There are stories that are too good to be true, but this is it: Terry Waite negotiated the release of Western hostages in the 1980s as plenipotentiary for the Archbishop of Canterbury in Lebanon. But in January 1987 the parliamentarian himself was arrested by Islamic Jihad and spent almost five years in captivity, most of the time chained to a wall, in solitary confinement. Communication wasn’t easy: Waite couldn’t speak Arabic, his guards didn’t speak English, but at least he was able to tell them that he needed something to read. The thought of someone wanting to read was alien to them, as Waite later said, they were fighters, but so good-willed that, without realizing the irony, they first brought him a book about breakout adventures and then a breastfeeding advisor. In the end he drew a penguin and made it clear to his guards that he wanted a real book, a book from the publisher that had the bird in the sign.

It has become a transcultural trademark that the global German publisher Random House, which renamed itself to Penguin Random House after taking over Penguin Books last year, cannot do without. In order to cover up the Gütersloh Bertelsmann background a bit and to remind of the tradition that it has bought, the publisher has just released tried-and-tested titles by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tania Blixen, Stefan Zweig and Jane Austen as “Penguin Edition” and advertises them with “Zeitlos”. Iconic. Colorful “.

That timelessness is probably right: twelve years ago, the Penguin envelope was included in a stamp series with “British design classics” alongside the Mini, the Concorde and the red telephone booth. The design comes from Edward Young, who began his career at The Bodley Head. Allen Lane was one of the directors. After a visit to Agatha Christie, he had looked for travel entertainment for the return trip to London at Exeter station and found nothing, so he founded Penguin Books, a publisher with books for the “intelligent layman”.

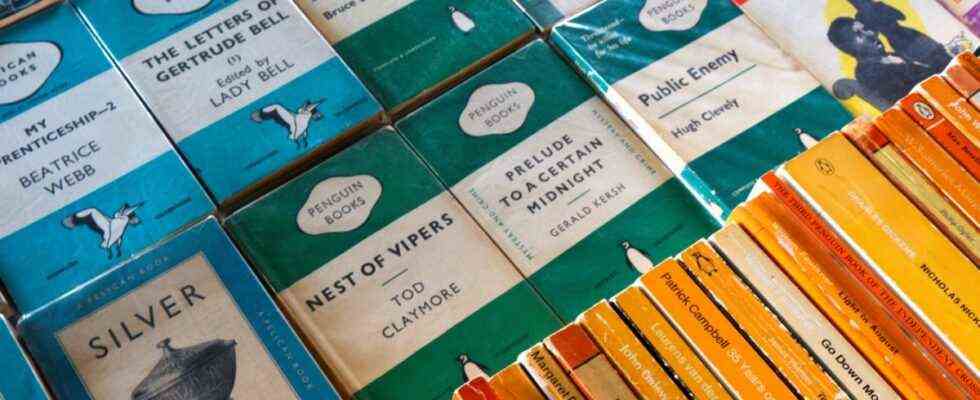

Advertisement for the new book series in old covers, new in German.

(Photo: Pressefoto / Penguin Edition)

In the publishing industry in the thirties, not only in Great Britain, there was enormous conceit, combined with a scarcely less fear of the present. In 1932 Kurt Tucholsky sent his “Avis to my publisher” Ernst Rowohlt with the request repeated three times: “Make our books cheaper!” At Chatto & Windus, the price reductions, which were also a consequence of the economic crisis, were responsible for the fact that “our industry has so hard to come back from the slump”. There was general despondency: in his capacity as a publisher of Faber & Faber, the poet TS Eliot preferred not to publish James Joyce’s “Ulysses” for fear of censorship; Allen Lane brought out the book at Bodley Head.

With his new publisher, Lane wanted to get into the present and reach a large audience. Against the cultural arrogance, he consciously relied on cheap goods. The book was an industrial mass product and technically infinitely reproducible. His books were supposed to cost no more than sixpence or the equivalent of a pack of cigarettes, selling modern times. A penguin incubator was installed in London’s Charing Cross Road, from which a book could be pulled out 24/7.

The idea of making money with a small price and a large circulation despite a modest trading margin came from Germany, more precisely from Hamburg, where Christian Wegner had founded the Albatross publishing house three years earlier together with Kurt Enoch and the naturalized Englishman John Holroyd-Reece, which should provide continental Europe with books by English authors in the original language. The books were produced according to the golden ratio, they came out in paperback and only had the typography on the cover as an illustration.

