Everyone’s family history is complicated. Nearly everyone has an estranged sibling, a drunken uncle, a contentious aunt, or a well-kept secret trauma. With DNA testing and genealogy websites, everyone is almost guaranteed to find a cousin, a half-sibling, or even a parent previously unknown to them. During American slavery, the bloodlines of slaveholding families were particularly fraught. Without technology, “Mama’s baby and Papa’s maybe,” as the saying goes, could be kept hidden. When an enslaved child had red hair, freckles, and the same dimple or gait as their biological father, everyone noticed, but they never discussed these relationships. Behind the family portraits, genetics told everything. The irony among slaveholders and their enslaved descendants was that light skin meant little. Slavery did not discriminate: The children of white masters could be bought, sold, beaten, or sexually assaulted. Interracial relationships did not bring people together in an era of slavery; rather, they kept them apart.

The family history of the Grimkes features many of these complications. In a single family tree, there were generations of slaveholders, enslaved people, abolitionists, and free-born Black descendants. There was wealth and poverty, inherited money and self-made men. The Grimke family tree encompassed the spectrum of bondage and freedom. In The Grimkes, the historian Kerri Greenidge offers a powerful and unique account of this family’s history—an account that offers tales of slavery, violence, loss, resilience, and redemption.

Greenidge is an exceptional storyteller. She, too, hails from a family of thinkers and writers who have used their genius to create and foster new conversations regarding old problems or marginalized people. In her previous book, Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter, Greenidge explored the challenges of the civil rights milieu with a long-overdue biography of one of the most popular yet understudied Black voices of the early 20th century. William Monroe Trotter was an editor for the Guardian, the Boston-based Black newspaper, and a longtime political agitator. With her new book, Greenidge returns to New England as well as to the Grimkes’ hometown of Charleston, S.C. Her story is one about race, region, class, and belonging—within a family unit as well as in one’s country—but it is also about the circuits of abolitionist activism and Black political rights that spread from the South to the North and vice versa. Spanning more than 200 years, The Grimkes offers a history of slavery and elitism, activism and apathy, complicity and courage, that is comparable to Annette Gordon-Reed’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. It offers a glimpse into all the inner workings of interracial families grappling with slavery, sexual assault, and racial divisions. It also offers a story of the Black Grimkes, trapped by their link to one of the more famous surnames in the North and the South and feeling the pressure to live up to the family’s exceedingly high standards.

Perhaps the most famous of the Grimkes were the celebrated sisters Sarah Moore Grimke, born in 1792, and Angelina Emily Grimke, born in 1805, who grew up in one of the largest slaveholding families in Charleston. Their father, Judge John Faucheraud Grimke, had 14 children and owned hundreds of enslaved people, which made him extraordinarily wealthy. Judge Grimke believed in the institution of slavery and in the use of violence to maintain it. Brute force was the Grimke way, and it was passed down to his sons, who beat and whipped their enslaved human property, even those who shared a bloodline with them.

Sarah Grimke expressed at an early age her abhorrence of slavery. As an adult, she persuaded Angelina to leave the South with her, and the pair moved to Philadelphia and then to Boston, where they fought for the end of slavery and for women’s rights. The Grimke sisters were often praised for abandoning the family business; they gave public lectures and wrote antislavery essays. Angelina married the abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld and had her writings published to acclaim in William Lloyd Garrison’s leading antislavery newspaper, The Liberator. Most notably, Angelina wrote “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” imploring Southern women to petition their state legislatures and church officials to abolish slavery. Together, Sarah, Angelina, and Theodore penned American Slavery as It Is in 1839, which became a bestseller in abolitionist circles.

