At the Assize Court of Nanterre,

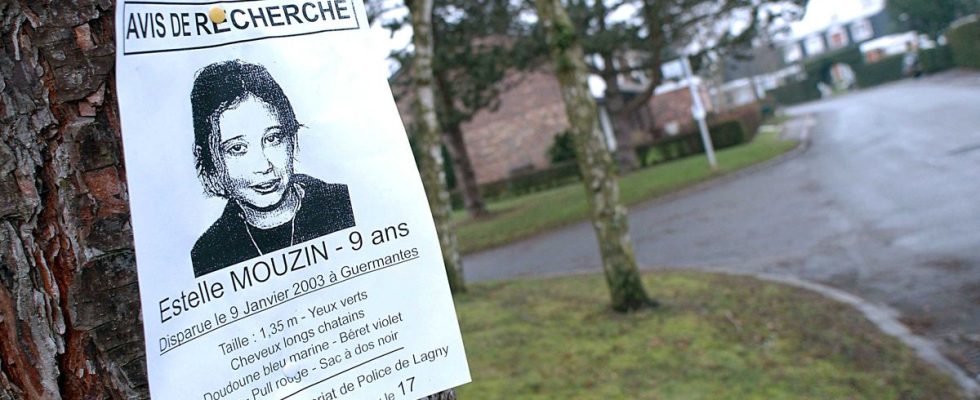

Of Estelle Mouzin, we know above all a photo. That of a little girl with a shy smile on her lips, dressed in a red sweater, a few strands escaping from her bun. This photo, taken at school, his loved ones don’t like it very much. Not only because it is the one which illustrates the search notice issued after his disappearance, in January 2003 in Guermantes, the starting point of their ordeal. No, it’s mainly “because it doesn’t represent her,” assures her sister Lucie. It is true that we do not see in this photo the “clown”, “the chatterbox”, the “extroverted” and “vivacious” little girl described by her relatives before the Nanterre criminal court. So they asked for other photos to be shown. She appears hilarious on a merry-go-round, all smiles at the sea or on a giant buoy with her brother and sister…

From the accused box, Monique Olivier, stooped silhouette, shapeless white sweatshirt, looks at this short family album. As since the trial opened on November 28, his face remains unfathomable. In 2018, after denying any involvement in this affair for fifteen years, she admitted to having served as an alibi for her ex-husband, serial killer Michel Fourniret. A few months later, she admitted to having kept the 9-year-old girl for several hours while she was confined. “You are a mother yourself, many times over. Can you imagine your boys suffering the same fate as Estelle? Kidnapped, raped and left alone in a freezing house, in the dark,” asks Suzanne Goldschmidt, Estelle’s mother, with strangled sobs in her voice. She testifies by videoconference after having hesitated for a long time to do so. “I didn’t want to be plunged back into this abominable nightmare,” confides this well-dressed 67-year-old woman with short hair and piercing blue eyes.

“It’s been 7,636 days since Estelle disappeared”

At the bar, everyone talks about absence, this unfathomable void to be tamed. “Today, it has been 7,636 days since Estelle disappeared,” begins her father Eric, comparing his ordeal to a marathon of which we do not know the distance. Listening to them, one and the other, we realize to what extent staying standing, living – surviving rather – has been a constant struggle. “Little by little, life returned to normal, but not for us. The house remained frozen with his things, his toothbrush, his presence,” writes Lucie, his older sister, in a letter read at the audience. Everything takes them back to that cold day in January 2003. Estelle’s photo plastered everywhere, the media who closely follow this issue, the way others look at them. “It was kind and compassionate, but it always brought me back to horror,” recalls Suzanne Goldschmidt.

Added to the pain is this “overwhelming feeling of guilt”, as Lucie puts it. Estelle’s mother blames herself for letting her daughter come home from school alone, “her key around her neck”. “It is a serious error, a fault that I blame myself for and will always blame myself for.” Arthur, his older brother, blames himself for having decided, when his parents divorced, to live with his father. “Maybe I would have been the one in charge of picking up Estelle. » Everyone talks about this “guilt of existing”. Every time he travels, reads a book, watches a play, tastes a dish, Eric Mouzin has in mind that his daughter is not there to enjoy it. ” It’s still amazing. We become guilty of the acts committed by others, analyzes this man with graying hair and blue Klein glasses. Guilty for living and being there. Guilty for being there and she isn’t. »

“It took me a long time to live my life”

Faced with horror, everyone did what they could. Arthur “armored himself emotionally” by making sure he no longer felt anything. “It took me time to live my life and no longer watch it pass in front of me,” insists the young man, soft voice and long hair pulled into a bun. After staying in the Guermantes house for two years, Suzanne Goldschmidt left for the other side of the world. She cut herself off from the investigation, following developments from afar. Conversely, her ex-husband, Eric Mouzin, strived to keep the case alive, to fight so that it does not fall into the limbo of justice. For twenty years, he lived to the rhythm of meetings with investigators and judges, quotations of the file, summary reports. For twenty years, he strived, with his lawyers, to bring into existence the “Fourniret” lead in which the Versailles PJ, long in charge of investigations, never believed. We had to “keep pedaling so as not to fall,” he sums up.

Monique Olivier listens to them one after the other, her eyes glued to the ground most of the time. No emotion comes through clearly, it is difficult to detect what she is thinking, feeling, even understanding. She does not react when the little girl’s parents reproach her for her actions. “She knew exactly what was going to happen. From the moment a person was kidnapped [par Michel Fourniret], it ended with an assassination,” insists Eric Mouzin. “Monique Olivier could have saved her, she chose not to. It’s abominable,” adds Suzanne Goldschmidt. Monique Olivier admitted to having looked after the little girl while Michel Fourniret worked, which allowed her to form an alibi. To the investigating judge, she indicated that she had not had the “idea” of releasing her.

“I’m monstrous, I know”

Questioned after these testimonies, the accused assures her, it is not because she is not crying that she does not feel anything. “It was said that I didn’t show any feelings, that’s not true. Hearing these people talk, cry, it does something to me. » She asks for forgiveness, even though she knows well that she is “unforgivable.” » Monique Olivier searches for words, hesitates, corrects himself. In the room, the silence is heavy. “I’m monstrous, I know. If I were in their place, I wouldn’t forgive myself. »

The president seeks to take advantage of this moment to make her speak. Starting with this question that haunts the little girl’s loved ones: where is Estelle’s body? The search operations – around ten – did not make it possible to find the child’s whereabouts. “If you have an ounce of humanity, tell us where you put Estelle,” her mother begged. “We took twenty years, and maybe more, since Estelle’s body is still not there,” her father insisted. “If I knew it, I would say it. I would like Estelle to be able to rest in peace, and for her family to be able to reflect. But I do not know. » The magistrate insists. “Burying a 9-year-old little girl, we remember that…” “It’s not that I don’t want to, it’s that I don’t know,” she retorts, annoyed. A brief exchange which sets the tone before his hearing scheduled for Monday morning on the merits of this case.