In 1994, when I was 10, my most reliable babysitter—a hexagonal television set with two antennae—introduced me to the concept of abortion. My cousins and I sat on the couch—our legs, clammy in the Miami heat, stuck to the plastic-covered furniture. There we watched the 1987 film Dirty Dancing. Even then, I understood the 1960s American class markers: the summer holiday resort, the pleasant cabins around a pristine lake, the employees serving the wealthy guests. But the scene I remember most was when Penny, a dance instructor, sat on the kitchen floor at night in tears and realized she had gotten into “trouble.”

“Trouble for what?” I wondered. My older cousins explained: Penny was pregnant, and an unplanned birth was the worst tragedy. It might have been less of a problem for the wealthy guests, but for someone like Penny, it could be life-threatening. The film is set in 1963, a decade before Roe v. Wade. Penny can’t afford to terminate the pregnancy or hold Robbie, the womanizer from Yale who impregnated her, accountable. She has to rely on the goodwill of her childhood friend and coworker, Johnny Castle, and a guest, Frances. Penny finally gets an abortion, but viewers learn that the doctor botched the procedure, and she barely survives.

The message was straightforward: Before Roe, one needed money and a sympathetic doctor to get a safe abortion. If you were poor and pregnant, you might face hardship and even death if you sought out cheaper and less experienced abortion providers. For many people, this reflected the reality. In 1965, according to Planned Parenthood, 17 percent of pregnancy-related deaths were due to unsafe abortions.

Dirty Dancing illustrated why access to safe abortions is so crucial. Penny, who is white, is a likable working-class figure. Yet the film neglected to show how working-class nonwhite women like me could access abortion. (My public education in Florida also wasn’t helpful on that score.) Penny could not get an abortion without a coterie of friends—and she wasn’t able to get a safe one.

When our parents and schools fail us, we have to rely on our personal networks and ourselves to find out what we must do to have jurisdiction over our bodies. This is why movies and books are so essential; even when the narratives are muffled or distorted, they contain lessons that circulate in our culture. And many of the most poignant stories about abortions are not on film; they’re in books—novels and short stories—that show us how we can talk about women, especially working-class women, who unapologetically end their pregnancies.

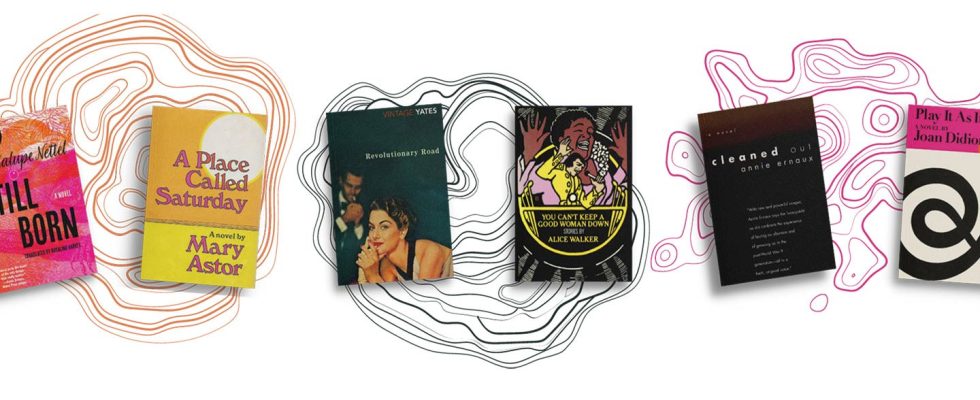

The decades preceding Roe saw a surge in abortion narratives in literature. In some cases, abortion was presented as a potentially fatal situation, as in Richard Yates’s 1961 novel Revolutionary Road, in which a woman dies after performing an abortion on herself; Mary Astor’s A Place Called Saturday from 1968, in which a male partner pressures the protagonist, Cora March, to have an abortion; and 1970’s Play It as It Lays by Joan Didion, in which an actress has an abortion that contributes to her psychiatric breakdown. Very few works portray working-class women from this period who terminate their pregnancies without regret or anguish.

