Latinos and their ancestors have lived in the Americas for 500 years, yet it feels like many Americans are perpetually in the act of discovering us—especially when elections are looming. We are instrumental to the emerging Democratic majority that Blue America longs for, that Red America fears, and that never quite seems to arrive.

The 2020 census showed that Latinos accounted for more than half of the country’s population growth over the previous decade; as a matter of math, we are indeed a large part of the country’s future. What this means for the country’s politics is less clear.

The conventional wisdom that Latinos are reliable members of a liberal coalition of people of color has never been exactly right: Between a quarter and a third of Latinos have voted Republican in almost every presidential election for the past half century. Donald Trump grew his share of the Latino vote in 2020 compared with 2016, and he may be growing his share still. A November Wall Street Journal poll found that Hispanic voters would be evenly split if Trump ran against Joe Biden in 2024. They were also evenly split when asked whether they would vote for Democrats or Republicans if the midterm elections were held that day. The survey pool was admittedly a small one, but the possibility of a continued rightward shift is shaking Democrats’ confidence.

How, I am often asked, can so many Latinos be willing to vote for Trump or his acolytes after he spent four years in office maligning them?

In some ways, it’s an insulting question, because it presumes that non-Latinos know our interests better than we do. I didn’t support Trump, but my grandfather did. For a long time, Latinos like him have gravitated toward the Republican Party because of their belief in free-market capitalism, their opposition to big government, and their religious and cultural conservatism. Many appreciated the booming economy of the Trump years, and worry about inflation today. It’s ridiculous to imagine that Latinos would all think, or vote, the same. There are more than 60 million of us—representatives of different national groups, with different accents, histories of migration, and cultural tastes. Has such a varied group ever formed a solid bloc?

But America’s inability to wrap its head around a fifth of its population suggests a deeper misunderstanding. It has to do with an ignorance of Latino history—a messy history of colonization that is far more important to grasping our political diversity than any poll result could ever be.

Too few Americans learn this history, in part because Latinos are rarely central to the ideological debates over race and racial justice in America. Or, more precisely, we are props in those debates, our story reduced to a simple tale of oppression consisting of the violent erasure of our Indigenous heritage, resistance against colonialism, and victimization by imperial powers. In this view, only Latinos who are unconscious of their own inheritance would fail to align themselves with the left. As Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York put it in an interview, Latino politicians often advance “really problematic policies” because they don’t “know who they are.”

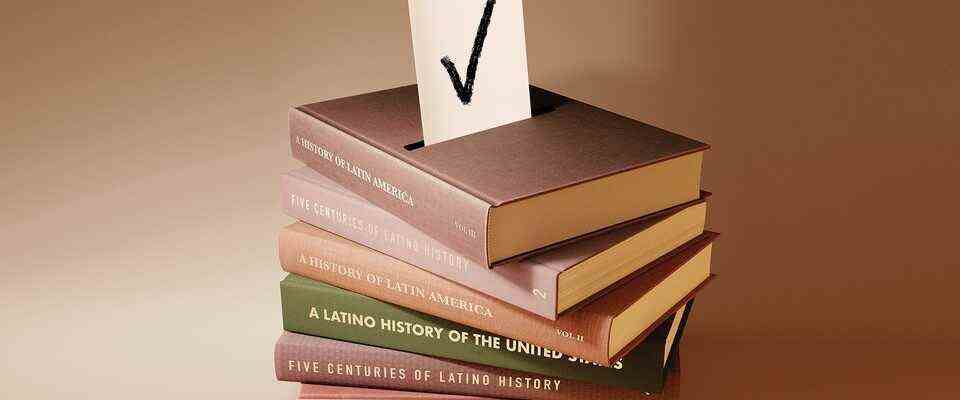

But who we are is complicated, and the future that many Latinos imagine—for ourselves and for our country—does not fit neatly into the prevailing culture war. To understand that, it may be helpful to pause the angst over which box Latinos will check on their ballots this year or in 2024, and consider what can be learned from the past.

