It is fascinating to follow thirty articles which, according to the conception of the editor Magnus Brechtken, are intended to depict the status quo of the academic analysis of National Socialism (NS). The deputy director of the Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ) Munich-Berlin deliberately wants to present a compendium, not an encyclopedia. That is much.

The processing is understood as a cumulative process that is by no means linear. Four phases can be identified in it, which are in focus: the analysis of NS up to 1945, the research into the causes and the difficult beginning of coming to terms with the end of the war, empirical research and how it has been dealt with since 1945 and, as a core problem, the historical continuity and discontinuity from Weimar to in the early 1970s.

The post-war period was dominated by a “communicative silence” (Hermann Lübbe) of guilt feelings in the knowledge of the Nazi crimes. Enlightenment research on NS, initially subsumed under the term totalitarianism, had no place there. The template was too firmly established by an unscrupulous power elite and an allegedly seduced people. In the 1960s, individual case studies emerged that at least shed new light on institutional dynamics.

It is good to remember that standard works such as Raul Hilberg’s “Destruction of the European Jews”, Christopher Browning’s “Quite Ordinary Men” or Saul Friedländer’s study on the persecution of Jews in Germany were only published in the late 1980s.

The “Volksgemeinschaft” only came into focus very late

How difficult it was to face the genocide was basically shown by the historians’ dispute, in which Ernst Nolte declared the mass extermination as a reaction to Stalinist persecution that had already been practiced. Only after a phase of specific perpetrator research did research move into the focus of research in the 1990s on the “German national community”. Instead of seeing “the people” as a seduced whole, which was not in any collective responsibility, one now turned to the collaboration of the general population, which ultimately legitimized the murder of the Jews as an “end in itself out of ideological certainty of faith” (Magnus Brechtken).

New assessments followed, such as the structure of the Empire, its connection to the Third Reich, and the classification of Weimar. The central position of the compendium remains to analyze structures from a rational position. This is the only way to see the claim for a convincing research cross-section secured.

Renowned experts dedicate themselves to the individual topics with an enormous range with a wealth of relevant details and further comments. To a certain extent, the publisher has preceded the review by its institutional foundation, the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich. Perhaps symptomatic of the slow course of historical introspection is that there has been no history of the institute so far. The IfZ itself also played no role in the discussion about historians in the Third Reich, which was only to change at a conference on the tenth anniversary of Raul Hilberg’s death in 2017. Originally, the institute was an initiative of cultural politicians who were looking for an independent research location without the influence of the Allies. The IfZ started its work in the summer of 1950 with the three branches of archive, research and publications. The first thing to do was to work out a historiography of the concentration camps in which more than 1.7 million prisoners were murdered.

Hannah Arendt and Raul Hilberg did pioneering work

We owe Frank Bajohr an excellent overview of the development of Holocaust research. Above all, he points to the turning points in research, such as the trend towards “everyday history” since the late 1960s, the inclusion of racism in the human sciences and the great importance of Auschwitz and the Nazi extermination policy in the 1980s including the question of the singularity of the Holocaust based on the historians’ dispute in 1986/87. Around this time, an international connection to Holocaust research was established, supported by new research institutions. Christopher Browning presents American perspectives and refers in particular to the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem and Hilberg’s original edition of “Annihilation of the European Jews” from 1961.

Both became legendary through Hannah Arendt’s characterization of Eichmann as the “banality of evil” and Hilberg’s view of the Nazi regime as a “machine of annihilation” in the form of party, military, ministerial bureaucracy and industry. In addition, he presents the positions of the scientific controversies in the finest of facets. The Hamburg historian Ulrike Jureit vehemently criticizes a culture of remembrance “which normatively says goodbye to questioning its own interpretations and practices over and over again, which at best wants to understand the confrontation with the Holocaust as a conservative ‘preservation of the past'”.

Magnus Brechtken (ed.): Working up the National Socialism. A compendium. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2021. 720 pages. 34 euros.