Allen Lane, founder of Penguin Books, presents an unabridged edition of DH Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” after a court ruling acquitted the book of profanity.

(Photo: Central Press / Getty Images)

Lane leaned on this model, the albatross became another, not quite as airworthy bird. The publisher’s own myth has it that Lane sent his assistant Edward Young to London Zoo for inspiration to do animal studies. Afterward, Young complained about “how bad these birds smell”. Nevertheless, the penguin became the heraldic animal of the Book Age.

As a fearless marketer, Lane found nothing in posing with a real penguin holding a book in front of his nose. If the animal had learned to read, it could even have enjoyed it, it was “The Thin Man” by Dashiell Hammett. The first titles included Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” (translated as “In Another Land”), a Percy Shelley biography by André Maurois, and Agatha Christie’s “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” (“The missing link in the Chain “), the first Hercule Poirot.

But it was not least the design that determined the consciousness here. Lane organized his books by color: orange for novels, blue for biographies, and green for crime novels. The competition had predicted that he would fail quickly, but he was lucky because he got into business with another cheap home.

According to Woolworth legend, it was the wife of Clifford Prescott, who is responsible for buying gifts and haberdashery at Woolworth, who noticed a volume of Agatha Christie that Allen Lane had laid out on the table with other books. Lane offered a Woolworth-compliant low price, he promised to ship in bulk, and the publisher was in business. Bodley Head, which continued to rely on high-priced prestige works, had to file for bankruptcy soon after Lane’s departure.

Churchill lost the election, and the Conservatives blamed the Penguin books

It was the thirties, the world was in unhealthy movement. Europe began to recover from the economic crisis, but Spain drifted into civil war, in France there was a popular front, in Germany the Prussian Junkers pushed their Hindenburg and Hitler into the Reich Chancellery. As a result, the first pogrom against the Jews was organized, and the exodus to France and England began. Penguin delivered the educational program for a troubled time.

Socialist George Bernard Shaw praised Lane for affordable books. He also got him his first original edition by updating his “Guide for the Intelligent Woman to Socialism and Capitalism” and leaving the two-volume work extended by the chapters “Sovietism and Fascism” to Lane, which could thus open the Pelican series of popular non-fiction books. Although Lane as a publisher would hardly have suffered from a major public education assignment, but simply wanted to earn money, the cultural and political influence of Penguin should not be underestimated.

When Winston Churchill lost the parliamentary elections in July 1945, just two and a half months after Germany’s unconditional surrender, which was owed to him, the Conservatives blamed the defeat on the influence of the Penguin books. England became temporarily socialist. Exactly one year later, to celebrate Shaw’s 90th birthday, the “Shaw Million” was published – ten of his titles were reprinted in an edition of 100,000 each. Customers were queuing in front of the station bookstores, and the publisher was having trouble reprinting.

Contrast between high circulation and low readiness to read the purchased book

The intelligent layman was generously cared for in the decades that followed. The paperback spread, the book market grew every year, accompanied by the ritual clapping of hands-over-the-head because of the mass production. After the Second World War, Rowohlt actually followed Tucholsky’s request and began his rotary novels. The other publishers soon developed their own low-cost series. In 1959, the young Hans Magnus Enzensberger examined the phenomenon of “education as a consumer good” and complained about the fact that the paperback publishers did not enjoy the “luxury of a ‘line’, any kind of view of the world and literature”, not without culturally critical undertones wanted to do more and therefore at best differed “like the car models of two brands in the same season”. As a shrewd dialectician, in the contrast between high circulation and low readiness to read the book once bought, he found the peaceful conclusion: “The good thing about the paperback is that the large number of its consumers, who shy away from the risk, are the minority of its readers subsidized. ” Three years later, Enzensberger was the publisher of Edition Suhrkamp, a series that actually became unmistakable, not least because the designer Willy Fleckhaus gave it its memorable, simple image.

Edward Young, on whom the penguin image goes back, left the publishing house in 1939, enlisted in the war the following year and became the first volunteer who was allowed to command a submarine. After his military service he returned to the publishing industry. In 1952 he published his autobiography under the modest title “One of Our Submarines”. Two years later it was published as a paperback by Penguin, volume number 1000 for the bird and war hero wreathed in laurel. The book became, how could it be otherwise, a Penguin bestseller.