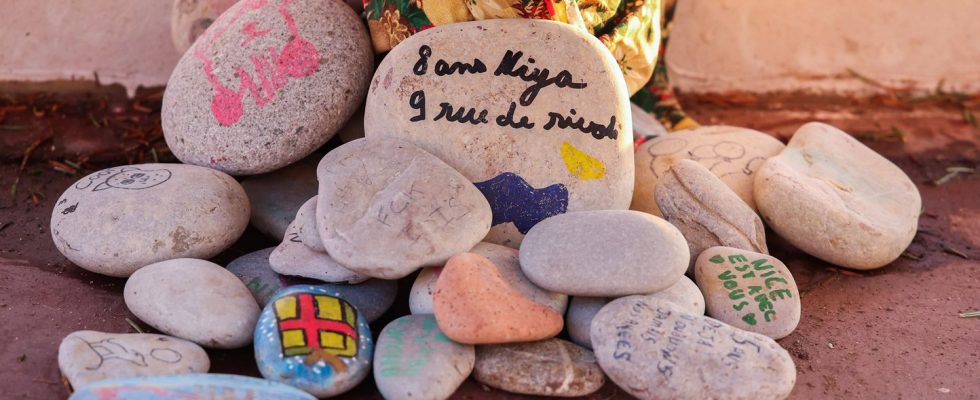

They saw absolute horror. That of an assassin truck zigzagging along the Promenade des Anglais to kill as many people as possible. A machine of death which sank into the middle of a carefree family crowd gathered to watch the July 14 fireworks display. In 2016, 86 people, including 15 children and adolescents, were killed in the Nice attack. There were around 3,000 children at the scene of the attack, according to the lawyer for the association “A Way for Children”, Marie-Pierre Lazard.

Traumatic

For the first time, during the appeal trial which opens this Monday, child survivors of the attack – some were only four years old at the time of the events – will give their memories and traumas on the stand. An ordeal that can be cathartic or overwhelming. Other children, on the contrary, refuse to talk about what they experienced, “out of modesty” or “because they are rebuilding themselves and do not want to rekindle the trauma,” explains the lawyer who defends nearly ten children victims of the attack.

“In this type of case, there are different issues that collide, that of arriving at the judicial truth and that of protecting children because testifying at the bar makes you relive the traumatic event, this can be harmful as positive,” underlines Aurélien Martini, vice-prosecutor at the Melun court, deputy secretary general of the Union of Magistrates (USM).

Or cathartic

Some minors decided to take the plunge during this appeal trial, reassured by the feedback from those who had testified at first instance. But a criminal court can be impressive and disconcerting. So, to prepare them, the lawyer “receives them, listens to them, guides them by explaining that what interests the court: what they experienced, what they remember, what marked them the most, and consequences that it has in their lives.”

The lawyer also cites the case of this little girl aged 11 and a half to four years in 2016 – “determined to speak”. She was not able to testify in 2022 before the specially composed assize court, the president then pointed out her young age. “He was a magistrate specializing in terrorism matters, not used to hearing from children,” comments Marie-Pierre Lazard. “Those who are not experts are not necessarily very comfortable discussing these extremely serious facts with children,” she analyzes.

From concrete to horror

This experience can nevertheless weigh in on the debates. “It’s always interesting to hear these testimonies, it can fill in empty areas, vague areas,” confirms Aurélien Martini. Even more so when the memories are intact. This word, however, has no more or less weight than that of an adult, “it’s a different level,” adds the magistrate.

For the court, when the message comes from the mouth of a child who is still young, “it has its effect, it becomes more concrete”, argues Marie-Pierre Lazard. It is also additional proof “that children were knowingly touched”, which can affect the sentences. Of the eight defendants sentenced to sentences of two to eighteen years in prison at first instance, two appealed.

The fact remains that the collection of children’s words, although it has evolved a lot in recent years, is not an easy thing to do in court. “There are a multitude of interlocutors and some may use oratorical techniques to obtain the answers they want,” warns the magistrate. It is then the role of the presiding judge to remind us that we are dealing with children. Even when they experienced the worst.