Society

/

January 23, 2024

Israel is trying to snuff out journalism in Gaza. This should be a sound-the-alarm, all-hands-on-deck moment for anyone who professes to support reporters and the work that they do.

Families, loved ones, and colleagues attend the funeral ceremony of two journalists—including Hamza Dahduh, the son of Al Jazeera correspondent Wael Dahduh—in Rafah, Gaza on January 7, 2024.

(Stringer / Anadolu via Getty Images)

It was a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it line, deep into a gauzy New York Times puff piece published on Friday about women fighting for the Israeli military in Gaza. In between lauding female soldiers striking a blow for gender equality while helping carry out a war that has overwhelmingly killed women and children, the paper’s longtime Jerusalem correspondent Isabel Kershner made this brief aside (emphasis mine): “The Times accepted a military transport to secure rare access to wartime Gaza, which is typically off-limits to journalists. The Times did not allow the Israeli military to screen its coverage before publication.”

The implication here is that Gaza is a journalistic black hole, an opaque and mysterious land that reporters are cut off from. And it is true that journalists from outside Gaza have been allowed inside only on the back of Israeli tanks. But Kershner’s sweeping statement erases the many Palestinian journalists inside Gaza who have been working under brutal circumstances for the past three months. More offensively, it erases the Palestinian journalists inside Gaza who have been killed at a rate unlike anything the world has seen in living memory. And the Times isn’t alone in doing this. The entire US media establishment has paid scant attention to what appears to be a deliberate attempt to kill all Palestinian journalists in Gaza.

If there’s one thing that journalists like to pride themselves on, it is their solidarity with other journalists. In theory, this solidarity is based on principles that transcend political and national boundaries. In 2009, for instance, White House correspondents revolted en masse after the Obama administration attempted to ice out Fox News on the (accurate) grounds that it was a conservative propaganda network; Obama was even questioned about the controversy in an NBC interview. In 2013, the detention of three Al Jazeera journalists by the Egyptian government prompted worldwide outrage. Russia’s continued jailing of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich has similarly become an international cause célèbre. Journalists in the Philippines and Russia were given the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021. In 2022, the Pulitzer Prizes awarded a special citation to the journalists of Ukraine for their “courage, endurance, and commitment to truthful reporting during Vladimir Putin’s ruthless invasion of their country.”

The list goes on, but the idea is the same: that journalists everywhere, no matter their affiliations or backgrounds, have a right to do their work without fear of repression, government censorship, or, worst of all, death.

Journalists are specifically protected in international humanitarian law, and their deaths are frequently described as having occurred “in the line of duty,” language that echoes the way we talk about soldiers. Journalists who die are often referred to as martyrs—people who gave their lives for a noble cause. Their killing is typically seen as a particularly grave violation of human rights and is given extra prominence in the media. The murdered Saudi Arabian journalist Jamaal Khashoggi, for instance, was named a Time Person of the Year.

Current Issue

So you would think that what has happened to journalists in Gaza would be treated with similar horror and given similar prominence—especially because it is so much worse than anything the journalist community has grappled with in generations.

The Israeli military has killed at least 76 Palestinian journalists since October 7, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Local Palestinian groups put that figure much higher, at over 100. The International Federation of Journalists estimates that there were around 1,000 journalists working in Gaza before October 7. That would mean that between 7.5 and 10 percent of all the journalists in Gaza have been killed since then. By comparison, an estimated 1 percent of Gaza’s population as a whole has been killed—meaning that journalists are one of the most disproportionately affected groups in an already blood-soaked region.

Even if we accept the lower figure, that’s still more journalists than were killed in 10 years of the Vietnam War. It’s more than were killed during all of World War II. It’s more than four times the number of journalists who have been killed covering the war between Ukraine and Russia. The CPJ says that more journalists were killed in Gaza during the first 10 weeks of Israeli bombardment than “have ever been killed in a single country over an entire year.” The speed at which so many journalists have been killed is something we have never experienced in modern history.

Moreover, this level of killing by Israel—a country with a history of targeting Palestinian journalists and news outlets—appears to be intentional. In October, the Israeli military told Reuters and Agence France-Presse, two of the world’s most venerable news organizations, that it could not guarantee their reporters’ safety in Gaza. Israeli politicians, including the defense minister, have publicly called for journalists to be killed. The military has blocked access to medical care for injured journalists who later died. And this pattern is not confined to Gaza—for instance, an investigation by Reporters Without Borders concluded that Israel had deliberately assassinated Reuters journalist Issam Abdallah in Lebanon in October; Abdallah was reportedly wearing a press vest and was not near the site of any fighting at the time of his killing.

