The news this week that Tupperware is on the brink of collapse left me feeling strangely conflicted.

During my two decades as the editor of Good Housekeeping, the quest for the perfect food storage container was an ever-present fixture in both my home and working life.

I used to keep a test selection under my desk, and could have given you chapter and verse on the benefits of each brand.

But while I felt a nostalgic pang at the thought of Tupperware’s passing, I also recognised with relief that its original core customer — the dutiful housewife to whom the company remained inextricably linked — no longer exists.

Tupperware has always been an intrinsically female product.

The news this week that Tupperware is on the brink of collapse left me feeling strangely conflicted. During my two decades as the editor of Good Housekeeping, the quest for the perfect food storage container was an ever-present fixture in both my home and working life

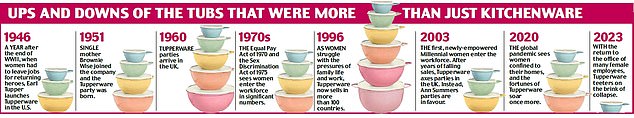

And just as women’s hemlines are said to rise and fall along with the stock market, it seems the fates of Tupperware and women have been entwined these past 70 years.

For as women’s status in society has risen, so Tupperware’s fortunes have fallen.

Strange as it may seem, in 1960s Britain the highlight of many women’s social life was the chance to buy a little plastic tub with a lid that closed with a distinctive ‘burp’.

Having swept small-town America in the 1950s, the Tupperware party proved to be a sensation: a rare chance for housewives to escape domestic drudgery and socialise with their friends over a glass of wine — and, ground-breakingly, to earn money of their own.

Even the Queen was a fan of the little plastic pots

During World War II, women on both sides of the Atlantic were encouraged to fill jobs left vacant by men fighting at the Front.

But with peace came a new social imperative: for women to give up those jobs in favour of returning heroes. Indeed, it was seen as disrespectful for women to work outside the home, no matter how tight their family’s budget.

Coinciding with this literal return to the kitchen came Tupperware — polyethylene storage tubs of differing sizes invented by Earl Tupper and launched in 1946.

In the decades that followed, it would go on to become a global phenomenon — even the late Queen was a fan.

Yet now the 77‑year-old company’s future is uncertain, having lost favour with a younger generation of women confident of their place in the workforce after the battles fought by their mothers and grandmothers, and whose eating and cooking habits are very different from those of yesteryear.

Shares in the company have fallen by more than 95 per cent in just over two years on the New York stock market, and nearly 70 per cent this year alone.

It’s a far cry from Tupperware’s heyday. After pioneering single mother Brownie Wise dreamt up the Tupperware party in 1951, thousands of women embraced the hitherto-unheard of opportunities that the brand afforded.

Coinciding with this literal return to the kitchen came Tupperware — polyethylene storage tubs of differing sizes invented by Earl Tupper and launched in 1946. In the decades that followed, it would go on to become a global phenomenon — even the late Queen was a fan

In the 1960s and early 1970s, following on from the first UK Tupperware party in 1960, the brand was highly desirable — even glamorous.

In the years that followed, the Equal Pay Act of 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act of 1975 saw women start to enter the workforce in significant numbers, and supermarkets began producing ready meals to meet demand from time-starved working women.

As Superwoman author Shirley Conran famously proclaimed, life became ‘too short to stuff a mushroom’.

Women’s rise in status perhaps diluted their interest in Tupperware, yet they still recognised the genius of the party model.

Young women had no need for ‘pin money’

In the 1980s, the late Jacqueline Gold, daughter of the owner of the Ann Summers chain, brilliantly adopted the idea of selling their wares at parties.

With women now able to buy their kitchen gadgets in John Lewis or via the Lakeland catalogue, sex toys and lingerie were a far more enticing prospect than plastic pots.

Nonetheless, with men still being viewed as the breadwinners, Tupperware rallied, and by 1996 it had reached its global peak, selling in more than 100 different countries.

It’s tempting to think of the 1990s as the era of the ladette, those famously hard- drinking young women taking on the men at their own game, with little time for — or interest in — domesticity.

But this was a conflicted time, with demands for women to be a master chef in the kitchen and a high-flyer in the boardroom (and occupy another role entirely in the bedroom).

The publication of Nigella Lawson’s How To Be A Domestic Goddess in 1998 launched an avalanche of cupcakes.

I was only too aware during my time on Good Housekeeping of the stress caused by this pressure to ‘have it all’.

Working women at the turn of the Millennium had limited maternity leave, no right to ask for part‑time hours and no financial help with childcare.

Yet as these women struggled, their daughters were growing up with very different expectations of their futures.

By 2003, when the first Millennial women (born between 1981 and 1996) were entering the workplace, attending a Tupperware party was the last thing anyone had the time — or inclination — for, and the company shelved them in the UK.

An attempt to restart them in 2011, not long after the Equality Act of 2010, came to naught.

Women were earning significant salaries elsewhere — they had no need for ‘pin money’.

