In the November 2nd election for New Jersey’s Third Senate District, the Democrat, Steve Sweeney, had twenty years of incumbency on his side, including twelve years as State Senate president—the longest tenure in that position in state history. A self-described social moderate and fiscal conservative, he has been an ally of George Norcross, an insurance executive and the longtime political boss of South Jersey. Sweeney thrived working opposite governors of both parties, cutting deals with Chris Christie and acting as a check on some of the more progressive ambitions of the current Democratic governor, Phil Murphy. In 2017, when Sweeney was last up for reëlection, New Jersey’s largest teacher’s union, angered by his opposition to increased spending on public-employee pensions, spent more than five million dollars in an attempt to unseat him. The Third District’s voters reëlected Sweeney by eighteen points.

This year, Sweeney’s Republican challenger was Ed Durr, a fifty-eight-year-old truck driver for Raymour & Flanigan, the furniture chain. Durr, who ran unsuccessfully for the state assembly in 2017 and 2019, has said that he was originally motivated to seek office to loosen the state’s gun-control laws. Leading up to the election, he had spent only a few thousand dollars on the race. He shot a campaign video using a cell phone, and the state Republican Party never officially endorsed him. Durr beat Sweeney by three points, the equivalent of some two thousand votes, thanks to a late surge of Republican voter enthusiasm that brought down several Democratic candidates in the state and forced Murphy to sweat out a closer-than-expected victory.

Durr’s victory attracted instant media attention. The press camped outside his house, in Logan Township, and tweeted about him walking his three pit bulls. He appeared on Fox News, and turned down an interview request from the Times. The Atlantic worried what his victory meant for populism, while the Washington Post wondered what it said about the state of local news. “Saturday Night Live” made fun of his last name. (“Coincidentally, ‘Durr’ is also the New Jersey state motto,” Michael Che said, grinning, during a “Weekend Update” segment.) Former President Donald Trump called to speak with him directly. (“Anything I can do, you let me know, O.K.?” Trump told him. “Thank you very much, sir,” Durr responded. “And you know you can call me at any time.”)

New Jersey’s political class was stunned. “I don’t know what happened,” Loretta Weinberg, the Democratic majority leader in the State Senate, who has served in the legislature since 1992, said. Of the Third District’s voters, she added, “I’m not sure that they know who they voted for.” Speaking to the Times, Norcross sounded defensive. “There was nothing that could have been anticipated or done,” he said. “It’s not like we didn’t have the money available to do it.” One South Jersey Republican called Durr’s victory “the biggest thing that has ever happened in Jersey, and will ever happen in Jersey politically.” Durr himself seemed most stunned of all. “I joked with people and I said, ‘I’m going to shock the world. I’m going to beat this man,’ ” Durr told a reporter. “I was saying it but really kind of joking. Because what chance did a person like me really stand against this man?”

And then reporters began combing through Durr’s social-media posts. “Mohammed was a pedophile!” he tweeted, in September, 2019. “Islam is a false religion! Only fools follow muslim teachings! It is a cult of hate!” In other posts, he argued that there had been “thugs” on “both sides” of the 2017 white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; compared COVID-19-vaccine mandates to the Holocaust; referred to Chelsea Manning, the trans activist and government whistle-blower, as “shim”; and suggested that Kamala Harris had only reached the office of Vice-President because of her race and gender. The January 6th riot at the U.S. Capitol, he wrote on Facebook, earlier this year, was “not an insurrection” but “an unauthorized entry by undocumented federal employers!” His Twitter and Facebook accounts soon came down. Three days after the election, he issued an apology. “I’m a passionate guy and I sometimes say things in the heat of the moment,” he said. “If I said things in the past that hurt anybody’s feelings, I sincerely apologize.” That same day, he was back at work, driving his truck. He’d used up his vacation time during the election.

Last week, I visited the Raymour & Flanigan distribution center in Gibbstown, New Jersey, where Durr works. It was easy to find people who spoke of his election with a touch of awe in their voice. One young man, smoking a cigarette in the parking lot, asked if I was looking for Ed Durr the father or the son. (Durr’s son works at the same facility.) A few minutes’ drive away, Durr’s small blue house sits at the end of a winding road. His mother lives next door. His father, whom Durr credited with inspiring him to run for office, died just a few weeks ago. Durr recently told the Washington Examiner that his parents were both Kennedy Democrats who became Reagan Republicans. A motorcycle, an aging Ford Mustang, and an S.U.V. bearing “Edward Durr 4 Senate” stickers on its front doors were parked in Durr’s driveway. A Gadsden flag flew just below the Stars and Stripes on a flagpole. The interstate was visible just beyond the back yard. When I knocked on the door, I heard dogs going crazy. Someone pulled a window open. “Ed’s not here,” a woman said, wearily. As she closed the window, I heard her implore the dogs to relax.

