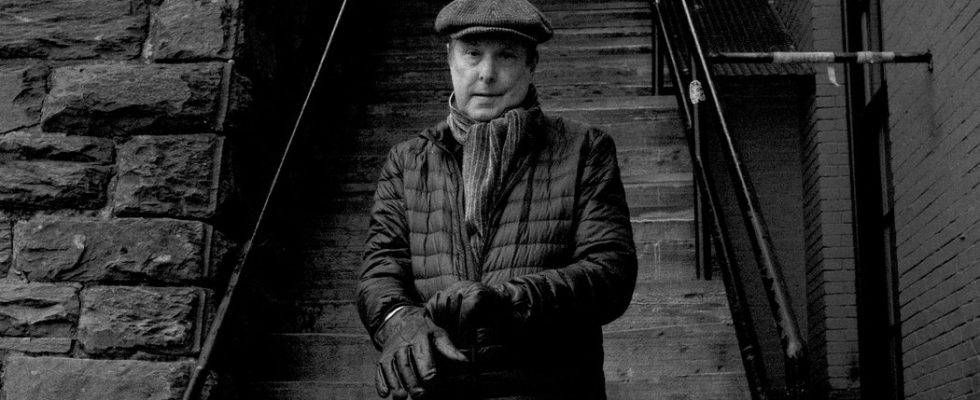

William Friedkin, a filmmaker whose gritty, visceral style and fascination with characters on the edge helped make “The French Connection” and “The Exorcist” two of the biggest box-office hits of the 1970s, died on Monday at his home in the Bel Air neighborhood of Los Angeles. He was 87.

The cause was heart failure and pneumonia, said his wife, Sherry Lansing, the former head of Paramount Pictures in Hollywood. Mr. Friedkin recently directed “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” a movie, yet to be released, based on the Herman Wouk play.

Mr. Friedkin was a promising but not well-known director with a background in documentary film when he teamed up with the producer Philip D’Antoni to make “The French Connection,” based on the true story of two swashbuckling New York City police officers, Sonny Grosso and Eddie Egan, who broke up an international heroin-trafficking ring in 1961. The script was adapted from a book by Robin Moore.

Working with a modest budget, Mr. Friedkin and Mr. D’Antoni relied on a cast of relative unknowns. Roy Scheider, an Off Broadway actor, took the role of Mr. Grosso, called Buddy Russo in the film. Gene Hackman, whose modest credits included a small part in a big film, “Bonnie and Clyde,” and a big part in a small film, “I Never Sang for My Father,” was hired to play his partner, Popeye Doyle, based on Mr. Egan.

By sheer accident, Fernando Rey played Alain Charnier, a character based on the international drug kingpin Jean Jehan. Mr. Friedkin had wanted Francisco Rabal, from the Luis Buñuel film “Belle de Jour,” but his casting director confused the two actors.

Filmed on location in New York for less than $2 million, or about $15 million in today’s money (the average Hollywood film cost $3 million at the time), “The French Connection” delivered visceral drama, documentary realism and edge-of-your-seat thrills. Popeye Doyle’s pursuit, in a commandeered car, of a hijacked elevated train in Brooklyn has often been called the best car-chase scene ever filmed.

“The French Connection” was released in 1971 and dominated the Academy Awards the next year, winning the Oscar for best picture and earning Mr. Friedkin the best director award. Mr. Hackman won for best actor in a leading role. The film also won in the adapted screenplay and editing categories.

Mr. Friedkin followed up a year later with “The Exorcist,” based on William Peter Blatty’s best-selling horror novel about the demonic possession of a 12-year-old girl. Filmed largely on location in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, it was a suspenseful, often gruesome, cinematic study of evil at work in the modern world — evil conceived in almost medieval terms.

Linda Blair, as the possessed girl, gave a terrifying performance enhanced by eye-popping special effects. In a cinematic moment that entered into legend, she spewed a jet of green vomit — actually a blend of oatmeal and pea soup — straight into the face of a priest played by Jason Miller. Even more startling, during the exorcism later in the film, her head spun full circle on her shoulders, grinning maniacally.

The film, released in late December 1973, became a phenomenal hit, one of Hollywood’s top-grossing movies to date, with ticket sales of more than $200 million (the equivalent of about $1.3 billion today). It was also the first horror film to be nominated for a best picture Oscar. (It lost to “The Sting.”)

In New York, audiences lined up for hours in the freezing cold, while scalpers sold tickets for three times their face value. Vincent Canby, in The New York Times, dismissed the film as “claptrap” but pronounced it “the biggest thing to hit the industry since Mary Pickford, popcorn, pornography and ‘The Godfather.’”

The ripple effects from both films lasted for decades. “The French Connection” injected realism and violence into hard-boiled thrillers like the “Dirty Harry” films and television police series like “Hill Street Blues,” while “The Exorcist” changed critical attitudes toward horror films.

“Horror was a disreputable genre, but Friedkin elevated it with the A-list treatment,” Peter Biskind, the author of “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ’n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood” (1998), said in an interview for this obituary in 2016. “‘The Exorcist’ was so successful that it paved the way for the gentrification of B movies that has given us ‘Star Wars,’ the ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ cycle and the comic-book movies we have today.”