However, it is striking that the biggest upheaval in society since World War II led to a brief resurgence in Tupperware.

The arrival of coronavirus saw women — and, indeed, everyone — trapped at home.

Amid a boom in sourdough baking and batch cooking, in October 2020 — after years of negative sales growth — Tupperware announced that profits were up by £26 million.

Of course, it was not to last. As women returned to work, Tupperware’s fortunes plummeted.

The social landscape has changed in so many ways since its heyday; workers of both sexes no longer habitually take their lunches to work, instead preferring the likes of a Pret or Marks & Spencer meal deal.

And ready meals and takeaway services such as Deliveroo mean leftovers are rarely stashed away in fridges and freezers.

Though the increased eco-conciousness of Gen Z should see them embrace Tupperware’s waste-saving ethos, they prefer the sleek appeal of waxed paper, glass jars and bento boxes.

With a 12-piece set of Tupperware reportedly selling for £149, who can blame them?

So although the struggles of Tupperware inspire some sadness among those who think of the iconic brand with fondness, and rightfully credit the revolutionary impact it had on its first female customers, its demise also marks the end of an inglorious era.

For today, thankfully, women no longer need a neat pile of colourful plastic containers to justify our place outside the kitchen.

The Prophet of Plastic whose parties defined a generation

by Margarette Driscoll

The storm must have rolled in quickly, because no one anticipated disaster as 1,200 of Tupperware’s top sellers set off for a beach party on an island in Florida, organised by the company’s head of sales.

Quite the contrary; if Brownie Wise’s previous parties were anything to go by, the 1957 event would be a hoot.

Tupperware’s super-saleswoman had started the annual ‘jubilee’ in the early 1950s. Attendees were awarded gifts including speedboats and fur stoles.

Brownie, a fortysomething single mother from Georgia, the inventor of the Tupperware party, was queen of all she surveyed. Until that torrential thunderstorm came in.

Scores of panicking women rushed to get off the island — leaving others stranded — and several boats collided. More than 20 people were taken to hospital and Tupperware would spend the next few years plagued by lawsuits.

The storm must have rolled in quickly, because no one anticipated disaster as 1,200 of Tupperware’s top sellers set off for a beach party on an island in Florida, organised by the company’s head of sales. Quite the contrary; if Brownie Wise’s (pictured left) previous parties were anything to go by, the 1957 event would be a hoot

Brownie’s career hung in the balance; she had already fallen out with Tupperware creator Earl Tupper. Weeks later, she was fired.

Having built Tupperware into what would become a worldwide brand, Brownie was not just a pioneering businesswoman but a feminist icon. Yet she was matter-of-fact about her achievements.

‘I needed money for me and my kid,’ she said. ‘So I got out there and made it.’

At the peak of her success, Brownie was the first woman to appear on the cover of Business Week, hailed as ‘the Prophet of Plastic’. And her Tupperware parties became the highlight of many bored housewives’ social life.

In another time, Brownie might well have ended up as one of those very housewives. Born in Georgia in 1913, the daughter of a divorced hat-maker and a plumber, she was raised mainly by her aunt.

In her early 20s, she won a competition to paint a mural at an exhibition in Texas, where she met Robert Wise, an executive at the Ford motor company. They married, but Brownie apparently found her husband to be drunken and moody.

After they divorced, she struggled to support herself and her young son, Jerry, working as a secretary, taking in lodgers and trading homemade rhubarb wine for butter.

One night in 1947, a salesman selling mops, detergents and cleaning cloths knocked on her door. His sales pitch was so hopeless she thought, ‘I could do better than that’, and applied for a job.

She was so good she soon became a supervisor. But the boss put a block on her ambition: ‘Don’t waste your time. [Upper] Management is no place for a woman.’

The firm had been flirting with the concept of home parties as a way of selling and Brownie ran with the idea. She moved to Miami and made it her own, starting Patio Parties selling homeware — including the newly invented Tupperware.

It sold so well that when supply problems depleted her stock in 1951, she rang to remonstrate with Earl Tupper, who realised that, though not an employee, she was selling more Tupperware than anyone.

He hired her as manager of the new Tupperware Home Parties division and sales soared; in 1952 her distributors, many of them housewives, took orders worth more than $2 million.

A year later, Brownie was earning more than $30,000 a year (around $273,000 today), a phenomenal sum for a woman, and was given use of a mansion by Lake Kissimmee in Florida. The fateful jubilee took place on an island just off shore.

But Brownie’s status as Tupperware’s first lady grated on Earl Tupper. He had invented Tupperware, but she was getting the glory.

The stage was set for a showdown. The disastrous jubilee came after an 8 per cent drop in sales, and in January 1958 he fired her.

Brownie later created a company selling cosmetics at customer parties, but she never reached the dizzy heights of her time at Tupperware. She died in 1992, aged 79.

Now, the era of the Tupperware party is long gone. Even Ann Summers — Tupperware’s home party successor — sells online. How Brownie Wise would have marketed sex toys is anyone’s guess.