Throughout history, Latinos have been both colonized and colonizers. By this, I don’t mean simply the obvious: that Latinos are mestizos, the mixed-race descendants of Indigenous Americans, Spaniards, Middle Easterners, Africans, and other ethnic and racial groups. I also mean that Latinos have identified not only as survivors of imperialism and its ills, but also as supporters of imperial and national powers. As the historian Serge Gruzinski put it in The Mestizo Mind, the different groups that came together to forge Latino identity were like “prisoners in a maze,” bound to one another by the pain of conquest and the imperative to build new societies from the ashes.

That pain, of course, was extraordinary. The spread of the Spanish and American empires was achieved through great violence against African and Indigenous people and their mixed-race descendants. They were slaughtered, enslaved, and raped, their cultures and religions destroyed. These are necessary and hard truths, and they became more widely acknowledged in the mid-20th century, when decolonization movements swept the world and more people began speaking out against the legacies of white supremacy.

When that happened, more Latinos began to identify with their Indigenous and African roots, in opposition to the old imperial powers. Some called for an Indigenous revival: Puerto Ricans claimed Taíno identity, and the Young Lords, an activist group fashioned after the Black Panthers, fought for Puerto Rican independence. Chicanos referred to the Southwest as Aztlán, the mythical homeland of the Aztecs. In 1972, Rodolfo Acuña published his influential history Occupied America, which argued that Mexican Americans were internally colonized subjects of the United States.

Activists in the U.S. saw their histories and futures as linked to those of other colonized populations. They founded advocacy groups, ran for office, and argued that people of color should work together to build power. They have since shaped how Latinos are portrayed in the news and in popular culture.

As Latinos themselves, they are unimpeachable experts on Latino identity. But the punditocracy of Democratic politicians, strategists, and consultants has painted an incomplete picture of Latino history. Many Americans have ceded to them the representation of all Latinos, instead of seeking out more complex narratives.

They seem to have forgotten—or don’t want to remember—that in the centuries since the initial collision of Europe and the New World, many Latinos have chosen to align themselves with the imperial and national projects of Spain, the United States, or the independent nations of Latin America. Across the 19th century, many Latin Americans viewed the United States as the economic and political model for their own countries, seeking alliances with, and maybe even annexation by, the northern colossus.

In the 1830s, Mexicans fought on both sides of the Texas Revolution. After the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, when the United States took half of Mexico’s land, the overwhelming majority of Mexicans who lived in the former Mexican territory chose to stay and become U.S. citizens. In a bizarre episode from the 1850s, during a power struggle in Nicaragua, one faction invited the American mercenary William Walker to come “civilize” their country. He rigged the vote and got himself elected president for almost a year, until his supporters soured on him.

At the close of the century, after Puerto Rico and Cuba won their independence from Spain, some wanted the United States to remain involved in the governance of the islands, even if that meant freedom from one empire through absorption by another. A contingent of prominent Puerto Ricans tried, and are still trying, to convince the United States and fellow islanders that Puerto Rico should become a state. (In a 2020 referendum, just over half of Puerto Ricans said they supported statehood.)

Latinos who cast their lot with the United States had their reasons—economic, political, and cultural. Many felt that Spain was tradition-bound and backwards-looking, while the U.S., a modern liberal democracy, represented progress. Some established businesses that relied on U.S. investment, sent their children to school in the North, treasured its social and religious liberties, and converted from Catholicism to evangelicalism. It is certainly the case that many of those seeking inclusion have been excluded from full citizenship or stymied by racism. But that experience hasn’t always shaken their faith that the United States stands for opportunity and prosperity, nor has it blunted their patriotism.

The French West Indian philosopher Frantz Fanon, in 1952’s Black Skin, White Masks, argued that colonized people identify with their colonizers—wanting to walk, talk, and dress like them, and to have sex with them—because of a colonial “inferiority complex.” His views are echoed by many liberal Latinos today, who consider their more conservative counterparts sellouts, as if they are somehow not “real” Latinos.

Watch YouTube videos of people revealing the results of their DNA tests, and the discomfort can be palpable. An Afro-Latina in one was taken aback because she “wanted to be more Black,” and “didn’t want to be a part of colonization.” A man in another was “trippin’,” he said, because he’d learned that he was 31 percent Spanish. On a podcast, the journalist Maria Hinojosa said she had to “come to terms with the fact that I have conquistador blood in me,” but that she deliberately identifies more with her Indigenous heritage.