Multiple journalists—including two who have written for The Nation in recent months, Youmna El Sayed and Mohammed R. Mhawish—have reported being personally threatened by Israel. (An Israeli air strike hit Mhawish along with his entire family while they were sleeping; miraculously, everyone survived.) The CPJ wrote in December that it had identified a pattern of this kind of behavior by Israel.

Most infamously, Israel has repeatedly targeted Wael Dahdouh, Al Jazeera’s Gaza bureau chief, killing his wife, two of his sons, his daughter, his grandson, and his colleague in a string of air strikes; Dahdou was injured in one of those strikes, and has now been transported to Qatar for medical treatment.

Taken together, it’s clear that journalism itself is being snuffed out in Gaza, the center of one of the most important stories on the planet. This is red-alert, sound-the-alarm, all-hands-on-deck moment for anyone who professes to support the ability of reporters to carry out their work.

Why, then, is the plight of Gaza’s journalists such an afterthought—so unimportant to the US media that, months into the war on Gaza, The New York Times is overlooking them as casually as Kershner did? Why, when I scrolled back to the very beginning of the Times’ landing page for its coverage of the Israel-Gaza conflict, could I find a few stories about the killing of individual journalists in Gaza but no news articles that took a comprehensive step back to give readers a sense of the scale of the death toll and the effect that such an assault on journalism might have on the way the world understands this conflict? (The Times did run an op-ed by reporter Lama al-Arian back when the reported journalistic death toll in Gaza stood at 60.)

Here’s another statistic. I checked the transcripts of every single edition of four Sunday morning talk shows—NBC’s Meet the Press, ABC’s This Week, CBS’s Face the Nation, and CNN’s State of the Union—between October 8 and January 14. I did this because these shows are typically seen as the most prestigious, serious, high-profile public affairs content on television. They are also the most reliable places to find interviews with powerful public officials.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In the last three months, a long list of US and Israeli government figures—including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israeli Ambassador to the US Michael Herzog, Israeli President Isaac Herzog, US national security adviser Jake Sullivan, and more—have spoken to these shows, sometimes multiple times. Across all of these interviews, on all of these networks, with all of these different people, over all of this time, I found exactly one question about the killing of journalists in Gaza, from Jake Tapper to Blinken on December 10. (Blinken did not directly answer the question about how he can explain why so many journalists were being killed and said only that the deaths should be “investigated”; Tapper did not follow up.)

I could have missed something, but it’s obvious that, on the whole, this issue is not a priority for the US media establishment. There have been no major press freedom campaigns from US journalists in defense of Palestinian reporters that I can think of; it has been left to groups like Writers Against the War on Gaza and elected officials like Rashida Tlaib to hold vigils in their memory. The Society of Professional Journalists, often described as the oldest and largest journalists’ association in America, prominently features statistics about the killing of journalists in Ukraine on its homepage, and has set up a special fund to help Ukrainian reporters. There are no similar initiatives on its website about journalists in Gaza as of this writing.

Some might ask why the killing of journalists deserves outsize media coverage compared to the killing of ordinary Palestinians in Gaza. The media industry tends toward navel-gazing, and the focus on journalists—who are often more educated, well-connected, and unrepresentative of the broader population—can sometimes blot out the stories of everyday people.

But the elite US media isn’t particularly interested in the lives, or deaths, of anyone in Gaza, whether they are journalists or not. And this isn’t just any old media story. The people reporting from Gaza are not White House correspondents sitting snugly in a briefing room. They are some of our only reliable sources of information about one of the most devastating and politically consequential humanitarian crises of our time, and they have shown a dedication to their work that renders words like “heroic” hollow at best. For this, they are paying a price unlike any group of journalists in the modern history of journalism.

So the question remains: In a news industry that usually does purport to treat journalism with such reverence, why are journalists in Gaza not being uplifted and defended more often? Or, put another way: If a government that was not Israel were carrying out an unprecedented massacre of journalists who were not Palestinian, would our media establishment care more?

-

Submit a correction

-

Reprints & permissions

More from The Nation

It may seem like there’s little to cheer, but these leaders and activists can show us how to keep fighting the good fight in what promises to be a challenging 2024.

Feature

/

John Nichols

A new podcast takes us back to the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis, when a mystery virus began spreading among New York’s Black and brown communities.

