analysis

As of: 23.09.2021 8:17 a.m.

For decades, market laws, deregulation and free trade were very popular with economic politicians. But the trend has long since turned: a stronger state is needed.

The head of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Gabriel Felbermayr, is considered a liberal economist who is no friend of state control and who has long been campaigning for free trade and open markets. With a view to the economic policy concepts in the Bundestag election campaign, he states: “Practically all parties in Germany see the state as an actor that is becoming more important.” And they would like politics in certain areas to play a more important role in the future.

Felbermayr cites climate protection, industrial policy, dealing with internet giants and the topic of foreign trade as examples. Is the state on the advance and the market on the retreat in the foreseeable future? A look at the election manifestos shows that while deregulation has been the focus for decades, many parties now want to flip the switch more intensely, to strengthen the steering effect of the state.

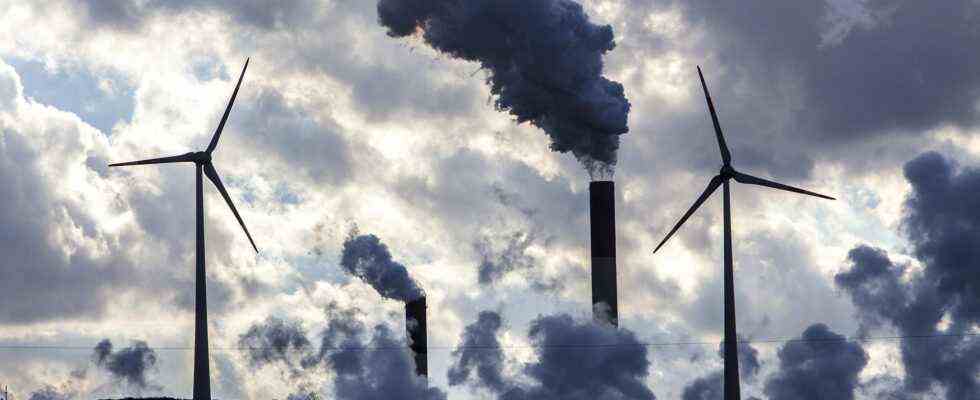

Climate protection

There is a consensus among all Bundestag parties with the exception of the AfD that the state is called upon to do more to protect the climate. However, the proposals differ as to where and how strongly the state should intervene. The difference between the FDP and the Greens is clearest.

The Liberals rely on a central regulatory instrument: the CO2 price. The Europe-wide emissions trading should include all relevant sectors with a CO2 cap that decreases annually. Emissions would become more expensive from year to year, which would drive the changeover. From the FDP’s point of view, this is a market-based model, although the price of CO2 is likely to rise rapidly and noticeably.

The Greens, on the other hand, favor a whole range of measures in addition to gradual CO2 pricing: for example, bringing the coal phase out to 2030, the gradual introduction of a solar roof requirement, a speed limit of 130 on all motorways and the ban on newly registered combustion engines from 2030. Chancellor candidate Annalena Baerbock emphasized in the second triad: “Every ban is also a driver of innovation.”

The Union and, above all, the SPD want to expand renewable energies more quickly – through financial support and accelerated permits, for example for wind turbines or power lines. The left wants to disempower the “energy companies”, get out of coal faster and increase energy efficiency.

A steering instrument that has already been adopted by the current federal government is the Climate Protection Act. It makes sector-specific specifications for the annual CO2 savings, for example in the energy industry, in the building sector, in transport or in industry.

Industrial policy

Linked to the climate protection goals is the renewed interest of many parties in industrial policy. The SPD, Union, the Greens and, to a certain extent, the FDP are convinced that the industry cannot manage to phase out CO2 without the state. CDU Economics Minister Peter Altmaier recently noted with satisfaction that the need for an industrial policy in Germany was not at all controversial in the election campaign. “That catches the eye in a very beneficial way,” said Altmaier.

Union, SPD, Greens and FDP want to promote climate investments in the economy through grants or tax. The current federal government has already launched programs worth billions for large emitters such as the steel, chemical and cement industries.

In particular, the Greens, the Union and the SPD want to temporarily pay for higher production costs due to climate protection. “The state will compensate for the additional costs,” says SPD chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz. The three parties and the FDP also show sympathy for protecting domestic industry from competition from other regions of the world if there is no climate-friendly production there. A conceivable instrument is the so-called border adjustment – a kind of climate tax for the competition.

The industrial policy approaches are also about technology funding. The Greens are strongly focusing on expanding electromobility. The Union, SPD and FDP also have high hopes for the use of hydrogen in transport and industry.

Internet companies

All parties agree: Internet giants should be asked to pay more. Even FDP boss Christian Lindner, who regularly campaigns for the relief of companies, calls for stricter rules for the digital global corporations: “That is a question of international tax law. It needs a global minimum tax.” The Union emphasizes that Google, Amazon and Co. should pay their taxes where they generate sales. The Greens speak of a digital corporate tax. The left demands that dominant monopolies on the European level be smashed.

Free trade

For years there was bitter argument in Germany about the treaties: TTIP, CETA or the free trade agreement with the South American Mercosur states. The global trend towards more protectionism is now taking hold on this issue. TTIP has already been buried by the former US President Trump, the CETA agreement has been waiting for ratification in Germany for years, even if it is in force for the time being, and the contract with the Mercosur states is due, among other things, to environmental concerns in many EU States on the brink.

In Germany, the Greens still do not want to agree to the CETA treaty, while the left sees free trade treaties as a fundamental threat to global justice. The Union and FDP, on the other hand, affirm that they want to ratify CETA and campaign for further agreements. The SPD emphasizes the goal that environmental and social standards should play a greater role in trade agreements. The AfD wants more protection for the national economy and is against deepening EU cooperation.

Big topic, little debate

More market, more state – the head of the Institute for the World Economy Felbermayr considers the question of how things will continue in economic policy to be one of the major topics of the future. However, that hardly played a role in the election campaign – apart from individual discussions about bans or market-based instruments in climate policy: “I can deal with the question of where do we actually want to go, how the relationship between the state and the economy should be shaped not seen.”