Most biographies end with death. But then a new biography begins, the afterlife. Here too there are early years, life crises, misjudgments and disappointments, here too the return of what has been suppressed, the slow fading away or the suddenly flaring up of vitality. But all this takes place on the projection screens of posterity.

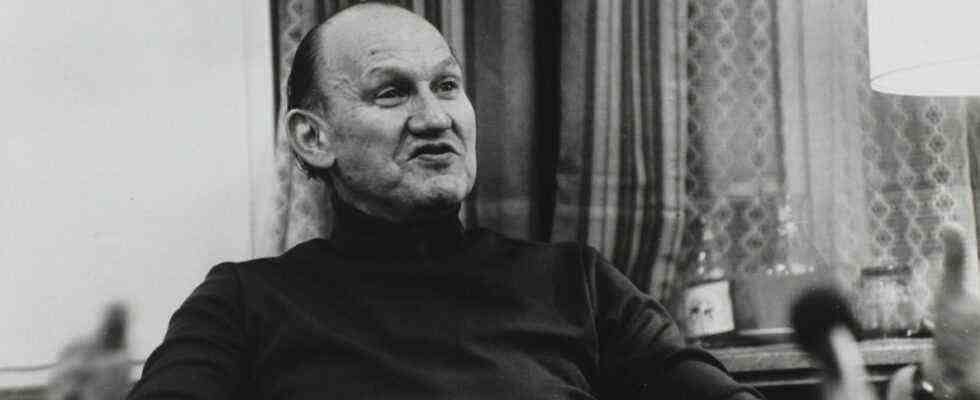

Franz Fühmann was born on January 15, 1922 in Rochlitz in the Giant Mountains Bohemia, son of a pharmacist with entrepreneurial ambitions, was a pupil in a Jesuit seminary near Vienna for four years from 1932, was old enough to become a partisan of Sudeten-German National Socialism at a young age and to volunteer for military service when war broke out in 1939. At first he had to be content with the Reich Labor Service, but in 1941 he went to the Eastern Front as a signalman and later to Greece.

After the end of the war, while he was a prisoner of war in Russia, he was not only introduced to Marxism-Leninism, but was also informed about the crimes of National Socialism. He understood the lessons so well that he quickly rose to become a teaching group leader in Antifa schools and, when he was released to the newly founded GDR in 1949, a little later he joined the apparatus of the block party NDPD (National Democratic Party of Germany) and spent almost a decade as a cultural and political leader functioned.

He did not live to see the end of the GDR, he died in July 1984

He started writing early and was already in the NS-Zeitung The Empire published, published a volume of poetry in Hamburg in 1942, printed in 1955 meaning and form, the journal of the “German Academy of Arts” in the GDR, two poems. From 1958 he lived as a freelancer between East Berlin and Märkisch Buchholz. He was also able to cross the border to West Berlin after 1961, often returning with bags full of books.

Everything he experienced found its way into his writings, all delusions, all self-accounting, all discoveries in the universal library. In 1982, when he was in Munich Sibling Scholl Prize accepted, he confessed to the GDR as his state, with which he had long been at odds, whose Stasi monitored him and torpedoed his readings after he had been one of the first to sign the petition against Wolf Biermann’s expatriation in 1976. He did not live to see the end of the GDR, he died of cancer in July 1984 and is buried in Märkisch Buchholz.

On Tuesday evening, the Minister of State for Culture and Media reported that Claudia Roth, in the plenary hall of Berlin Academy of Arts at Pariser Platz, how she discovered a gap in her bookshelf at the end of last year. A friend who lives in Pankow asked her when she took office: “Claudia, please don’t forget Franz Fühmann’s 100th birthday!” The name meant nothing to her, it wasn’t part of her world. The Minister of State for Culture confessed this ignorance with remarkable frankness to an audience that had come together to celebrate the writer. She spoke of “the missing F” as a gap in her awareness of what German culture is. So she had started reading Fühmann. That was meant programmatically. Wrongly, she continued, many authors who were part of the reading experience in the then “new countries” were “put aside” in the 1990s. The gap in one’s own bookshelf as a symptom of the divergence between German and German reading biographies.

