“A poem is never finished,” wrote Paul Valéry. “[I]t is only an accident that puts a stop to it—i.e., gives it to the public.” Sometimes that accident is death, but, as Valéry himself knew, having left behind some 28,000 pages of notebooks when he died in 1945, there are many ways for a poet to be posthumous, just as there is more than one way for a poem to go unfinished. One can be almost entirely posthumous like Emily Dickinson, who published only 10 poems in her lifetime, or like Isidore Ducasse, whose career as the Comte de Lautréamont, author of Les Chants de Maldoror, which had been read by only a handful of people, was cut short at the age of 24 during the Siege of Paris. One can be partially posthumous like Fernando Pessoa and Robert Walser, whose unpublished writings, discovered in a trunk and a few shoeboxes after their respective deaths, were major enough to occasion significant reevaluations of their literary output.

Or, less dramatically, one can be incidentally posthumous like John Ashbery, a poet as renowned in our day as Valéry was in his, whose publication record did not ebb even as he approached his 90th birthday, and whose unfinished work, stored in more or less well-organized files in his homes in Hudson, N.Y., and Manhattan, simply represents what he did not consider ready to undergo the accident of being handed to the public during his lifetime. Despite the aura that is surreptitiously injected into the term, “posthumous” is a designation for publishers and readers, not for writers. Poems, it ought to go without saying, are always written during specific points in a writer’s life, even if readers sometimes receive them, to quote the final line of Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” as “whispers out of time.”

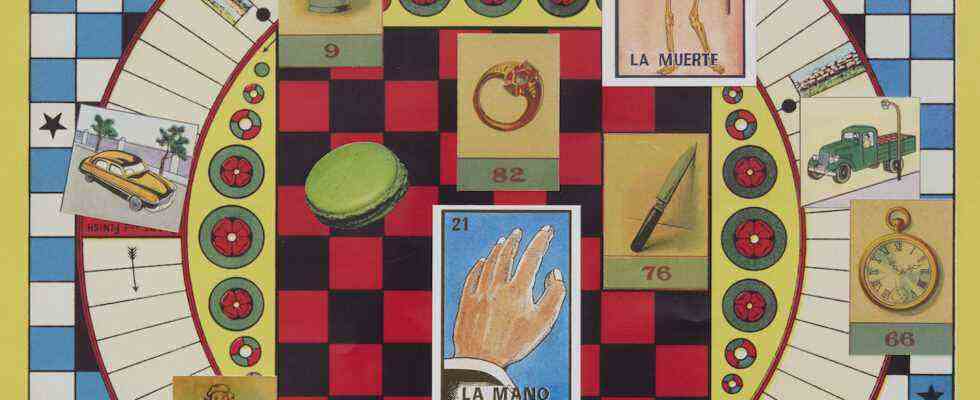

Parallel Movement of the Hands is the first selection of Ashbery’s poetry to appear since his death on September 3, 2017. Edited, introduced, and annotated by the poet Emily Skillings, who was his assistant, the volume is composed of “five unfinished longer works.” The earliest, “Sacred and Profane Dances,” three prose poems on the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25: 1–13) probably dates to the early 1950s, before the publication of Ashbery’s Yale Younger Poet’s Prize–winning debut, Some Trees. Then there is a leap of about 40 years to “The History of Photography,” written around the same time as the title poem of his 1994 collection And the Stars Were Shining. Both The Kane Richmond Project—a series of short lyrics and prose poems collaged from boys’ adventure stories and Hollywood serials starring the eponymous B-movie actor—and the 18 extant variations of “21 Variations on My Room,” which may have been intended as a part of the project, were written in 2002. Ashbery “cannibalized” a number of the lines from the latter poem for “The Handshake, the Cough, the Kiss,” which was published in his collection A Worldly Country in 2007. That same year, he wrote the 26 short lyrics of The Art of Finger Dexterity, each of which takes its name from one of the 19th-century Austrian-Czech composer Carl Czerny’s 50 piano exercises.

