The name of the “Ruangrupa” collective, which took over the artistic direction of the Documenta Fifteen this year, is made up of the words for “space” and “form”. That seems program. The classic Museum Fridericianum became the “Fridskul”, whose pillars were painted black and covered with graffiti by Dan Perjovschi. More than thirty other venues are on the plan, and the number of participating artists and activists is estimated at more than 1,500. Here is a course of important stages:

Nest Collective brought European electronic waste back to its place of origin and dumped it in bales in the Karlsaue.

(Photo: Catrin Lorch)

The Nest Collective

From a distance, the dark gray and white cubes look like minimal art, if only because they contrast so strikingly with the lawn in front of the orangery. As you get closer, you can see that the edges appear dented, that nothing has been smooth and designed, but rather computer scrap that has been roughly compressed – and now held in shape by steel bands. For “Return to Sender – Delivery Details” (2022), the East African “The Nest Collective” reversed the direction in which garbage normally travels around the world. Now the scrap lies in the Karlsaue, cleanly reduced to the dimensions in which bales of old clothes travel halfway around the world, only to rot there in heaps. The small pavilion that towers behind the sculptures and in which a video is running is made of precisely such bales: they report what the clothing donations from German containers are doing, how the suppliers are destroying the African textile industry and how the small street vendors and shopkeepers are being scammed those affected themselves.

Documenta running gag: Hamja Ahsan’s advertising signs for fictitious chicken roasts appear in a number of places.

(Photo: Catrin Lorch)

Hamja Ahsan

They hang at the entrance to the Fridericianum, above the counter in the Documenta Hall and on the facade of the Ruruhaus, at the Nordbad and on the cement of the old Bettenhausen factory – the simple, blue, white and red logos of a chicken stand. It’s only after a few stations that you notice that the name and the chicken change, that “Kaliphate Fried Chicken” is advertised and then “Kabul Fried Chicken” again. So Hamja Ahsan successfully creates the impression of a thriving fast food chain. The conceptual artist and satirist is alluding to the fact that chicken stalls in south London in the 1990s were considered suspect because it was said that jihadist networks recruited their offspring there. In the Islamophobic climate of Great Britain, entire districts are still defamed as “Londonistan”. As far as gloomy assumptions are concerned: Hamja Ahsan feeds them with enthusiasm. The (combative) names and promises of the advertisements combine to form a narrative of their own. Especially at night when they shine lonely in quiet Kassel.

Richard Bell

The “Aboriginal Tent Embassy”, the tent used by Australian Aborigines to fight for their sovereignty in Australia for fifty years, now stands directly in front of the Fridericianum. Behind the museum’s pillars, Richard Bell’s paintings occupy two stories in the rotunda. Bell is one of the few Aboriginal artists invited to Documenta Fifteen. His monumental, brightly colored motifs are mostly based on media images, showing blockades, demonstrations, marches – and in addition to the serious and combative figures, the focus is on the slogans, which deal with land grabs, environmental destruction and climate catastrophes. The authentic “Tent Embassy”, a small black tent that he transported from Australia to Kassel, is now to become a meeting point, a place for discussions and readings – for indigenous artists, rappers, filmmakers and slam poets. And all that with, that’s an exception at this exhibition: direct transmission to the Internet.

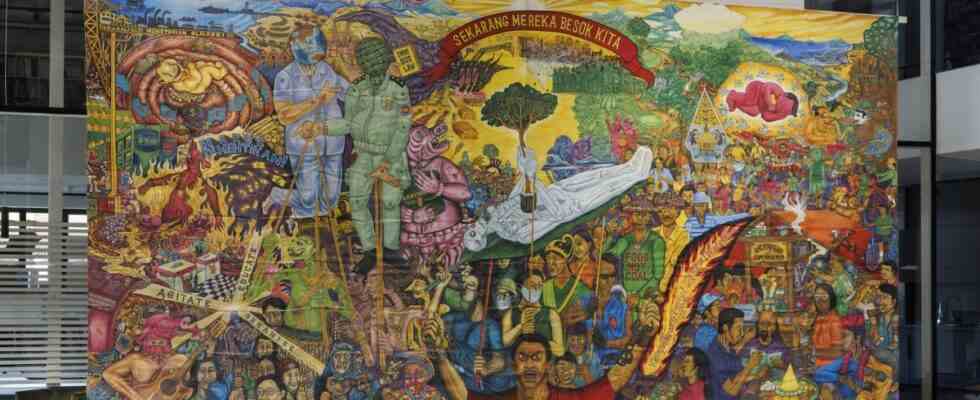

Taring Padi brought Indonesian protest culture to Kassel.