Editorial

/

Lizzy Ratner

Liberals are in denial. Conservatives are trying to destroy public health. And the virus is still raging.

Comment

/

Gregg Gonsalves

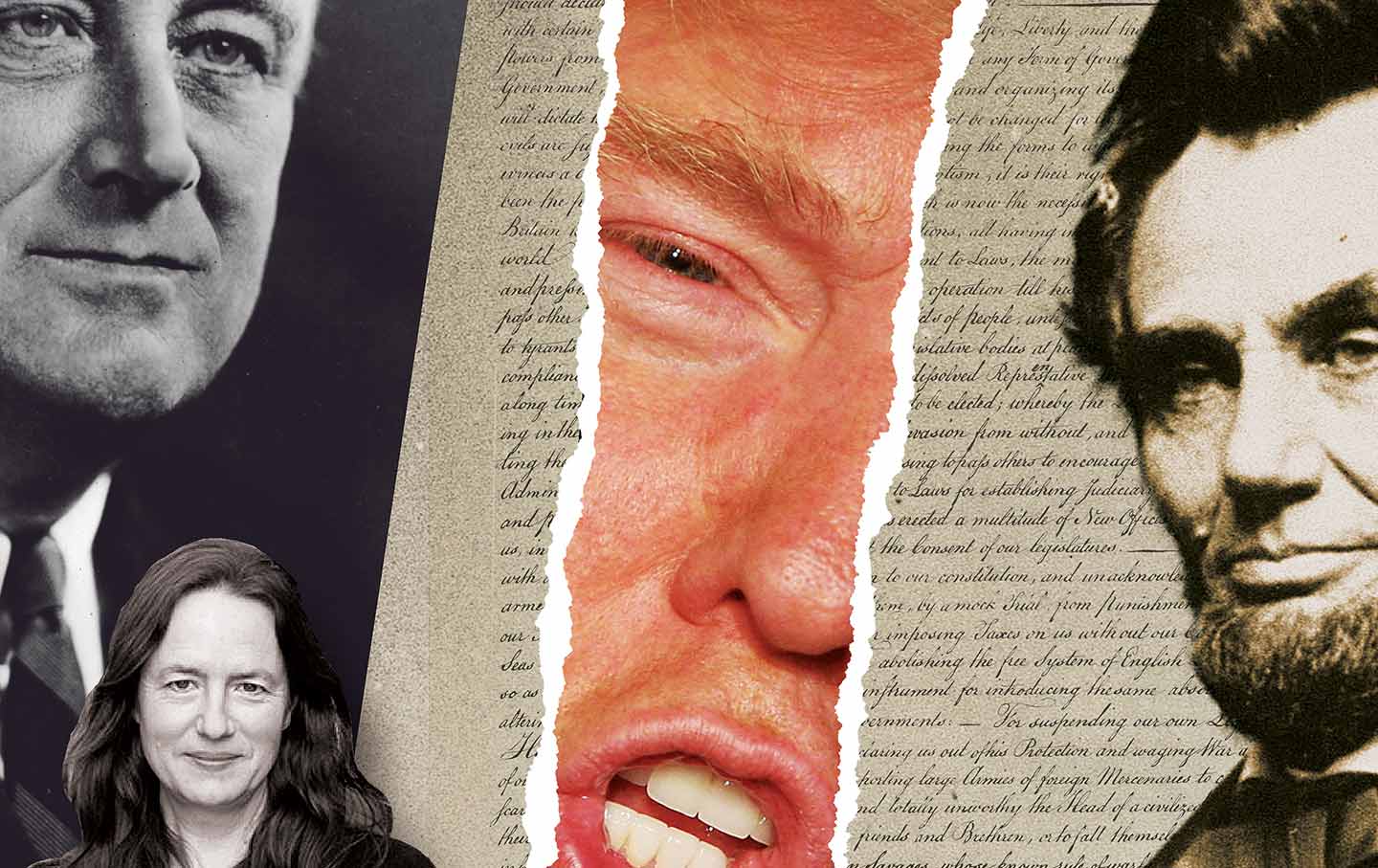

One interpretation presents the country as irredeemably tainted by its past. Another contends that the United States has also tended toward egalitarianism.

Books & the Arts

/

Kim Phillips-Fein

We all have doppelgängers, and we now know Colin Kaepernick’s is Aaron Rodgers.

Dave Zirin

Long before the Sacklers appeared on the scene, families like the Astors, the Peabodys, and the Delanos cemented their upper-crust status through the global trade in opium.

Feature

/

Amitav Ghosh