In other words, the vast majority of Parallel Movement—listed here in chronological order rather than in the order they appear in the book—falls squarely within the period critics and scholars somewhat misleadingly call “late Ashbery.” Each poem is unfinished in its own way. Some were simply waiting for inclusion in a collection (for example, “The History of Photography”), whereas others were parts of incomplete sequences that were probably intended to be books (The Kane Richmond Project, The Art of Finger Dexterity), and each contained line edits that may or may not have been final.

Written in relatively straightforward, discursive prose, “Sacred and Profane Dances” is an outlier, but the others, even in their various unfinished states, bear the hallmarks of Ashbery’s particular sensibility and unmistakable style, not least because they are all ekphrastic poems, a mainstay of Ashbery’s career, from “The Painter,” to “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” to Girls on the Run. No small part of the value of Parallel Movement to the general reader are Skillings’s firsthand insights into Ashbery’s compositional process as she grapples with selection, transcription, textual variants, and ultimately with the question of what it means to consider a poem finished or unfinished, now that its author is no longer here to make the decision for us. Because it is Ashbery, of course, the problem is just as much philosophical as it is philological, and the answer is far from straightforward. Can the particular “accident” of their publication in this form shine a light on exactly why that is the case?

By the 2000s, Ashbery had become a beloved and improbably popular figure: That decade, he added a Wallace Stevens Award for lifetime achievement, another National Book Award, and a Légion d’Honneur decoration to his treasure chest of literary prizes; but he was also named the first poet laureate of MtvU (a division of the broadcast network aimed at college students) and had a day named after him by the New York City Council. Yet his reputation for difficulty—established by The Tennis Court Oath and made a matter of often contentious debate by the unprecedented critical success of Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror—never quite left him.

What makes Ashbery difficult, as Marjorie Perloff observed in her review of Notes From the Air: Selected Later Poems, is nonetheless different from what makes his “modernist precursors” like Pound and Eliot difficult. It requires no supplemental linguistic, historical, philosophical, or literary knowledge to appreciate. It is also different from what makes his contemporaries, the language poets, difficult. His verse rarely relies on outright violations of the norms of syntax, orthography, or page layout to achieve its effects. Rather, it tends to be composed of grammatically well-formed units combined in such a way as to produce semantically nonsensical wholes.

The following lines (from the two short lyrics in The Art of Finger Dexterity that Ashbery titled “Parallel Movement of the Hands” and that Skillings has chosen for the name of her selection) are representative:

Don’t put me on the desk.

I was afraid I was going to die very soon,

on a paper spree. Any nice person will

die very shortly. It doesn’t really fit.

A missing dog or donkey (registered)

does the American state police talk show

no favors, just as in the past you coaxed

belligerent sweetness from the hedge and then

it was gone. Color? Why no color?

What did you expect from the microtonal

overlap of minutes? And then when it

did stand up, it was like nothing you ever imagined.Rather than figuring it all

out in one hour, pull the mud

out from under him, whether that explains

the Treaty of Hubertusburg or this or that

spring wardrobe, it’s my placebo

with all the trimmings, the way we

and others like it, just so it belongs

to us and them…

In these two poems, one sentence doesn’t obviously follow from the preceding and pronouns (“it,” “you,” “him,” “we,”) are introduced without referents. Logical connectors (“Rather,” “whether”) and comparators (“just as,” “just so”) function as red herrings, creating a certain expectation in one clause that is dashed or diverted in the next. Abrupt introjections (“It doesn’t really fit”; “Color? Why no color?”) and sudden shifts in linguistic register (the pompous-historical “the Treaty of Hubertusburg,” in contrast with the camp-domestic “spring wardrobe,” for example) disrupt apparent chains of reasoning (since they are all placebos anyway, they are interchangeable with other concepts). Intertextual play and allusions (the “voluptuary sweetness” of the “hedges” in T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” has turned “belligerent” here) do not serve to contextualize the passages in which they appear (nor is it clear what relationship these two poems bear to the musical composition they were both named after). Throughout, the conceptual structures of ordinary language are subjected to surprising category mistakes and polysemy (as when the visual “color,” the sonic “microtonal,” and the temporal “minutes” are all made to “overlap”) and common idioms are détourné (as when the “dog and pony” of the phrase “dog and pony show” become the “missing dog” and registered “donkey” of an “American state police talk show”).