The Grimke sisters were opposed to slavery, but as was the case with some white abolitionists, Greenidge notes, their cause “rarely included a recognition of the lives of the enslaved…. Black people themselves were mere objects within the constellation of sin that surrounded [them].” In this way and others, the Grimke sisters were confounding. They were outspoken regarding abolitionism and women’s rights. They took to the lecture circuit, railing against the injustices of slavery and, to some extent, patriarchy. But they also did not see Black people as equals, even if they saw slavery as an abomination, and they were not always willing to confront the violence inflicted on their Black neighbors. Greenidge opens her book with the horrific story of a white mob attacking Black people in Philadelphia in 1834. During the riot, Black homes and businesses were destroyed and Black churches were reduced to rubble. For three consecutive days, more than 600 white men terrorized the city’s Black residents. No one was spared, neither the young nor the old. A Black man named Daniel Williamson, believed to be a former slave of George Washington, was dragged from his home and kicked mercilessly. He was 95 years old. This was not the first time Philadelphia had exploded in violence against Black communities. In 1820 and 1829, and again in 1835, 1838, 1842, and 1849, anti-Black and anti-abolitionist mob attacks and campaigns of violence turned the city into a ticking time bomb for Black residents. Yet during the 1834 riot, the Grimke sisters said not a single word in recognition of the racial violence that destroyed Black life in their city. Nor did the sisters ever fully confront their own complicity in their family’s slaveholding. They never discussed their own role as slaveholders or attempted to center the voices of the enslaved. Although they didn’t intervene when the violence was taking place, they certainly could have. Their refusal to acknowledge and make amends for their actions—or lack thereof—was not a hypocrisy limited to themselves. Many white liberals, then and now, have bleeding hearts and blind spots.

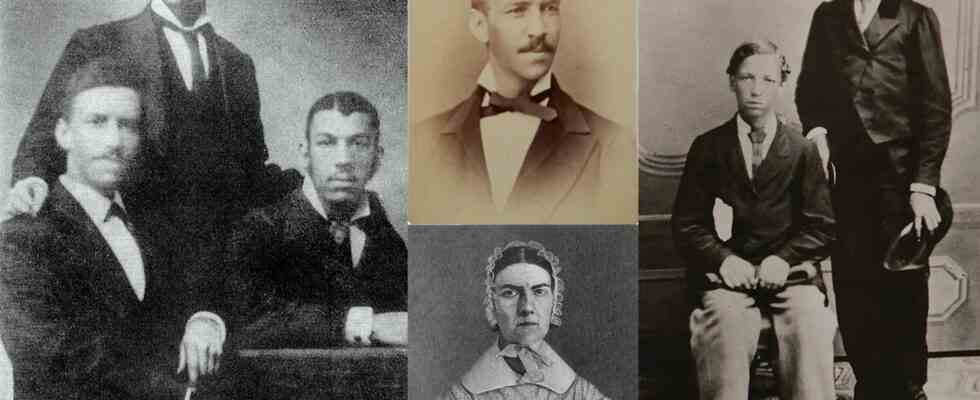

Greenidge spends large portions of the book revealing the inner lives of the Black Grimkes and their relationships with their white relatives, including the sisters. Back in South Carolina, Sarah and Angelina’s brother, Henry Grimke, was a prominent slaveholder and lawyer. When his white wife died, Henry took on Nancy Weston, a mixed-race enslaved woman, to serve as his common-law “wife” and fathered three children, Archibald, Francis, and John, with her. Though he promised to free them all and could have done so legally, Henry never did. On his deathbed, he willed Nancy and their three sons to his oldest white son, E. Montague Grimke. “Montague was a brute,” according to Archibald. He beat his half-brothers relentlessly as children and as teenagers. Only after the Civil War ended did the Black Grimke brothers secure their freedom. All three were sent to be educated at the HBCU Lincoln University. When Sarah and Angelina realized that their brother had Black children, they made efforts to locate them and help them gain a footing in life. But they also never let them forget it. The sisters charged their nephews with being selfish, greedy, and lazy, even though Archibald and Francis earned graduate degrees from top schools and became successful—indeed, part of the country’s Black elite—despite their past enslavement. Their lives were nothing short of remarkable.

Archibald achieved perhaps the greatest prominence among the brothers. He graduated from Harvard Law, worked as an attorney, and later became the American consul to Santo Domingo. He took on a leadership role in the NAACP and was very much the “race man” society expected him to be. He would also impose his high standards of excellence on his only child, which strained and at times contaminated their relationship.

For his part, Francis was educated at Princeton Theological Seminary and led the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, the largest Black church in Washington, D.C., and he was also active in helping to establish the NAACP. He married Charlotte Forten, the granddaughter of the wealthy Black Philadelphia sailmaker and abolitionist James Forten. Charlotte was a third-generation abolitionist and very accomplished in her own right: She spoke several languages and was the first Black woman to graduate from Salem State Normal School in Massachusetts. During the Civil War, she became good friends with Robert Gould Shaw, the leader of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and served as a nurse tending to the wounds of Black soldiers. After the war, she traveled to the South Carolina Sea Islands to teach formerly enslaved people. Charlotte and Francis had one child, but she did not survive past infancy.

