When it comes to understanding modern politics, analogies abound. We have the 1938 Munich conference as a metaphor for the perils of being “weak” on foreign policy. Modern hyper-partisanship has driven comparisons to the 1850s and the lead-up to the Civil War. With the combination of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, and a new wave of strikes roiling the nation, scholars and journalists have compared our current moment to the 1918 influenza pandemic and the following year’s Red Summer, when the United States appeared to be on fire with strikes and protests from coast to coast.

One of the most potent analogies has been that of Reconstruction. The term was coined during the Civil War to describe the plan to readmit the secessionist states and push the South to transition to a post-slavery economy. It took on a new life in the 1950s and ’60s, when civil rights activists and observers began to refer to a “Second Reconstruction.” For them, the first had been an incomplete revolution: Black men gained the right to vote and Black people in general became—however fitfully—part of the American body politic, but these gains were soon dismantled by white Southern violence and political intimidation and white Northern indifference. The radicals of the 1950s and ’60s set out to try again, hoping to both expand and finish the job of the first Reconstruction 100 years later. In his famous speech in Montgomery, Ala., celebrating the culmination of the Selma to Montgomery marches and the 1965 voting rights campaign, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. laid out the case for the importance of the first Reconstruction and the urgent need for a second one. Describing the end of Reconstruction as a “travesty of justice,” King stated in defiance of Southern segregationists that “we are on the move now.”

Much was achieved during this Second Reconstruction, but like the first it remained unfinished. The economic disparities between Black and white Americans continued to be a major problem. Meanwhile, an ascendant right challenged the victories of the civil rights movement, even as legal segregation was destroyed. As C. Vann Woodward, the eminent historian of the South, presciently noted in a 1965 essay in Harper’s, there would likely come a time when the American polis would recognize the need for a Third Reconstruction. Woodward revised and republished the Harper’s piece in a book of essays, The Burden of Southern History, in 1968. “It may be that in due course,” Woodward wrote, “say on the eve of the Third Reconstruction, some enterprising historian will bring out a monograph on the Compromise that ended the Second Reconstruction, entitled perhaps The Triumph of Tokenism.”

Woodward’s premonition comes to mind when reading Peniel Joseph’s new book, The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century. A scholar of the Black Power movement, Joseph turns his attention here to Black America’s plight since the beginning of the 1980s. For Joseph, not to mention many others, the need to reckon with the history of the last 40 years is paramount if we are to finally complete the work of Reconstruction. Inspired by the events of Barack Obama’s presidency, the rise of Black Lives Matter in the 2010s, the crises of Covid and the January 6 insurrection, and his own early life experiences, Joseph offers a book that seeks to understand the post–civil rights history of Black America.

The origins of his career as a historian, Joseph tells us, can be found in the classrooms of New York City in the 1980s and in his home, growing up with a mother of Haitian descent. He could not understand how life could be so difficult for the young men and women who looked like him when, at the same time, the teachers at his Catholic school were telling him and the other students of the greatness of America during and after the civil rights movement. “I began to notice this gap in our perceptions,” Joseph writes, explaining in a short but powerful statement what it means to be Black in America. The promise of the civil rights and Black Power era remained unfulfilled, and so Black Americans—and the rest of the country—needed to renew the struggle to secure what the Reconstructions of the past had tried but failed to achieve.

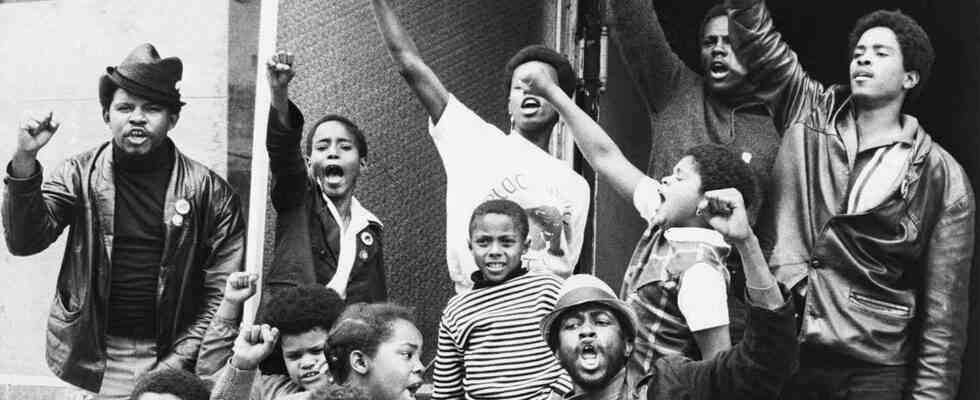

Joseph has spent much of his career pushing Americans to reexamine what they think they know about the Black Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s. Currently, he serves in several roles at the University of Texas at Austin: as the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values; as an associate dean for justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion; and as the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. His first book, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, was a landmark text that tied together the resurgence of Black nationalism in the 1950s and the rise of the Nation of Islam in the early 1960s, the Black Panthers in the late ’60s, and the Pan-Africanists in the 1970s.