If there are any clues as to what Ashbery is up to, they can be found in the phrases “It doesn’t really fit”—which could be read as self-reflexive—and “Rather than figuring it all / out”—which could be taken as a suggestion to the reader, especially if that reader is a critic. There is little hostility in Ashbery’s poetry, and where it exists, it is extremely mild, but one set of things that routinely seem to irk him are systems, theories, capital-I “Ideas,” and indeed criticism. Here the reader who tries to “figure it all / out” gets the “mud” pulled “out from under him”; in “The History of Photography,” the jargon of literary theory gets a playful ribbing and the act of reading this way is implicitly compared to a silent movie actor slipping on a banana peel. It is as though Ashbery has critic-proofed his poetry: Standard critical techniques like pattern-finding, identifying allusions, supplying biographical or literary context, and discursive reconstruction slide off his lines like water off the feathers of a duck.

Unless one resorts to cherry-picking lines out of context (a quasi-bibliomantic procedure, as New York School scholar Andrew Epstein has observed, which could be said to have been anticipated with a wink by Ashbery in “Sortes Vergilianae”), explaining what a given poem means gives way to describing how it achieves its effects or describing the experience of reading it. In the final analysis such readings will be subjective, but Ashbery provides no shortage of potential metaphors. A common one is floating aimlessly downstream in a boat, because, just as Ashbery has written, “in a boat you are never sure of arriving, or making progress” toward understanding it. Ashbery’s wager is that the reader will “inherit” such “fatal inconveniences” “with a shrug,” because the experience of “the light,” of one’s reflections “glancing off the darting waves” of his lines will be “reward / enough.”

One consequence of this mode of writing—part of its attraction to its admirers; to its detractors, a fatal flaw—is that it is easy to come away with the impression that whole passages could be added, subtracted, relocated, or substituted for others without doing noticeable damage to the overall effect of the poem. As an illustration, compare these two passages, one from the from the posthumous collection:

I don’t know—spring came and went so fast this year,

sex on the river—the chosen advice. And more.

Once the foreplay is over the real mess can begin

and one observes it. “I had no idea it was so complete,”

Mrs. Swift continued, as they passed the dock area with its

numerous boats…

and the other published during his lifetime:

I don’t know—spring came and went so fast this year,

sex on the river—and one observes it.

By the way, only minors are allowed.

Finally I just went to him and said—look,

if that’s all you can bring to the table, why are we here?

We’ve got lots to do—more than our share. You can hear cars

revving up in the next valley, but there’s still not enough time.

As Hannah Sullivan argues in The Work of Revision, ever since the widespread adoption of the typewriter by the modernists in the early 20th century made extensive editing standard practice among poets, most poems undergo several drafts before they are published. But the fact that it is difficult to tell which of the above passages is the version that happened to be published simply by looking at them suggests that in Ashbery’s case the distinction between published and unpublished does not map as neatly onto the distinction between finished and unfinished as it does for other poets. (In this case, even calling the incomplete “21 Variations on My Room” a draft of the completed “The Handshake, the Cough, the Kiss” rather than a variant would beg the question.) The logic of contingency that animates Ashbery’s formal procedures also serves to undermine the “finality” we typically associate with publication, not to mention “poetic closure” as a criterion of aesthetic evaluation. Indeed, it is difficult to think of a major English-language poet for whom Coleridge’s dictum that poetry is the “best words in the best order” is more irrelevant and less true.

