Midway through his concurrence with the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down affirmative action, Justice Clarence Thomas deploys one of the most absurd and baffling arguments ever put to paper by a justice.

In order to argue that the Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend to authorize racially specific efforts to alleviate inequality, Thomas finds himself forced to explain the existence of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was reauthorized in 1866 by the same Congress that approved the Fourteenth Amendment. To square this circle, Thomas insists that the term freedmen was a “formally race-neutral category” and a “decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.”

The 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Act then expanded upon the prior year’s law, authorizing the Bureau to care for all loyal refugees and freedmen … Importantly, however, the Acts applied to freedmen (and refugees), a formally race-neutral category, not blacks writ large. And, because “not all blacks in the United States were former slaves,” “‘freedman’” was a decidedly underinclusive proxy for race.

If “freedmen” were a “formally race-neutral category,” then the Fourteenth Amendment does not authorize race-conscious efforts to remedy racial discrimination, and affirmative action cannot be constitutional. As an originalist, Thomas is supposed to interpret the Fourteenth Amendment as it was understood at the time it was written. He is attempting to reconcile his philosophy of judicial interpretation with what the history actually says; the other originalist justices do not really try, perhaps aware of the awkwardness of doing so. The problem, though, is that Thomas’s interpretation is obviously incorrect. His efforts at reconciliation ultimately illustrate the extent to which “originalism” is merely a process of exploiting history to justify conservative policy preferences, and not a neutral philosophical framework.

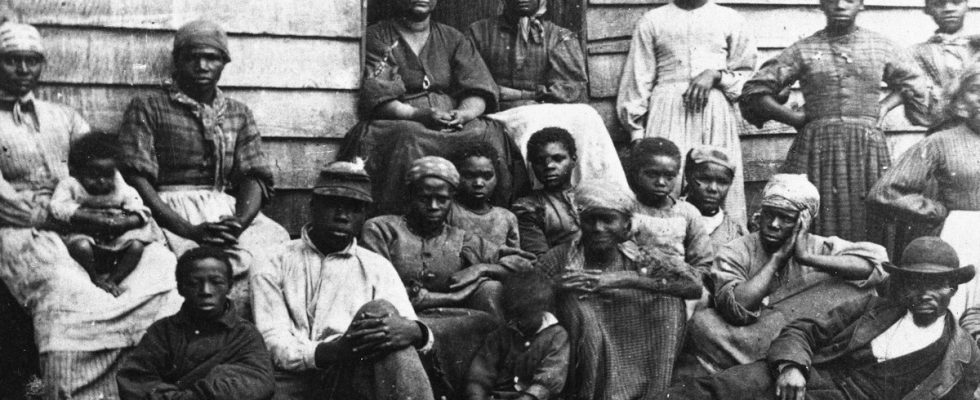

“Freedmen” cannot be a “formally race-neutral category,” because American slavery was not a formally race-neutral institution. Moreover, an extensive historical record illuminates the intentions of the lawmakers who passed the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts. They certainly did not see the term freedmen as racially neutral, and they intended the bureau to protect the rights of Black people in the South, whether formerly enslaved or not. We know this because they said so; the insistence to the contrary is the result of conservatives projecting their version of “color blindness” backwards through time.

“I don’t think Justice Thomas is correct—freedman was widely used as a synonym for Black,” Eric Foner, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Reconstruction, a historian cited in Thomas’s concurrence, told me in an email. “Ninety percent of Blacks were slaves in 1860, and everyone knew whom the Freedman’s Bureau Act was meant to assist.”

Republican lawmakers in the 1860s did not believe that targeting aid to Black people contradicted, as Thomas writes, a “commitment to equal rights for all citizens, regardless of the color of their skin.” They saw such racially conscious efforts as fulfilling that commitment. These lawmakers did not share modern liberal sensitivities either—contemporary perspectives on interracial marriage and integrated schools would have been foreign to nearly all of them, except perhaps Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner. Figuring out what the words they wrote meant at the time they wrote them requires understanding the very different dynamics of their era.