There are, however, some important exceptions, including Alice Walker’s short story “The Abortion,” first published in 1980, and Annie Ernaux’s 1974 novel Les Armoires vides, or Cleaned Out—both of which take place before abortion was legalized in their authors’ countries (the United States and France, respectively), and both of which depict abortion from the point of view of women from modest backgrounds. Perhaps more crucially, Walker and Ernaux created characters whose decisions to have abortions are unclouded by doubt. These stories hew closer to how most women describe their abortions. About 75 percent of people who end their pregnancies are low-income. And when researchers studied the mental health and well-being of women who have had abortions, they found that 95 percent believed that they had made the right decision.

Writing the abortion stories of working-class women with tenderness and exacting honesty, as Walker and Ernaux do, is essential to the reproductive rights movement. It helps paint realistic portraits of people who seek abortions, thwarting right-wing stereotypes and teaching readers the liberatory possibilities of making one’s own reproductive choices.

In “The Abortion,” Alice Walker applies her formidable prose to the story of an African American woman seeking to terminate her pregnancy. It appears in her collection You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down, a reference to a Mamie Smith and Perry Bradford song. The book, a meditation on the trials and tribulations of Black women, explores love, culture, fame, and despair. “The Abortion” focuses on Imani, a young Black mother living in the South who is depressed and fatigued by marriage, motherhood, and pregnancy.

Facing an unwanted pregnancy, Imani lays out the toll of having and raising a Black child in America. Much of the story is devoted to what gestation does to the body: “Imani felt her body had been assaulted by these events and was, in fact, considerably weakened, and was also, in any case, chronically anemic and run down.” Imani already has a toddler and feels that being a parent is interfering with the life she wants to lead. “Another child would kill me,” she says. “I can’t imagine life with two kids.” So she discusses terminating the pregnancy with her husband, a lawyer named Clarence.

In the story, Imani has two abortions—one before her marriage and the other after she had her child, a daughter. Her first abortion was a clandestine procedure that cost a “thousand dollars, for which she would be in debt for years” and after which she hemorrhaged for weeks, while her second abortion was “seventy-five dollars…safe, quick, painless.” The story, which is clearly set before Roe, reflects the shifting legal landscape. Although abortion remained technically illegal in New York State, it was decriminalized in 1970 by the state Legislature. The result is that Imani’s second abortion is a relatively pedestrian event—a safe, standardized medical procedure.

“The Abortion” isn’t just an abortion story; it’s about the lives and deaths of working-class African Americans. It details Black subjugation at the height of civil unrest—in this case, on the fifth anniversary of the death of Holly Monroe, a fictional African American girl who was murdered after attending her high school graduation. Walker writes that Monroe was “aborted on the eve of becoming herself.” For Imani—and for contemporary readers—Monroe’s death is a gutting reminder that Black children’s lives can be cut short. Monroe’s memorial makes Imani realize that raising another Black child would only increase the probability of her having to mourn the untimely death of one of her own kids.

Walker’s story echoes her own life. Like Imani, Walker had a young daughter and a lawyer husband, and she would also have two abortions in the years before Roe. Both Walker and her character were concerned about the cruelty that society often metes out to Black people. Decades later, writing about her second abortion, Walker explained:

We knew the children being fire-hosed were innocent of anything but being children struggling for a future. We knew the beatings, car bombings, explosions, house and church burnings, and violent assassinations were intimations of a future that more and more is coming to pass. To bring anyone, especially a helpless infant, into what was clearly a destructive situation, in a world where few in power even pretended to care for children of color, seemed the very definition of madness.

What Walker shows us is that one of the major promises of motherhood is a lie: One will not necessarily be fulfilled or content just by being a parent. Imani, however, insists on holding on to truth. She tells her toddler that white people “think they can kill a continent—people, trees, buffalo—and then fly off to the moon and just forget about it. But you and me, we’re going to remember the people, the trees and the fucking buffalo.” The toddler, mimicking her mother, responds, “Buffwoe.” Here, Imani is attentive to oppressed people, animals, and nature, indicating that the decision to be a parent is not merely about physical care but about cultivating a political education. Walker’s story is a departure from a significant portion of the abortion literature precisely because it exposes the racial hierarchies of life and the power of historical memory.

Imani is unwavering in her decision. The narrator tells the reader that “their aborted child would have been a troublesome, ‘terrible’ two-year-old, a great burden on its mother, whose health was by now in excellent shape.” Parenting wears down mothers, and deciding to abort can be a decision to prioritize one’s body and political integrity.