Since then, Joseph has written about such figures as Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) in Stokely: A Life and argued against accounts that posit a simplistic and ideologically hostile relationship between MLK and Malcolm X in The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In his 2010 work Dark Days, Bright Nights: From Black Power to Barack Obama, Joseph explored how the post–Voting Rights Act era became a radical moment of political, cultural, and intellectual debate among Black Americans.

Now, in The Third Reconstruction, Joseph extends his work on Black Power and Black life in post–World War II America to the present by insisting that a clear understanding of the 1980s and ’90s is necessary to grasp the current social movements for freedom in America. In many ways, The Third Reconstruction expands and develops the arguments found in Manning Marable’s Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction and Beyond in Black America. Revised several times, with its subtitle changing to reflect the updates, Marable’s book tracks the growing frustration with the achievements of the civil rights movement among a new generation of Black scholars and activists. The first edition was released in 1984, the second in 1991. By 2007, when the third (and final) edition was published, Marable had had time to reflect on how much his own thinking had changed in the past 25 years. In the book’s first edition, he argued that by 1982, the civil rights gains of the ’60s and ’70s were under threat from “the triumph of Reaganism.” In a revised chapter for the 1991 edition, Marable argued that “in many respects the state of American race relations reached a new nadir in the late 1980s and early 1990s.” By the 21st century, he was offering an even grimmer view: After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, he could see that his earlier assessments had not fully appreciated how much work was still needed to fix the United States. “The awful specter of black bodies floating in New Orleans,” he wrote, “of hundreds of thousands being dispersed throughout the country and being denied constructive federal aid, underscored just how enduring the great racial and class divides are within the fabric and logic of American institutions of power.”

In many ways, Joseph picks up where Marable left off. Reflecting on the difficulty of the historical parallels he hopes to draw in The Third Reconstruction, he agrees with Marable that the two earlier Reconstructions did not go far enough. While the country’s problems in the 1970s and ’80s weren’t the same as those in the 1870s, Joseph does note some troubling parallels. In the 1860s and ’70s, the brief hopeful period of Reconstruction was overwhelmed by the long era of Redemption and then by Jim Crow segregation, while in the 1960s and ’70s, the country saw the destruction of most Black radical political organizations, the assassination of numerous Black leaders, and a broader right-wing attack on the achievements of the civil rights and Black Power movements. Figures like Julian Bond, an activist turned Democratic Party politician in Georgia, repeatedly lamented the erosion of these gains in the late 1970s and the ’80s, especially during Ronald Reagan’s presidency. In 1982, Bond argued against Reagan’s attempt to weaken the Voting Rights Act that year, saying: “If the president prevails, voting rights will perish, and black Americans will be a voteless—and a hopeless—people once again.”

Joseph experienced firsthand the on-the-ground stakes of this reality. Coming of age during the Reagan era, he grew up in a New York City that was defined by Reagan’s conservatism on race and the welfare state, along with an expanding War on Drugs. For Joseph, Barack Obama’s election in 2008 represented the promise of “a new vision of US citizenship,” one that would live up to the nation’s greatest statements on freedom and democracy. Instead, Joseph argues, Trump’s election after the Obama era became a reminder that “white backlash contains multitudes.” But the Obama years also ushered in the Black Lives Matter movement, which continued the long Black radical tradition of keeping America honest about its many issues with race and democracy.

One of the strengths of The Third Reconstruction is how carefully Joseph captures the history that was taking place during his adolescence. He spares no one among the country’s political leaders, criticizing Democratic presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton for their inability to escape the neo-Redemptionist ideas inherent in the “law and order” rhetoric popularized by Richard Nixon in the late 1960s. The frustrations with Carter in the late 1970s among Black leaders and lay citizens alike, Joseph notes, were early warnings about the lack of progress for Black Americans after the civil rights era. Clinton, of course, proved far worse: He used his own brand of law-and-order politics, crafted by the Democratic Leadership Council and the party’s moderate wing, to propel the Democrats back into the White House after 12 years in the political wilderness. “A bipartisan consensus forged in the maelstrom of America’s Second Reconstruction,” Joseph writes, “substituted racially charged symbols—of crime, drug addiction, welfare, public schools, the King holiday—over dismantling structural racism.”

