless Aid Midnight Bus”

Diakonie Foundation With Humanity Hamburg

IBAN: DE76 2005 0550 1230 1432 55