With “Twenty-Two Days or Half of Life” he reinvents himself

The program to change this is welcome, but it doesn’t fill in “the missing F”. Franz Fühmann is more than a writer from the former GDR who moves into the distance with her. If anything can be read from the abundance of events dedicated to him around his 100th birthday in Berlin, it is this: Franz Fühmann has reached a phase in his afterlife in which he is growing more and more into the universal library.

Yes, it’s true. Those who, like Claudia Roth, were born in Ulm in 1955 had fewer chances of meeting Fühmann at a young age than, for example Ingo Schulze, who sat on the podium of the academy during her welcoming address and later reported how Fühmann was read to him as a child and how the volume “The Wooden Horse – The Legend of the Fall of Troy and the Odyssey of Odysseus” was given as a gift. But sat next to him Isabel Fargo Cole, born in Illinois in 1973 and came to Berlin in the early 1990s, became a German writer here, discovered Fühmann through his protégé Wolfgang Hilbig and translated both into American. The moderator of the evening was Elisa Primavera-Lévy, born in Munich in 1976, as editor of the magazine meaning and form responsible for the Fühmann focus in the current issue, including the essays by Isabel Fargo Cole and Ingo Schulze.

Cole sees the word “change” as a keyword for Fühmann, who in the “Jewish car” gives an insight into the inner worlds of his childhood with the blood ritual-soaked horror images of anti-Semitism and the belief of the young National Socialist in the final victory and later the embodied the personal union of anti-fascism and Stalinism that shaped the early GDR. In 1973 he reinvented himself as a writer in the diary of his trip to Hungary “Twenty-Two Days or Half of Life” (1973) and placed the terrifying vision of how easily and sensibly he could have become a guard in Auschwitz at the center of his life story.

If he should now leave the garbage cans of GDR literature, so much the better

A week before his 100th birthday, the Literature Forum in the Brecht House dedicated an entire cycle of events to Franz Fühmann. Here, too, the children’s book author Fühmann appeared again and again, with his new tales of myths, his Doris Zauberbein, the snow lake in which the vowel cascades of the “e” foam up, with the promising title “The steaming necks of the horses in the Tower of Babel”.

But whether Corinna Harfouch read from Fühmann’s work or contemporary authors pondered him, the language game, unrest and terror always formed a triad. For example, when Kerstin Hensel, born in 1961 in Karl-Marx-Stadt, which is now called Chemnitz again, recognized the “false perception”, the “suppression of the catastrophe of the century” in Fühmann’s poem “In Frau Trudes Haus” and his transcription of Grimm’s fairy tale, which she had experienced in her own German family home. Annet Groeschner, Berliner born in 1964, discovered syntactic models of fragmentary writing in Fühmann’s “Two Days”. Julia Schoch, born in Bad Saarow in 1974, adopted Fühmann’s sentence “It’s only when I’m writing that something becomes problematic for me” and remembers how she salvaged Fühmann’s books from a box with discarded GDR literature in the early 1990s.

On the evening of January 15, a long evening of readings for Franz Fühmann took place in the St. Matthäikirche at the Kulturforum, with Volker Braun, Uwe Kolbe, Kerstin Hensel and many others, including Jan Philipp Reemtsma, who testified that Fühmann had been part before 1989 of German literature as a whole. If he should now finally leave the garbage cans of GDR literature, so much the better. In the literature forum in the Brecht House, the literary scholar Roland Berbig gave an insight into his previously unedited pocket calendars, which are written in a private shorthand variant that is difficult to decipher. Like the lecture “About the mythical element in literature”, which Ingo Schulze described as an “eye opener” for his own writing, they show the dialogue with the universal library, the old myths, their interpretations by Thomas Mann and Karl Kerényi, the many years of reading Sigmund Freud, the growth of the dream notes to a large body of work. The gap in the shelf of the Minister of State for Culture has not yet been fully measured.