(Photo: Frank Sperling)

Taring Padi

Made from cardboard and bamboo sticks, the figures are conspicuous in a bed in front of the Documenta hall. There must be dozens. In addition, the members of Taring Padi were allowed to set up in the east swimming pool in Bettenhausen. The result is one of the most beautiful exhibition locations of the Documenta Fifteen. The banners, protest posters, flyers and above all the handy figures – once moved from the street to an exhibition – look refreshingly museum-like, almost like paintings. The members of Taring Padi came together at the art academy and founded the collective after the fall of the dictator Suharto in the late 1990s. Since then they have been working on a visual language that is reminiscent of protest posters, cartoons, agitprop and new figuration, but also quotes the Javanese shadow play with its exaggerated figures. Instead of staging exhibitions, the collective prefers to make themselves useful with workshops in which they teach others how to put slogans and figures on a banner, on a piece of paper or even a T-shirt. Taring Padi will unfurl one of their oldest and most beautiful banners under a bridge on the banks of the Fulda – and thus expose it to the weather and possible vandalism.

Cao Minghao & Chen Jianjun

Water is the theme artists Cao Minghao & Chen Jianjun are currently working on. Their long-term study “Water System Refuge #3” not only determined data in headwaters, on wet meadows or Tibetan high plateaus in Sichuan, China, but also in Kassel, which is characterized by industry. In their research, the two ecologists and artists also refer to other information, to clues from the animal kingdom, to myths, religion or the knowledge of shepherds. Her tent, which was made of yak hair, among other things, based on nomadic cultures, stands in front of the orangery and is intended to become a meeting place where research results and discussions can be brought together. The tent itself will be returned to nature after the exhibition to rot. Slippers are to be made from the yak hair, which as a product will directly strengthen the economy of Chinese organic farmers.

Sada (Regroup)

The fact that the film room on the first floor of the Fridskul was hidden behind a curtain is certainly meant as protection. “Sada”, which means “Echo” in German, is a network for filmmakers that Iraqi artist Rijin Sahakian founded in 2010 in an environment marred by wars, attacks, destruction and sanctions. For the Documenta, Sahakian once again called on networkers to submit films under the title “Sada (Regroup)”. The result is a collage of contributions in which more of the living conditions of international artists becomes visible than one can bear.

An escape manifests itself in the images of seemingly aimless car journeys through Turkish cities. The messages that come in continuously via the Internet, SMS, news images and warnings of attacks are also displayed. The stream of consciousness of an artist is reflected in interrupted, dismembered and chopped up, in whose thoughts art becomes an increasingly distant memory. In contrast, the animation of an Arab animator, who reports on being tortured by the Islamic moral police, on escape and a fragile new beginning, has an almost fairytale effect. One contribution begins with photographs of American bombers – and with the resolution of the artist, who has returned to Iraq from the USA, never to want to look at a “picture produced in America” again. Sada is more than an echo from the South — it’s a countershot to the Western news perspective.

Animation of the video group Sada.

(Photo: Nicolas Wefers)

instar

At thirty, Tania Bruguera was one of the stars of the eleventh Documenta, directed by Okwui Enwezor. Her installation – the subject of shootings – was emblematic of globally attentive, politically alert art. Instead of settling in New York, Berlin or London, the Cuban returned to Havana, where she not only worked as a dissident, was spied on and cut off from the internet, but was also repeatedly imprisoned.

She then founded the “Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (INSTAR)” in May 2015 with a collective reading from Hannah Arendt’s “Elements and Origins of Total Domination”. Since then, the network has not only been a political association of artists, but also an archive, news exchange, contact point and sponsor (Instar awards grants and art prizes). A total of ten exhibitions by censored Cuban artists will be installed in the exhibition rooms in the Documenta Hall for ten days each. For Instar, their visibility is more than an aesthetic asset, but rather an emphatic political resistance in a society where, according to the companion book, the cultural sector has become an agent of change.

Graziela Kunsch

It is certainly one of the most radical projects of this Documenta: the “Parents and Infants’ Nursery”, which Graziela Kunsch set up consistently according to the maxims of an autonomy-oriented upbringing and in the spirit of the Hungarian pediatrician Emmi Pikler. The room is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the event and is intended to give toddlers the opportunity to look after themselves. While, as the artist hopes, the parents “perhaps learn more from our babies and from each other than we teach the babies”.

The bright hall, furnished with wooden fittings, is the most beautiful classroom in the Fridskul. Swings made of brightly colored fabrics hang above the expansive sandpit, and restrained, framed black-and-white photographs on the walls are reminiscent of the Hungarian orphanage that was run according to the Pikler maxims. In between there are a couple of wicker rattles and colorful cups. However, the room is closed to visitors during the day, and the art public may only enter the utopia after the pick-up time.