For Joseph, all of this appeared to be changing with Obama’s election, given how much he had spoken of the need to take action on the long-festering issues of racial inequality. But very quickly, Joseph notes, Obama’s vision of hope began to collide with political realities: His call for “national unity became entangled with the cords of America’s racial past, which hindered its fulfillment in both new and tragically familiar ways.” Obama needed to take bold and decisive action to address the nation’s political, social, and cultural wounds, and yet he did the exact opposite. The actions needed to remake the United States into a true democracy would be difficult, and Obama proved unwilling to embrace the conflict that would come with it. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement marked a growing frustration with Obama, but as Joseph observes, the few gains that were won during the Obama years also created a space for the rise of a white nationalism that found its voice in Donald Trump. “Seeking to redeem America from the scourge of Black equality,” Joseph writes, “Trump and his supporters looked less to Nixon than to the Reconstruction-era South Carolina demagogue Ben Tillman and his violent supporters.”

Joseph compares Trump’s neo-Redemptionist rise with that of Tillman, who became South Carolina’s governor and later senator. Working as part of the “Red Shirts” in the 1870s, Tillman led the white supremacist violence that disrupted and ultimately destroyed Black political power in the state for generations. As South Carolina’s governor in the 1890s, he spearheaded the effort to draft a new state constitution that would end Black voting rights without technically violating the language of the new 14th and 15th amendments to the US Constitution. The 1895 state Constitution would do just that, replacing the more progressive 1868 Constitution adopted during Reconstruction. In a speech on the floor of the US Senate in 1900, Tillman boasted that this suppression of Black votes was his goal: “Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took up the matter calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disenfranchising as many of them as we could under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.”

Trump did not seek to completely dismantle Black voting rights, nor was he as successful at achieving the frightening rollback of basic freedoms that Tillman and his followers sought. But he did “normalize white supremacy in contemporary American politics,” Joseph notes, through his lukewarm response to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, where one person was killed and dozens more injured in a car attack on the anti-racist counterprotesters, as well as through his utilization of the kind of white supremacist rhetoric once consigned to the margins of the far right.

Placing Trump in the tradition of Tillman, as well as the massacre in Hamburg, S.C., in 1876 and the Wilmington Coup of 1898, makes clear how dangerous he is not just to Black Americans but to the basic ideas of democracy, self-determination, and civil and political rights. But that means we should also reconsider whether this is indeed a Third Reconstruction or, potentially, another reversal in the struggle for Black freedom and equality. In 2010, The Black Scholar published “The New Nadir: The Contemporary Black Racial Formation,” by the historian Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua, in which he argued that despite the election of the nation’s first Black president, the material conditions of Black Americans had only gotten worse in the wake of the Great Recession of 2009. “What is needed,” Cha-Jua concluded, “is a political strategy and a social movement that seek to coordinate and redeploy blacks’ social capital to rebuild, revitalize, and democratize black civil society.” Joseph agrees: What Cha-Jua, and Marable before him, diagnosed as the failures of the first two Reconstructions demands the success of a new one.

Throughout The Third Reconstruction, Joseph compares Black Lives Matter to the civil rights and Black Power movements. Referring to the protests that swept the nation in 2020 after George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, Joseph writes: “Black equality as the beating heart of American democracy proved to be the central message behind the largest social justice mobilization in American history.” But what makes Black Lives Matter different, in his estimation, is that by “shedding the political shortcomings that had plagued the two earlier periods of Reconstruction,” it was able to “embrac[e] the full complexity of Black identity.”

Joseph takes pains to honor the Black women and the members of the LGBTQ community who have been instrumental in today’s social movements. That Black Lives Matter has done so too, he argues, is one of its greatest strengths and gives him cause not to despair. We must not be shackled by the past, he declares, but at the same time, the past gives us reason to imagine a better future—one defined by a Reconstruction that has lasting power. “Today, in the midst of another period of Reconstruction,” Joseph writes, “we have a grave political and moral choice to make. I choose hope.”