It was thanks to the public prosecutor General Fritz Bauer’s initiative in 1958 that a bundle of 100,000 search files was handed over not to the Federal Archives but to the Central Agency for Investigating Nazi Crimes in Ludwigsburg, where they were processed by lawyers and historians. In the absence of sufficient posts, the so-called preliminary investigations threatened to fall asleep if the United Nations had not sent the wanted list with 30,000 new suspects to Ludwigsburg. Instead of leaving the investigation on the Fuehrer’s order and a general emergency of orders, the investigators revealed a whole bundle of motives for “taking part” from collective peer pressure, competitiveness, willingness to adapt, greed and lust for murder. An example of this was the case against the Hamburg Reserve Police Battalion 101, which was involved in shooting operations by the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied eastern areas.

What was decisive, however, was the associated change in the dogmatics of assisted murder. For the first time, it was sufficient that subordinate members of the guards could be convicted without directly participating in the killing. However, the number of convictions remained unsatisfactory despite the evaluation of new local sources.

The Federal Ministries’ coming to terms with the Nazi past only got off to a slow start; Nowhere was the response more pronounced than in the investigation into the role of the Foreign Office between the Third Reich and the FRG. The anthology only roughly goes into the Nazi past of the GDR ministries, until today a reappraisal is at the beginning.

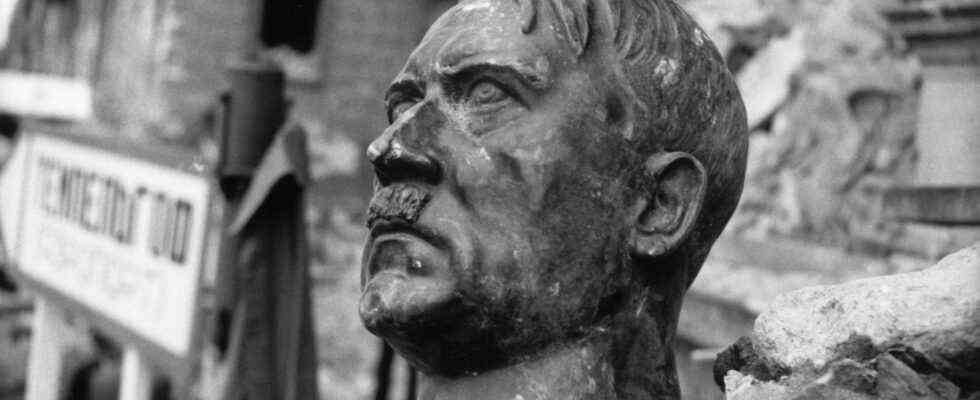

The researchers counted 3700 titles on Adolf Hitler alone

An interesting aspect of looking back at the past is devoted to an article about Hitler’s books from 1945 to the present day and thus also about the role of publishers as actors in politics of the past. Apart from the broad spectrum of around 3700 titles about Hitler and the NS, television alone put the “collective memories of the Nazi genocide on a new basis” with the media event “Holocaust” (1979). In the opinion of Wulf Kansteiner, the film set a “never again achieved standard for self-critical memory politics” with an audience rating of 40 percent, even stronger than “Schindler’s List” (1993).

However, it was only these popular formats that established a certain relationship with the subject. Unlike Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour documentary “Shoa” (1985), which only four percent of households tuned in. Kansteiner suspects that the future of Holocaust memory will be determined by video games and artificial intelligence. How strongly the defense against knowledge about war and the Holocaust was anchored was shown by the flood of homeland films, but also military glorifications of the 1950s. It was not until the turn of the millennium that there was a boom in films about the Nazi era.

In a wide arc, the volume is devoted to the state of research in the looted art and provenance debate in great detail. The dimension of German memories of the past has only recently become apparent when the question of the relationship between the Holocaust and colonialism stand. Certainly, as Bill Niven suggests, there is a causal link, but the two should not be “played off against each other”.

Brechtken’s great compendium does not claim to be complete, nor can it. A broader overview of the state of Nazi research, however, is nowhere to be found.