“The obvious problem is the mutually reinforcing relationship and considerable—if not complete—overlap between status and race at the time. The fact that not every Black person was recently freed didn’t make freedman a ‘race neutral’ term as used and understood during the 1860s,” Stephen West, a history professor at Catholic University, told me. “When Americans of the time talked about freedmen, they knew they were talking about Black people. And they knew that the association of Blackness with slavery marked the lives of Black people who hadn’t been recently enslaved.”

West was one of the historians who submitted a brief to the Court that exhaustively documents not only the extent to which Republican lawmakers saw their efforts as race-conscious, but the extent to which their Democratic opposition saw them the same way. As a Republican lawmaker put it during the debates over one of the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts, “The very object of the bill is to break down the discrimination between whites and blacks” and to provide for “the amelioration of the condition of the colored people.” One of the authors of the 1866 Freedman’s Bureau Act made clear that its aim was “to educate, improve, enlighten, and Christianize the negro; to make him an independent man; to teach him to think and to reason; to improve that principle which the great Author of all has implanted in every human breast.”

Its opponents, meanwhile, described it as “class legislation—legislation for a particular class of the blacks to the exclusion of all whites.” They complained, in rhetoric that has hardly changed in more than a century, that “hundreds and thousands of the negro race have been supported out of the Treasury of the United States, and you and I and the white people of this country are taxed to pay that expense.”

Thomas observes that “the Freedmen’s Bureau served newly freed slaves alongside white refugees.” But this distinction only emphasizes the fact that freedmen was not “underinclusive” of Black people, because the law conferred distinct benefits to “freedmen” that were not extended to “refugees,” including support for establishing educational institutions for Black children. Indeed, the full name of the bureau was the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, denoting a conscious distinction between the categories. As one Republican lawmaker cited in the brief put it, “We are interfering in behalf of the negro; let us interfere to educate him.” General O. O. Howard, the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, wrote in his memoir that “to these two classes, negroes and whites, were usually given the names of freedmen and refugees.”

Some of the bill’s supporters argued openly that the disparate treatment of the two groups was both deliberate and necessary. “The very discrimination it makes between ‘destitute and suffering’ negroes and destitute and suffering white paupers,” one Republican congressman asserted, “proceeds upon the distinction that, in the omitted case, civil rights and immunities are already sufficiently protected by the possession of political power, the absence of which in the case provided for necessitates governmental protection.”

As another of the legislation’s defenders argued:

We owe something to these freedmen, and this bill rightly administered, invaluable as it will be, will not balance the account. We have done nothing to them, as a race, but injury. They, as a people, have done nothing to us but good … We reduced the fathers to slavery, and the sons have periled life to keep us free. That is the way history will state the case. Now, then, we have struck off their chains. Shall we not help them to find homes? They have not had homes yet.

Included in the category of the “sons [who] have periled life to keep us free” were the many freeborn Black soldiers who defended the republic.

But look, you don’t have to take my word for it that freedmen was widely understood as a synonym for Black. You don’t have to take Foner’s or West’s word for it. You can take Clarence Thomas’s word for it, because in the 2022 Bruen decision, in which the Supreme Court struck down state restrictions on gun possession, Thomas uses the terms freedmen and blacks or negroes interchangeably.

For example, Thomas writes that “in the years before the 39th Congress proposed the Fourteenth Amendment, the Freedmen’s Bureau regularly kept it abreast of the dangers to blacks and Union men in the postbellum South.” Not “freedmen and Union men,” but “blacks and Union men.” Thomas uses blacks here in reference to those protected by the Freedmen’s Bureau, and distinguished from the more race-neutral Union men, precisely because he understood that it did not matter to the defeated Confederates what a Black man’s prior condition of servitude was. He does the same thing in another passage cited by the New Republic legal reporter Matt Ford. Here we have the glorious alchemy of originalism in full view, where the “original meaning” of the same words in an identical context changes depending on which policy is preferred by the originalist.