Born into slavery before becoming self-made men, the two older Black Grimke brothers mistakenly believed that their free status, family name, education, and even their fair skin would shield them from the harshness of white supremacy. But as Greenidge shows, they eventually became disillusioned with the Republican Party, and they also attempted—unsuccessfully—to fight segregation among the holders of federal office under a Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson. They also failed to garner support to combat racial discrimination against Black soldiers. For all of their success, neither brother could fully return to the South, either. They learned that successful Black leaders became the targets of white supremacist violence, such as the Wilmington Massacre or the murder of Frazier Baker, a federally appointed postmaster in Lake City, S.C.

Greenidge also details the pressures they felt in upholding the family’s name and its reputation for achievement. Archibald’s only child, Angelina Weld Grimke (known as “Nana” to her family and friends), was plagued by the public scrutiny and her father’s demands to be exceptional. Her family prevented her from doing anything deemed unworthy of her status and class. Marriage became all but impossible, particularly as Angelina showed affection for other women. As an adult, she chose never to marry or have children. She poured much of her passion into her writing, including her well-known play Rachel, one of the first plays written by a Black woman, which discusses such themes as racism, depression, and the horrors of lynching. Angelina had a brief moment to shine during the Harlem Renaissance, but for the majority of her life she could not find happiness. She never fully understood—and yet still carried—the ghosts created by the hardships that her father and uncles had suffered during slavery. “The past is the past,” Archibald once told her. “Haven’t I give you a life of perfect harmony for which the past is no longer relevant?” But for Angelina, the past was always relevant. She wanted to know how her father and uncles had managed a life that was born out of rape and enslavement. How did they navigate their traumas, their losses, and even their successes? Nana could not reconcile herself to the fact that despite all of their striving and achievement, the Black Grimkes had not yet attained freedom—which is to say, true liberation.

Family histories can be unsatisfying, because they can sometimes leave readers with more questions than answers. For older generations, the past was often something no one wanted to relive; shame and stigma held people hostage to their grief. Moreover, writing a family history like The Grimkes can be difficult. For starters, there are the many shared names among both women and men; there are the nicknames used by all and the first names that go virtually unmentioned outside of official documents. But Greenidge is masterful at keeping all of the various Grimkes’ narratives intact and accessible. It is impossible to mistake a Black Grimke for a white one in her book—the demands on their lives were utterly different. What is significant and even powerful about the Grimkes’ story are the questions it raises about how to facilitate the healing of racial trauma. Every member of the family needed to grapple with the harm they caused or endured and the limitations placed on them. Greenidge doesn’t have all the answers, but she shows us what will not work, and that example is just as useful as knowing what will.

Ranging over centuries of American history, The Grimkes is both timely and sadly timeless. Greenidge argues brilliantly that her book is a story of “the limits of interracial alliances when it comes to the eradication of deeply entrenched white supremacist violence and policy.” As a country, we have not managed to join forces along racial and economic lines to create lasting, structural progressive change for those who need it the most. Money, success, and respectability cannot heal the wounds of racial trauma. Greenidge’s book is almost a cautionary tale: The Grimke sisters and their white descendants were still trapped by their racial myopia and cognitive dissonance as it related to their family and the world they wanted to shape. With many white abolitionists, emancipation was the sole and ultimate goal. But abolition was not enough, because as many Black people understood, emancipation was just the beginning of equality, citizenship, and reparations, not the end.

Francis Grimke once said, “Race prejudice can’t be talked down, it must be lived down.” I agree. I might also add that activism is not hereditary. Each generation must be raised to understand that care and progress have to benefit everyone. There needs to be a constant reminder, because families and society at large would rather forget. Greenidge’s rich historical text, with its thoroughly researched genealogy, reads like a novel, offering us, for the first time, a deep yet wide-ranging portrait of this complicated family, in black and white. The Grimkes is family history at its finest. In many ways, it represents the story of America itself: the good, the bad, and the forgotten.