Many Latinos prefer to identify with a particular thread of their ancestry as a way of connecting with a culture that they feel was stolen from them, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But no one thread tells the whole story. A contemporary of Fanon’s, the French Tunisian writer Albert Memmi, argued that the colonizer and the colonized are inextricably tied to each other and can even inhabit the same body. They define their struggles and desires in relation to each other. To be connected in this way has a psychological cost, but it is also a fact.

When it comes to Latino history, I find Memmi’s take more useful than Fanon’s. I have always been curious about my identity as a Latino. My dad’s family is Mexican, Colombian, Panamanian, and Filipino. My mom’s family is white, from Germany, Scotland, and England. They lived across the street from each other in the borderlands of Tucson, Arizona, in the 1970s, when both of my grandfathers were stationed at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

My parents got divorced, and much of my childhood was divided between these two families. I was educated in the predominantly white communities of Irvine, California, and then Princeton, New Jersey, where my father worked as an English professor. Summers and breaks I spent in Tucson, where my mom’s brother called me “green bean,” because I was half gringo and half “beaner.” My paternal grandparents spoke to me in Spanish, but I began studying the language formally only when I was in middle school. My father schooled me more in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walter Benjamin than in those of Octavio Paz, Gloria Anzaldúa, or Sandra Cisneros.

In college and grad school, I tried to make up for what I had missed, and worked toward becoming a scholar of Latino history. It’s possible that all of the reading and writing I’ve done since has been an effort to understand both sides of my identity, and how my experience fits within the broader patterns of that history. If you’re wondering whether my argument about Latinos as both colonizers and colonized is the result of my own identification with both, you’re right. How could it be otherwise?

A design change in the latest census allowed people to more easily identify themselves as mixed-race. This helps explain why the percentage of Hispanics who said they were of two or more races instead of, for example, only white or only Black increased dramatically—by 576 percent. At the same time, demographic and cultural shifts have meant that there are both more mixed-race Americans and more Americans who understand themselves as mixed-race. Those who believe that race is a pernicious and artificial construct should welcome the ways in which Latinos are embracing more complicated narratives of themselves and their country.

Americans of all races are engaging in debates about our national origins because we sense that something is broken. I admire how the 1619 Project, from The New York Times, challenged us to reconsider U.S. history, with slavery and its afterlives as the cornerstone. One problem with the project, though, and with the Trump administration’s answering 1776 Commission, is that the framing of each reinforces a Black-versus-white vision of American history. Addressing the legacy of slavery is vital. But adding Latino history (itself, in part, a history of slavery) to the story of American origins would help us think in brown, the color of “impurity,” as the writer Richard Rodriguez described it some 20 years ago.

America has always been many things at once. If we limit our understanding of the nation’s beginnings to the British colonies, then how could Latinos and members of other groups be anything besides outsiders and latecomers who should be compelled to assimilate? The slogan “America is a nation of immigrants” is supposed to make us feel included. But we are all original Americans, and we all shaped the United States before there was a United States.

By recounting this long history, I am not trying to suggest what Latinos should believe. I am only saying that when we vote, we aren’t just casting ballots about health care or education policy. We are expressing political identities that have evolved over centuries—for and against expanding empires and nation-states; for and against more radical forms of egalitarianism—in ways that don’t always fit neatly into the rhetoric of the left-right divide.

This is why many Latinos support tougher border controls to limit the influx of undocumented immigrants, whom they may see as threatening their own privileges or sense of belonging as U.S. citizens. It is why many find the Republican Party’s emphasis on love of country so appealing.

Understanding this history won’t allow anyone to predict “the Latino vote” with pinpoint accuracy. But it would at least help free us from the myth that Americans vote according to ahistorical ideas of inherited guilt or innocence. And it should remind us that we are in some way bound to one another—that for better or worse, what it means to be Latino and what it means to be American are intertwined.

This article appears in the March 2022 print edition. When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.