One of the richest accounts of an abortion by a working-class woman is Annie Ernaux’s Cleaned Out. Published in 1974, it chronicles the experience of Denise Lesur, a 20-year-old French scholarship student. From the description of her body and the accounts of her village, the reader quickly recognizes in Denise a storyteller intent on protecting her future at any cost. The opening scene is striking:

I was on the table, all I would see between my legs was her grey hair and the red snake she was brandishing with a pair of forceps. It disappeared. Unbearable pain. I shouted at the old woman who was stuffing in cotton wool to keep it in place. Shouldn’t touch yourself down there, it’ll get damaged.

The “snake” inserted into Denise is a tube, which she has to keep inside her all day to terminate the gestation. The whole time, her body is wracked by spasms of horrific pain, a constant reminder that she has just had “a backstreet abortion.” A poetic sensibility pervades the book, with Ernaux tracing Denise’s sensory journey: “My head pressed into the smell of the blanket, the sun beating down on me from my waist to my knees, a warm tide inside me, not a wrinkle visible, everything is taking place in folds and crevices miles below the surface.”

As in Walker’s short story, the illegal abortion is not only a secret affair but a costly one, requiring Denise to secure funds far beyond what she can afford. This is a central issue for Denise, the ambitious daughter of a storekeeper. Aspiring to enter the world of arts and letters, she is aware that class is determined by more than education—it is a sense of belonging that is alien to her. Denise feels “clumsy and awkward in comparison with the private-school girls, who are confident, who know just what to do.” Likewise, the story of her abortion is not just about the physical procedure but about the disdain she feels for her upper-class classmates as she tries to move up the class hierarchy. Her abortion becomes a way to secure her future, even if the postoperative symptoms cause her pain.

This novel, too, was based on the author’s abortion experience, and it shows how desperate working-class French women were to access the procedure before it was legalized in France in 1975. In her 2000 memoir, L’Événement (Happening), Ernaux tells the story of her pursuit of an abortion. She seeks a physician. She asks her lover for money to terminate the pregnancy, and he tries to have sex with her. She even tries to induce an abortion herself. But the story isn’t just about choice; it’s about class shame, which fuels her desire to succeed. For Ernaux, having a child at that time would have prevented her from eventually becoming a Nobel Prize–winning author.

Writing to her translator, Carol Sander, Ernaux asserts, “There is in Les Armoires vides a desire to transgress all boundaries. In its content: saying the unsayable, feeling ashamed of one’s parents, humiliated, wanting to be like everyone else; speaking about the female body, menstruation, erotic pleasure, abortion.” Like Walker, Ernaux was not stifled by the stigma of abortion; instead, the procedure was a path to liberation.

Part of the beauty of art is that we can recognize bits of ourselves in it. Like Penny in Dirty Dancing, I grew up poor and knew what it was like to rely on friends for survival. While I never saw any reason for Penny to feel chagrin for her abortion, I internalized the film’s message that an unwanted pregnancy was a life-shattering problem, especially if you were poor.

Walker and Ernaux moved past this discourse. They showed how abortion literature could render the interests of working-class women without relegating them to mere troublemakers. Their characters didn’t rely on benefactors or do as others wished; they pushed the plot forward themselves. In Walker and Ernaux’s telling, abortion is freeing. As Imani affirmed, abortion can be a “seizing of the direction of her own life.”

Today there are even more radical accounts of reproductive choices in literature. In Guadalupe Nettel’s novel Still Born, published in 2020, Laura, the protagonist, presents an unflinching desire not to have children. When she contemplated having a kid, Laura recognized her error: “Just as someone who, without ever having contemplated suicide, allows themselves to be seduced by the abyss from the top of a skyscraper, I felt the lure of pregnancy.” So, early in the text, Laura gets her tubes tied. I loved the book’s energy and comic style. Unlike the typical abortion plots that spend so much time probing a character’s troubles, Nettel’s novel offers a thrilling possibility: opting out of motherhood altogether. A profound message binds Nettel’s novel with Walker’s and Ernaux’s work: the desire to live fully.

Given the attacks on reproductive rights around the world, abortion narratives will continue to offer nuance when it comes to issues of representation and access, and now a new generation of authors, including Nettel, are building on the literary breakthroughs of Walker and Ernaux, choosing to write about women who make their own choices without apology.