Later that day, Durr was scheduled to meet with with Muslim community leaders, including Selaedin Maksut, the executive director of the New Jersey chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, at the Al-Minhal Academy for Islamic Education, in Sewell, a few towns over. (Shortly after Durr’s tweets surfaced, Maksut had issued a statement saying, “Mr. Durr will soon be a state senator in New Jersey, and so, I believe it is in everyone’s best interest to engage him in conversation and not let the matter go unchecked.”) In the parking lot, the sky turned purple and yellow as the sun went down over the strip malls. Local-news cameramen and reporters busied themselves with equipment checks and small talk. Several were incredulous that Sweeney’s campaign hadn’t uncovered Durr’s tweets before the election. “A thirty-second spot on TV for a week before Election Day probably would have sunk him,” one said, shaking his head. Another replied, “And Sweeney would have won, and we wouldn’t be here.”

A few people working at nearby businesses got curious about the TV-news vans and drove over to investigate. “What’s going on here?” Jeanne Levonchuck, the manager of a nearby store, asked me, from the driver’s seat of a gray sedan. She wore glasses and an American-flag lanyard around her neck, and smiled when she heard Durr’s name. I asked if she’d voted for him. “Well, let’s just say I didn’t vote for Sweeney,” Levonchuck said. She’d lived all her life in Gloucester County, in the Third District. She was a Trump fan—“I do miss Donald,” she said—and knew Sweeney from her time working for the Gloucester County Special Services School District. “He was the man who supposedly made the school,” she told me. She’d voted for him in the past, but not this year. “I don’t like the man,” she said. “He thought that he was a god. All terrible. Almighty.”

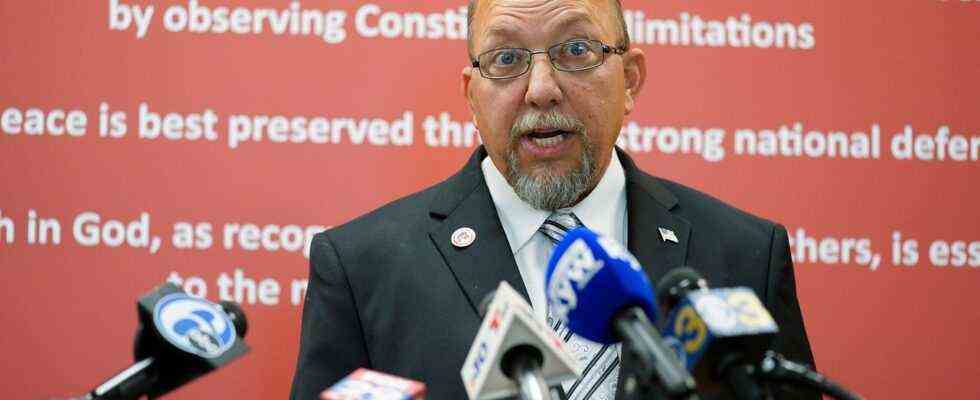

Around 6 P.M., Durr and Maksut walked out to the parking lot, trailed by a group of solemn-faced men and women. Maksut, in a blue sports coat, spoke first. “I just want to say thank you, Mr. Durr, for meeting us out here,” he said. “I think we had a very productive conversation.” Durr nodded. “I believe we made some progress,” Durr said. He seemed nervous, and spoke haltingly. In his hand, he held a Quran. “I just want to make the little statement to you guys, as far as this goes, as I reiterated to the group inside, that I stand against Islamophobia and all forms of hate,” he said. “And I do commit to that.” A reporter asked him what the discussion inside had been like. Durr said that it had been “open,” and that everyone in the room had been able to “get a sense of” one another. “It’s very easy to hate somebody that you don’t know,” Durr said. “But if you know them personally, and you talk to them—very hard to hate them. Don’t you think? That’s progress, right?” I asked Durr why he thought it was easy to hate people from a distance. “Because you just don’t know,” he said. “You’re in your own bubble.”