It is therefore tempting to make indeterminateness what the poems of Parallel Movement, and by extension Ashbery’s late poetry, are simply about. In his forward to Parallel Movement, novelist and poet Ben Lerner writes that “it feels right…that the first volume to appear since [Ashbery’s] passing is made up of poems still in process, poems in which the resistance to finish is itself a unifying theme.” Endorsing Valéry’s view that the difference between an unfinished poem and a finished one is a difference of degree rather than kind, Lerner argues that Ashbery’s resistance to completion is a metaphor for the refusal to “end, to remain ended,” that is, a refusal to be “finished off” by death, which is said to be a common preoccupation of poets in their late periods.

One would very much like this to be true, but everything we know about Ashbery gives us cause to be skeptical, and not just because the language of “resistance” and “refusal” projects an intention onto these poems that we cannot be certain they have. Periodization, after all, is a critical fiction, and like the others it is particularly ill-suited to him. Stylistically, the “late Ashbery” is more continuous with the earlier Ashbery than the label implies. In his first two collections, Ashbery had yet to land on his signature style, but Rivers and Mountains, his third, is recognizably by the same poet as Commotion of the Birds, his last. Ashbery’s supposed discovery of poetic form in the late period ignores the pantoum in Some Trees; the fourteeners in Some Trees and The Tennis Court Oath; the sestina “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape” and the dixaines of “Fragment,” both from The Double Dream of Spring; the prose poetry of Three Poems; and the quaterns of Shadow Train. The poems of Parallel Movement refute the idea that he had given up on writing longer works after Girls on the Run.

Thematically, death is hardly absent from his earlier work (e.g., “Fear of Death,” “Two Deaths,” “Flowering Death”), and even in the poems of the late work the subject is handled with breathtaking insouciance. The attempt by critics to interpret Ashbery’s poetry through the lens of a dawning recognition of his own mortality goes back at least to Helen Vendler’s 1984 review of A Wave, which was published two years after Ashbery suffered a near-fatal spinal infection. Drawing on Finnish mythology, Vendler interpreted the apparently gloomy setting of “At North Farm,” the opening poem of the collection, as a metaphor for middle age and the traveler of the poem as the “Angel of Death.” It is a good reading, but it is as definitive as any reading of Ashbery can be, which is to say, hardly definitive. According to Ashbery, “At North Farm” was written before his illness, and could not have been a response to it. After reading Vendler’s review, he “remarked to a friend that [he] had thought these poems were really dealing with love rather than death,” though he coyly conceded that “sometimes it is difficult to tell the difference between them.”

The lines from “The History of Photography” Lerner cites in support of his argument illustrate the unavoidable hazards of critical cherry-picking: “For to be finished / is nothing,” he quotes Ashbery as saying, “Only children and dinosaurs like endings, / and we shall be very happy once it all gets broken off.” Having already noted Ashbery’s fondness for serial forms in The Art of Finger Dexterity and The Kane Richmond Project—in serial forms, variations are on principle never exhausted and endings are perpetually deferred—Lerner comments: “To be finished is to be fixed and already fading, a museum piece, a dinosaur, but that’s not the fate of all artworks, all poems; poetry can also be a machine for suspending time, a way of cheating death.”

Ashbery will let a grandiose pronouncement swell for a few lines—after all, these too are parts of language, and Ashbery was a magpie—but inevitably he pops the balloon. The passage Lerner quotes continues with a characteristic swerve: “The others, then—no no, you missed the turnoff / Into that driveway. The others must lead you now.” Pontificating about finishing and endings causes the speaker to drive past where he intended to go, unexpectedly extending his trip and breaking off his argument. Whether the speaker really is “very happy” about this is not revealed, but if history is any indication, following the lead of these mysterious “others” is unlikely to lead to a different result. A frequent scenario in Ashbery’s poetry is a voyage that does not go according to plan, either because it fails to start, because it is interrupted, or because someone gets lost along the way or forgets where they wanted to go. That by missing the turnoff the speaker simultaneously undercuts and enacts the conclusion to his argument is precisely the point. As with the difficulty of telling the difference between love and death, what we’re dealing with here is a paradox—and a very old one, at that. Ashbery’s strategy, as always, was to occupy both sides of it.