William Friedkin, known to his friends as Billy, was born in Chicago on Aug. 25, 1935, to Louis and Rachel (Green) Friedkin. Both parents were Jews who had left Ukraine early in the century with their families to escape the tsarist pogroms. His mother, who was known as Rae, was an operating room nurse; his father worked a variety of low-paying jobs.

After graduating from Senn High School on Chicago’s North Side in 1953, Mr. Friedkin took a job in the mailroom of the local television station WGN. Within a few years he had worked his way up to director, turning out hundreds of shows, from “Bozo’s Circus” to live performances of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as well as documentaries.

His documentary work coincided with the advent of portable cameras, a decisive influence on his style. “I learned on equipment that almost begged for you to get up and move around,” he told Gene Siskel, the film critic for The Chicago Tribune, in 1980.

After his documentary “The People vs. Paul Crump,” about a death-row prisoner in the Cook County Jail, won the grand prize at the San Francisco Film Festival in 1962, Mr. Friedkin went to work in Los Angeles for David Wolper, a producer of documentaries for all three television networks.

Mr. Friedkin’s first assignment as a feature-film director was a Sonny and Cher vehicle, “Good Times” (1967), which impressed critics with its cheery bounce and inventive camera work. He followed with “The Birthday Party” (1968), a film version of the Harold Pinter play, with Robert Shaw in the lead role, and “The Night They Raided Minsky’s” (1968), an odd knockabout period piece about the burlesque era. He returned to theatrical source material with “The Boys in the Band” (1970), Mart Crowley’s Off Broadway hit about seven gay friends reflecting on their lives and loves.

“The French Connection” was rejected by every studio in town before Richard Zanuck, in his final days at 20th Century Fox, gave it the green light. Convinced that the film required a street-level documentary feel, Mr. Friedkin spent weeks on the beat with the two police officers who had broken the French Connection drug case. He said he paid an official at the New York Transit Authority a $40,000 bribe to overlook the rules and allow the famous chase sequence to be filmed.

After “The French Connection” won five Oscars and “The Exorcist” became an enormous box-office success, Mr. Friedkin found himself one of the most sought-after directors in Hollywood.

A turbulent period ensued. He remade “The Wages of Fear,” Henri-Georges Clouzot’s classic 1953 thriller about drifters driving truckloads of nitroglycerin over rugged terrain, as “Sorcerer” (1977), with Mr. Scheider in the part originally played by Yves Montand. Most critics found it long, labored and not particularly thrilling. It was released around the same time as “Star Wars” and died a quick death.

He later called “Sorcerer,” in an interview with Indiewire in 2017, “the only film I’ve made that I can still watch.”

The lurid “Cruising” (1980), with Al Pacino as a New York City detective who goes undercover in the city’s gay S-and-M bars to solve a murder, aroused the fierce opposition of gay activists, who objected to the film’s portrayal of gay men and who picketed the location shoots, much to Mr. Friedkin’s dismay.

That film was the first in a series of flops that included “Deal of the Century” (1983), a farce about arms dealers, with Chevy Chase, Gregory Hines and Sigourney Weaver, and the critically reviled “Jade” (1995), a murder mystery with a script by Joe Eszterhas and with Linda Fiorentino and David Caruso in the starring roles. Along the way, Mr. Friedkin managed something like a return to form with “To Live and Die in L.A.” (1985), an atmospheric noir about a Secret Service agent seeking to avenge the death of his partner.

“The paradox of William Friedkin is that he made only two really good films, ‘The French Connection’ and ‘The Exorcist,’” Mr. Biskind said. “There are others that are interesting but deeply flawed. But those two films had an outsize influence.”

Mr. Friedkin married Ms. Lansing in 1991. She was the chairman and chief executive of Paramount Pictures from 1992 to 2005. His first three marriages — to the actresses Jeanne Moreau and Lesley-Anne Down and the television news anchor Kelly Lange — ended in divorce. In addition to Ms. Lansing, he is survived by two sons, Jackson and Cedric.

After years in the professional wilderness, Mr. Friedkin won positive reviews for two courtroom dramas: a 1997 television remake of “Twelve Angry Men,” with Jack Lemmon, George C. Scott and Hume Cronyn; and “Rules of Engagement” (2000), with Tommy Lee Jones and Samuel L. Jackson.

He went on to direct several well-received small films, two of them based on plays by Tracy Letts: “Bug” (2006), a study in horror and delusion, and “Killer Joe” (2011), the sordid tale of a murder-for-hire plot that takes a strange turn when the hit man, played by Matthew McConaughey, enters the picture.

In 2013, Mr. Friedkin was awarded a Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement at the Venice Film Festival. That same year, Harper published his book “The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir.”

Late in his career, he returned to familiar territory with “The Devil and Father Amorth” (2017), a documentary account of an exorcism performed in an Italian village by the Vatican’s chief exorcist.

His most recent effort, “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” starring Kiefer Sutherland and Jason Clarke, will have its premier at the Venice Film Festival, which begins on Aug. 30, Ms. Lansing said.

For all his groundbreaking work, Mr. Friedkin remained modest about it. “I don’t see myself as a pioneer,” he told The Independent in 2012. “I see myself as a working guy and that’s all, and that is enough.”

Ashley Shannon Wu contributed reporting.