The authors of the Fourteenth Amendment were trying to undo a racially oppressive labor caste system, so they needed to focus on race. They would not have been trying to do so in a “race neutral” way, because they were not a party to 20th- and 21st-century conflict over the limited number of places in the factories of elite reproduction. The “originalism” that purports to examine the Reconstruction amendments as they were seen at the time replaces the perspective of their creators with the sensibilities of the contemporary conservative movement, in which virtually any form of discrimination can be justified by a veneer of color blindness while every means to pursue equality is constitutionally suspect. Thus a president can rant publicly about wanting to ban an entire religion from American shores and have his aims sanitized by white-shoe lawyers to the majority’s satisfaction, while race-conscious methods of fighting anti-Black discrimination are treated as the moral equivalent of a segregated water fountain.

This is not simply an inversion of the Fourteenth Amendment and the intent of the lawmakers who wrote it, but a replication of the arguments made by the opponents of its ratification. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, whose opinion is arguably more originalist in its reliance on the actual historical context of the era, observes as much in her dissent, noting that “nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment or its history supports the Court’s shocking proposition, which echoes arguments made by opponents of Reconstruction-era laws.”

The promise of originalism is that, by interpreting constitutional amendments as they were understood at the time, judges minimize the risk of lawless rulings that simply reflect their own preferences. In theory, originalism should not necessarily lead to a justice’s preferred outcome, preventing the law from being corrupted by personal bias. Perhaps you think affirmative action is immoral or bad policy; perhaps you think it largely benefits the most well-off minority students. Maybe you think the legal rationale of “diversity” used to defend it is strained. Maybe you agree with those who argue affirmative action is to blame for discrimination against Asian applicants, or that there are other, more class-oriented means to achieve affirmative action’s goals.

But the issue here is: Did the authors of the Fourteenth Amendment see efforts to help Black Americans as unconstitutional discrimination against white people? They very clearly didn’t. At the time, that was the position of the men who would have been just as happy if slavery had never been abolished at all.

The question is supposed to be what the Constitution allows, not what policies a justice prefers. As Thomas put it in a speech in 2019, “Words have meaning at the time they are written. When we read something that someone else has written, we give the words and phrases used by that person natural meaning in context.” To that he might have added, “Unless we don’t like the context.”

In 2014, the law professor Joel K. Goldstein observed that Thomas tends to rely less on originalism when judging race-related cases than “moral, consequentialist, and policy-oriented arguments that trigger his criticism—even outrage—in other contexts.” This might explain Thomas’s outburst at Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, dismissing her for seeking to “empower privileged elites.” Thomas is not used to invoking his—what’s the phrase? lived experience?—and having it challenged by someone with similar authority and a different perspective. Perhaps Thomas can discuss the malign influence of privileged elites on Supreme Court justices on his next fully paid vacation with the conservative billionaire Harlan Crow.

The Fourteenth Amendment authorized race-conscious remedies for discrimination against Black people. The people who wrote the amendment understood it that way. The people who opposed the amendment understood it that way. But that is not the outcome Thomas or the Court’s other originalists wanted, so they waved it away as irrelevant.

In a recent ruling striking down a prohibition on gun possession for convicted felons, the federal judge Carlton Reeves wrote that the Supreme Court’s precedents, in particular Thomas’s Bruen opinion, bound him to a certain conclusion, which is that nearly all firearm restrictions are unconstitutional. Nevertheless, Reeves lamented originalism’s focus on interpreting history, because “it is not clear that founding‐era Americans collectively agreed that for time immemorial, their descendants would be bound by the founding generation’s views on how the Constitution should be read.” The authors of the Fourteenth Amendment may have intended the opposite of that.

But let’s not fool ourselves. The purpose of originalism as the right-wing justices practice it is to provide a basis for ruling in favor of conservative policy outcomes that borrows the moral authority of those they see as the protagonists of American history. The history itself doesn’t matter. If it did, we wouldn’t be here.