The wife of Franz Stepan’s client summarized the matter devastatingly: men who look for rusted car parts and are as happy as children with every find. Should we make a film about this? Stepan smiles and reaches for one of the massive illustrated books lying on a glass table in front of him. Yes, you should, especially he should, when he got the job in November 2010. The result was a film whose premiere had people even crying at the end. How does it work? Crying over a car story?

Cars and nerds are probably some of the most difficult categories when it comes to excitement and identification. And even though Stepan has already made and produced a lot of films in his life and is familiar with dramaturgical storytelling thanks to his background as a filmmaker, a project on this topic is initially about as sexy as a documentary about bent paper clips. Although such a regulatory faux pas would never happen to Stepan, in the thickest illustrated book in front of him in the terraced corner house in Ottobrunn, 20 notes in five colors are accurately pasted. Because if there’s one thing you need for this project, which at the end resulted in a film that’s brilliantly told and produced with a highly professional feel, that makes car drivers melt away and gives car ignoramuses at least a spark of understanding for their fellow human beings with a passion for horsepower, then that’s patience, Endurance and treasure hunter genes.

Anyone who lets 74-year-old Stepan tell even three sentences about this crazy story is falling into the trap that leads tens of thousands of television viewers to watch old Nazi documentaries every night. This ability to captivate others is not just due to Stepan’s pleasantly dark voice, which you would even believe if she said: Driving is environmentally friendly and the mobility of the future. Like so much about the man with white hair, his voice is film-worthy. But the tension comes from the plot, which took place almost 100 years ago.

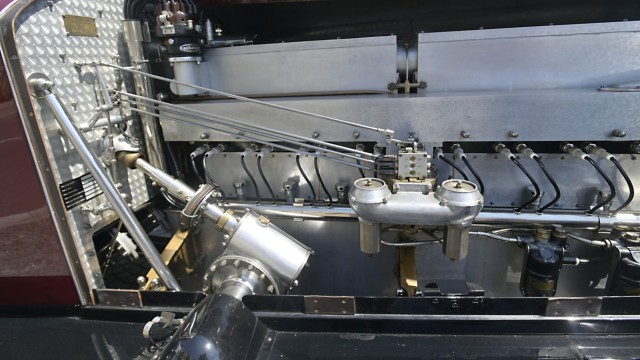

First, there are the rusted car parts of a famous car with a very famous name. The Bugatti Royale Prototype Type 41 from the Italian manufacturer Ettore Bugatti of the same name from 1926. The man and his family alone are worth several documentary seasons. Bugatti, now on this sunny morning in autumn 2023 Stepan is leafing through his bookmarked volume, which he bought for 600 euros at the beginning of his research. It’s a documentarian turning pages: in silence, the movements perfectly formed, the way you would want someone turning pages if you had to record them. Stepan grabs a page at the top right edge of the book with his thumb and forefinger, lifts it slightly and lets his fingers slide down to the end of the page. A crackling and wiping sound can be heard. And Stepan’s sentence: “It was considered the greatest, most expensive and most beautiful car”, perhaps not of all time, but undoubtedly at the end of the 1920s.

The Bugatti cost three times as much as the most expensive Rolls-Royce of its time and six were built.

(Photo: Claus Schunk)

This Bugatti cost three times as much as the most expensive Rolls-Royce of its time, and six were ultimately built. And they were worth it, as the engine alone, “half an aircraft engine,” was still used in French trains until the 1970s. Consumption: a royal 40 liters per 100 kilometers.

Money is always important in a good deal, and one of these cars from back then was recently auctioned off for around 18 million euros, reports Stepan. The film is about the first Bugatti prototype, which the builder himself drove into a tree at the end. Stepan says: “But that’s not true.” Good documentary filmmakers are usually good researchers, and good researchers are happy when they find out more than others before them. Stepan found out that Bugatti didn’t hit a tree, but another car. Through a newspaper article that appeared at the same time. Nothing happened, but the car was over and then disappeared from the scene. And that’s exactly where Stepan’s story begins.