I approached Durr after the press conference. He said that he could give me two minutes—his wife was sick, and he’d been away from her for “a good five hours.” Then he asked me a question. “Do you like paying taxes?” he said. “Tell me you like paying taxes.” I told him that I appreciated what taxes paid for: subways, roads, schools, hospitals. Durr, who sports a well-kempt goatee, had removed his suit jacket and stood in suspenders. He furrowed his brow like I was the biggest chump he’d ever seen. “They don’t pay for all that,” he said, leaning toward me. “Your taxes go into people’s pockets.”

I mentioned police departments, trying to think of a government expenditure he might support. “There are things in the police department that need to be addressed, too, that are a waste,” Durr said. “I mean, there are wastes all over. You are not going to tell me that there isn’t waste.” I asked him what he thought his election meant. I’d been thinking of other notable political upsets, including Dave Brat’s Republican-primary victory over House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, of Virginia, in 2014, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s primary win over the House Democratic Caucus chair Joe Crowley, of New York, in 2018. Both had upended party power structures. Durr said he hadn’t been paying attention to politics back in Brat’s day, but that he would “equate” his election with Ocasio-Cortez’s, “even though she and I are politically different.”

On my drive home, I called Maksut, to hear more details about the meeting. “We explained to him our point of view,” he told me. “That this kind of hate speech can lead to violence.” Maksut said that he’d told Durr a story about his grandmother, who wears a hijab, being hit in the face with a purse at a shopping center in North Jersey. “My grandma’s been told to go home, back to her country, that she’s a terrorist, that she doesn’t speak English, even though she speaks seven different languages,” he said. The group had prayed while Durr was with them. “We prayed the evening prayer,” Maksut said. “He started asking questions about the religion. We started sharing stories about the Prophet Muhammad, who he called a pedophile.” I asked Maksut if he had a sense of where Durr had picked up this tired, hateful trope. “We can’t forget that Trump was President for four years,” he said. “The man who said, ‘I think Islam hates us.’ ”

On Thursday, I spoke with Sweeney on the phone. “It was a red tide,” he said. “That’s the only way to explain it.” He mentioned a recent NJ Advance Media analysis of his district, which showed that Republican registration went up some thirty per cent in the past four years, while Democratic registration rose only twelve per cent. Southwestern New Jersey is poorer, more rural, and whiter than other areas of the state—bad conditions lately for the Democratic Party. Sweeney had received about as many votes this year as he did when he won reëlection in 2017, but thousands of additional voters had come out. “My district has been a Republican district from the day I won it,” Sweeney said. “I would love to point at something like ‘I should have done this’ or ‘I really screwed up here.’ But it had nothing to do with it.”

One South Jersey Democrat told me that he thought Sweeney had been too focussed on helping other Democratic candidates, rather than focussing on his own race. Sweeney acknowledged that much of the money he had spent during the campaign had gone to help the two assembly members in his district—“We run as a team,” he said—and he bemoaned the loss of local news coverage. “We used to have local papers,” he said. “And people used to be able to read about all of these wonderful things that were going on.” Progressives in the state were looking at Sweeney’s defeat as evidence of the political dangers of centrism. Sweeney saw it the other way around. He talked about the minimum wage, paid family leave, and green-energy initiatives. “Listen, I’m not a progressive,” he said. “But Phil Murphy—not one piece of legislation that he championed didn’t get passed by me to get to him.”

On the subject of Durr, Sweeney felt strongly that voters in the Third District were simply voting for the Republican and against the Democrat. “It wasn’t a vote for someone,” he said. “It was a vote against someone.” Sweeney talked about his daughter, who has Down syndrome, and said that he’d got into politics in the first place to champion the rights of the disabled. I asked him how many people in his district he thought knew that. “In my mind, it wasn’t people saying, like, ‘I don’t like Steve Sweeney,’ ” he said. “I really don’t believe that. It was, ‘You guys aren’t listening to us.’ ”

I mentioned that one of his constituents had told me that she thought Sweeney had become too much of a big shot, and had lost touch with his district. “The woman you talked to,” Sweeney said, “she voted for me before but she really doesn’t know why she voted for Durr. I got too big for my britches? Really? In what way? They wouldn’t be able to describe it to you.”