Ever since the poet-philosophers Parmenides and Heraclitus squared off at the cusp of the fifth century BCE, human beings have debated whether being or becoming, permanence or change, necessity or contingency, stasis or flux, fate or chance is the true nature of reality. While it would seem to be sheer contrarianism to place the author of “The Skaters” and “A Wave” on the side of being rather than becoming, it is worth pointing out that in Ashbery the Heraclitan “river” has its counterpart in the Parmenidean “mountain,” and that the “flow” of experience is nevertheless “charted” in recorded thought. In the 1966 poem “The Bungalows,” he had already written: “For standing still means death, and life is moving on / Moving on towards death. But sometimes standing still is also life.” The title of “The History of Photography” recapitulates the terms of the paradox, rather than deciding between them.

True, to record an event is, as Lerner says, to “fix” it in place, and thereby to condemn it to a kind of finitude that the flow of history (or time) will destroy. Not to do so is to arrive at the same result, and much more quickly. Every poem, no matter how stylistically disjunctive, is still a fixed and quantifiable collection of signs, and must be, in order to fulfill the other life-preserving function associated with works of art: translating, however imperfectly or obliquely, fleeting experience into a recorded object. Only the man “having his boots cleaned” is captured in Daguerre’s View of Boulevard du Temple—the first photograph to include people in it—and survives. “There were others / in the same street, but they moved and became / invisible” to us, hundreds of years later.

As for our driver, and all the other wanderers in Ashbery’s poetry: To fail to arrive at one’s intended destination is still to arrive somewhere. Ashbery never makes the mistake of inferring from the fact that we do not know what our fates are that we do not have them. From the very first stanza of “Two Scenes,” the poem that leads off Some Trees and thus his career, destiny does not fail to get its due: “Destiny guides the water-pilot, and it is destiny,” he writes, with unusual definitiveness. “The History of Photography” concludes with “three sisters,” who are probably Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, the Moirai (or, as Valéry would have put it, Parcae) who spin, measure, and snip the thread of each and every life. He calls them “fine and resolute.”

The image recalls a comment he made about his writing process in a 1984 interview with Bryan Appleyard, which Skillings quotes in her introduction. “I don’t look on poems as closed works,” Ashbery told Appleyard, “I feel they’re probably going on all the time in my head and I occasionally snip off a length.” Readers of Parallel Movement know something about Ashbery’s destiny, which he, when he gave this interview, did not. Namely, that Atropos would only snip the thread of his life a third of a century later, nine days after he himself snipped off a short length of poetry he called “Climate Correction.” That poem, and thus his career as a writer, ends with these five words: “but you get the point.”

This is sublime irony: How can anyone be said to get the point of a poem by Ashbery if–to cherry-pick a few lines from Flow Chart—“no two people / can agree what it means”? But when the common idiomatic phrase—variations on which appears like a refrain throughout the poems of Parallel Movement—is read with obdurate literalness, another meaning emerges: You (in other words, the generic you) get (that is, receive or come to) the point (a fixed spot in space or a fixed moment in time). Instead of writing “but you catch my drift,” a semantically and rhythmically equivalent phrase, which would have drawn attention to the digressiveness for which his poetry is known, he ends on a fixed point, that is, a full stop, the symbol of conclusions in language and life.

The task of poetry is not only to “refuse” or “resist” death. It can also be to learn how to make one’s peace with it. But there is no need to decide between these two readings or these two alternatives, and Ashbery did not do so. Perhaps that is because he had what Keats called “negative capability,” that rarest of qualities, which is what distinguishes a poetic genius from even the best critic—the ability to remain in “uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” If there is anything to be learned from reading Ashbery’s posthumous poems, perhaps it is this: The paradoxes of life are not unlike the black and white keys of a piano—they are to be played with a parallel movement of the hands.