The engine alone, “half an aircraft engine,” was used in French trains until the 1970s.

(Photo: Claus Schunk)

Which would also bring the treasure hunt category into play: When Stepan was contacted by his client in 2010, whom he only calls his client, the following happened. In the USA, a car expert found the chassis of the car that crashed at the time. If you will, the immortal remnant of perhaps the greatest car of all time.

It was the flagship car of a manufacturer that won almost every race in the world with its cars in the 1920s. Bugatti wanted to build a royal car, the prototype was almost six meters long, weighed more than three tons and, from the rather immodest Ettore Bugatti’s point of view, was only suitable for kings, which is why he called it Royale. This vehicle, externally more like a horseless carriage, traveled 200 kilometers per hour.

Stepan took notes for the conversation with the SZ journalist. His handwriting can easily compete with wedding card writers, who always seem as if the person who creates the highest capital letters would be hired as a treasure map calligrapher for the next blockbuster.

There is an almost mystical story about each of the seven royal chariots; three are now in various museums

After the frame appeared in the USA, the thought arose in the world of car enthusiasts: could it be this legendary car? By then it was known that Bugatti had produced a total of seven of the vehicles, with different bodies that were placed on the chassis like oversized hats.

One of them was made by the Munich coachbuilder Weinberger. As befits a Munich version, the Weinberger model was purchased by a celebrity doctor. He shipped the car to the USA, where it also broke down. And so there is an almost mystical story about each of the seven royal chariots, three of which are now in various museums. But of course the most beautiful story has to be told by number one, the one about the Bugatti accident. Stepan’s client was made aware of the find and decided to attempt to restore this work of art on wheels.

A major conflict in the industry should be mentioned at this point: the difference between an original and a faithful replica. How many original parts are enough to declare an item original?

Stepan’s client put together a team of specialists who were authorized and provided with the necessary resources, including from the Bugatti company, to resurrect the car. So the men – surprisingly only men – followed every lead and flew “sometimes around the world for a screw,” as Stepan puts it. “It was like Oceans Eleven, the best specialists in Europe.”

Like any good storyteller, the man on his sofa always sprinkles in a little anecdote, be it that Ettore Bugatti, who was not prone to reserve or modesty, had the same number plate screwed onto all his cars in order to save taxes. Or that he refused to buy one of his cars from a king who was willing to buy because he didn’t like the man’s table manners.

Stepan followed the automobile men’s treasure hunt for years, and whenever there was a find or a small milestone was reached in the reconstruction, he flew out with his camera team and filmed. Also the employees of the fashion company Hermes, who faithfully recreated the trunk case. And in the middle of it all is the meticulously researching and seated man who is now looking into the past from his sofa. He goes through his notes again and wants to at least mention two things again. He shot and produced a “few thousand films” and was twice awarded the prize for the world’s best film at the New York Documentary Film Festival. After saying “weltbester” he pauses, immediately talks about the importance of teamwork in film and actually doesn’t want to have it pronounced “weltbester” anymore. You could say that a documentary filmmaker pays attention to completeness, but there is also a tiny bit of sympathetic vanity.

The two documentaries about Bugatti are now on their own for the first time platform free to receive. At the premiere a few years ago in Molsheim in Alsace, where Bugatti is based, and the second premiere in Germany, “some people had tears in their eyes.” But why? Because of another screw found or because of the impressive pictures of the blacksmith from Paris who forged the leaf springs?

“You’re excited to see whether they can do it,” says Stepan. “But people were also gripped by the emotions of the people who worked on this project.” And whose dream has come true. To restore a car that, in the end, is also a work of art “and a part of contemporary history.” Stepan’s films are now being shown at a motor vehicle school as a motivational aid. “And that’s what I hope for: that this passion is an example, also for other professions and situations in life, because you see: This is how you can give meaning to your work and what you do.” As an exception, a text about a documentary filmmaker can end with a last sentence that is just a little too thick, as befits a film ending.