Max Beckmann and his wife Quappi, Mathilde Kaulbach, pose for the camera on the beach. Run in and out of the water. Do winter sports. Traveling with a lot of luggage that others carry for you, nice hotels. The private photographs and film recordings of the Beckmanns between the wars speak of light-heartedness and joy in mundane life. So not necessarily what one generally associates with Max Beckmann – whose late expressive art is better known for black-outlined heaviness, a struggle with existential needs and a melancholy grounded narration of old myths. Which should also be part of their success story in the USA: just so German, enigmatic, dark, rooting in metaphysical depths. The painter, who died in 1950, played a part in this story. He oriented himself to the writer Gottfried Benn and the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and once called his own paintings “the shed skins of myself”.

Max and Quappi Beckmann on vacation in Zandvoort around 1934. Bavarian State Painting Collections, Max Beckmann Archive, Max Beckmann estates

(Photo: Bavarian State Painting Collections, Max Beckmann Archive, Max Beckmann Estates/Bavarian State Painting Collections, Max Beckmann Archive, Max Beckmann Estates)

The autumn exhibition at the Pinakothek der Moderne expressly does not follow this somber path, instead focusing not only on Beckmann’s works of art but also on his quite cheerful biographical traces, on postcards, photo albums, diaries, vacation films or the vaccination certificate for the dog Butchy. The exhibition architecture presents the small-format documents from the extensive Munich-based Beckmann archive in fixtures that open towards the hall like ship cabins with a view.

The show, which is dedicated to travel, comes across as surprisingly light-footed, considering that Max Beckmann’s travels were not all as pleasurable as the beach excursions of the early 1930s. In 1937, the National Socialists confiscated hundreds of his works from German museums and showed his works in the Munich disgraceful exhibition “Degenerate Art”. Beckmann immediately emigrated to Amsterdam with his wife and several paintings. He had already lost his professorship at the Frankfurt Städelschule in 1933.

How deep this cut must have been can be best understood in contrast to Beckmann’s carefree life during the Weimar Republic. The painter, accustomed to success, was well connected, his works sold and were prominently displayed in numerous museums. His second marriage to Quappi from the upper-middle-class Munich Kaulbach family also secured him.

Max Beckmann: “Young Men by the Sea”, 1905

(Photo: © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, museums, inventory no.: G 543/© Klassik Stiftung Weimar, museums, inventory no.: G 543)

While he used to cultivate a late impressionist style with bright colors and soft forms (as in the large canvas “Young Men by the Sea” from 1905), his works gradually became more angular, clearer, and more colorful; finally he outlined most of the figures in black, which sharply demarcates them from each other and from the world. The modern disconnection and loneliness entered his art even more obviously. At the same time, however, he never abandoned figurative and narrative thinking, but instead struggled to translate the old heroic stories and myths, especially from antiquity, into the present. This made his art accessible to all those who were still alien to the new era.

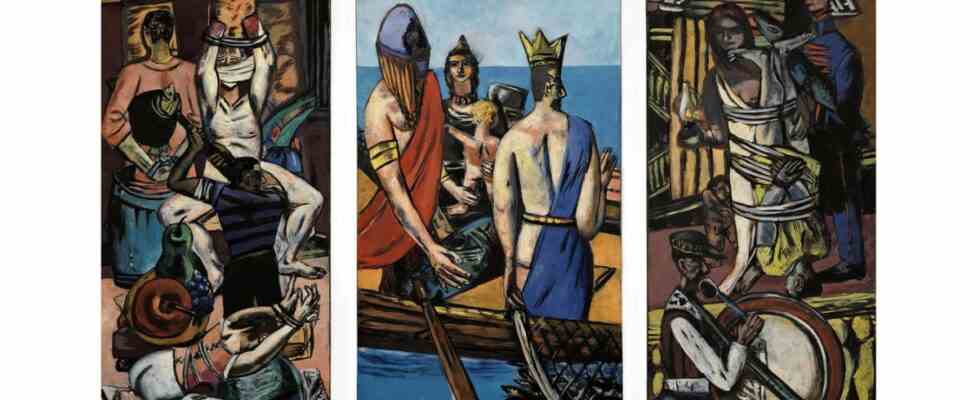

An example of this is the triptych “Departure”, created between 1932 and 1935, which has belonged to the New York MoMA since 1942 and made the German famous in America. The show in Munich opens with the three paintings and shows them slightly offset, which means that the two outer paintings come particularly close to the visitors. In earthy colors they show oppression, torture, bondage. Bound people are mauled, a plate of fruit remains out of reach, a drummer dullly beats the rhythm of hopelessness.

In the middle, however, a small group in a fishing boat on a bright blue sea sets out for new horizons, including a fighter, a king, his wife and their child. The painter later declared the blond child in the center of the picture to be the embodiment of freedom and wrote: “Freedom is what matters, it is the departure, the new beginning.”

In Amsterdam he writes a diary, paints, drinks a little and keeps himself alive

For Max Beckmann, however, freedom does not only remain a vague hope in this picture. Something that feeds on old ideals without having arrived in the here and now. Neither in terms of content nor form did his enthusiasm for experimentation go as far as that of Pablo Picasso, with whom he liked to be compared and who is also placed on the same level in the exhibition catalogue.

The two are linked by their joyful break with the conventions of modernity that have only just emerged; Picasso, however, reinvented himself and painting as a whole from scratch, flies into the open, celebrates his artistic freedom – Beckmann, on the other hand, sometimes prefers to drive his black body with the handbrake on. The driver himself is too much the focus of this art, with his possibilities and limits. Which is why Beckmann’s self-portraits, which show an ego torn between anger, doubt and despondency, are particularly impressive.

Max Beckmann: “View from the ship’s hatch”, 1934.

(Photo: private collection/private collection)

So the Munich show is only showing one figure from art history, a modern painter among many? No, she locates Max Beckmann for the first time in his – involuntary – life theme, leaving. This is a story of loss that could hardly be more topical: someone who was sure of his earned status is thrown into the void and can only dream of the sea in his two-room apartment in Amsterdam, soon also under German occupation. He writes in a diary, paints, drinks a little and that’s how he keeps himself alive. At some point he sells pictures again and finally, after liberation, can start a new life in the USA.

Did the king and the blond child help him? Rather the knowledge of abysses, which in the 20th century by no means remained a metaphysical matter, but became reality. And into which this artist looked.

Max Beckmann: Departure. Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich. Until March 12th.