The late David Graeber was an anarchist, an activist, and an anthropologist—and a master storyteller. Throughout his career, he explored issues of power, freedom, and social justice, usually over a lengthy period of time, and he embedded his analysis in rich, evocative anecdotes. In Debt: The First 5,000 Years, he chronicled the “everyday communism” that is the basis of human society and the ways in which various kinds of debt came to overlay it as a lever of power and injustice. In The Dawn of Everything, cowritten with David Wengrow, he proposed nothing less than an alternative origin and history for human civilization. Everything Graeber wrote was simultaneously a genealogy of the present and an account of what a just society might look like.

Graeber also put his ideas into practice. He was active in the anti-globalization protests and direct actions of the 1990s and early 2000s and became a prominent activist and theorist of the Occupy movement in 2011. He helped coin the phrase “We are the 99 percent” and often approached his activism much like his work in anthropology: by seeking to tell a story of humanity, of agency and resistance, of radical democracies and the pursuit of emancipation.

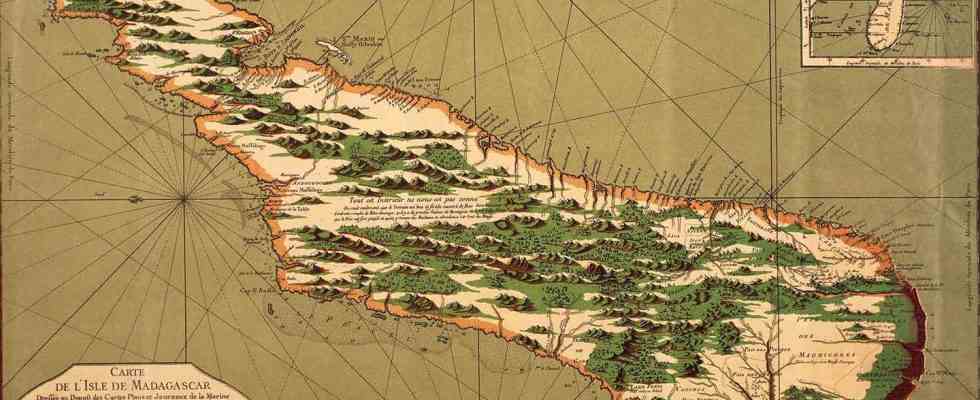

Pirate Enlightenment, a new posthumous book that Graeber had been working on before his death in 2020, weaves many of these themes into a great story. But unlike his globetrotting activism and his anthropology from the past, he does so here by situating these themes in a specific location, Madagascar, and over a much shorter time span, roughly between 1690 and 1750. Even within these confines, though, Pirate Enlightenment is an exuberant tale—one about “magic, lies, sea battles, purloined princesses, slave revolts, manhunts, make-believe kingdoms and fraudulent ambassadors, spies, jewel thieves, poisoners, devil worship, and sexual obsession,” as he writes in the book’s preface, all wrapped together in a rich sailor’s yarn about pirates and “the origins of modern freedom.” It is a book about democratic decision-making and the forms of freedom that are created from below. It also asks us to think anew about the idea of the “Enlightenment” and the origins of democracy. Rather than look to Europe, Graeber situates both on an island off the coast of East Africa.

That the history of piracy should attract someone of Graeber’s talents is remarkable. When I started working on sailors and pirates in the 1970s, it was a lonesome undertaking. Little serious scholarly work had been done on either deep-sea sailors—who were not even considered by most historians at the time to be part of labor history—or on pirates, who attracted a lot of amateur historians (some of them quite good) but few trained scholars.

The rise of “history from below” changed all that. The movements of the 1960s and ’70s—the struggles over civil rights, Black Power, the war in Vietnam, and women’s rights—demanded new histories that focused not just on states and politicians but on everyday political actors. These histories ended up democratizing how a lot of history has been written ever since. Influenced by works like E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class and C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobins, a new cohort of historians studied the “agency” and “self-activity” of a working class broadly conceived. Everyone from industrial workers to the Indigenous to the enslaved could make history too.

Piracy, of course, was only one small part of these new histories, but as historians from below began to direct their attention toward a wider variety of people, they also began to focus on a much broader geographical expanse, to move beyond the borders of a single state and across the oceans of the world. Atlantic and global perspectives began to replace national—and nationalist—accounts. Studies of maritime workers, who were usually marginal to national histories, now began to play a critical role in understanding the past. Julius Scott’s The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution was but one example of this turn, rethinking the Haitian Revolution in a wider context of Atlantic maritime struggles.Like The Common Wind, Graeber’s Pirate Enlightenment is a history from below, and one that looks beyond the traditional borders of the nation-state. The book is an essay, which means, literally, an initial attempt at understanding. It is far from definitive, as Graeber himself notes. Yet the book also has unusual strengths: It relies not only on Graeber’s graceful skill at storytelling and his acute eye for detail but also on his extensive field work in Madagascar between 1989 and 1991.

At the center of Pirate Enlightenment is the tale of a “real Libertalia.” Libertalia itself was a mythical settlement said to have been built by pirates in Madagascar as a radical democratic experiment in living freely amid the brutalities of nascent capitalism. Graeber does not suggest that this particular settlement existed but is instead interested in a real and equally subversive community that, although never called Libertalia, nonetheless thrived among the Betsimisaraka people between 1720 and roughly 1750 and was based on piratical principles.

As Graeber tells it, the history of this real-life Libertalia began in 1691, when pirates settled in Sainte-Marie, married Malagasy women, and took up the slave trade, with much of their human traffic directed to the colony of New York. Local lineage chiefs attacked and eradicated the settlement in 1697. Then Nathaniel North and his pirate crew built a new settlement at Ambonavola in 1698 based on the democratic and egalitarian practices of pirate ships. They too took Malagasy wives, and they formed alliances that would last until North’s death in 1712. Malagasy women used pirate loot to set themselves up as merchants and to establish autonomy. Graeber sees these women as having carried out a coup against the patriarchal restrictions of their culture.

The hero of Graeber’s yarn is a charismatic young man named Ratsimilaho, the son of a seaman turned pirate and a Malagasy woman who was a leading figure among the Betsimisaraka. Between 1712 and 1720, Ratsimilaho led the Betsimisaraka in a series of wars against a rival chief, Ramangano, and the Tsikoa, a southern clan that seized control of several port towns on the island’s northeastern coast in order to trade with Europeans. Ratsimilaho resembled pirate captains who projected great power and used violence against their political rivals, all the while leading his own community through collective, democratic deliberations. He used the kabary, an institution of discussion and debate, the same way that pirates used the common council to govern their ships. He also employed pirate means of warfare, including the use of muskets. Ratsimilaho soon defeated the Tsikoa, naming them the “Betanimena”—those covered in red mud—as they retreated in defeat.

Ratsimilaho’s victory over Ramangano in 1720 consolidated what became the Betsimisaraka Confederation, which for the next 30 years would conduct what Graeber calls a “proto-Enlightenment experiment.” Relying on the pirate practices of equality and antipathy to concentrated, arbitrary authority, Ratsimilaho and the Betsimisaraka created and maintained a decentralized, nonhierarchical, participatory “mock kingdom” that opposed the slave trade, established egalitarian practices, and experienced decades of prosperity.

Unlike most reviewers of Pirate Enlightenment, I have read most of Graeber’s primary sources. We agree on fundamental issues: first, that Libertalia itself was a fiction, a literary invention. This is not controversial. Second, we agree that real, empirically proven historical social practices among pirates both inspired and informed the tale of Libertalia. The ideas embodied in Libertalia were real, living conceptions. They were not utopian, which means “no place”; they had a place and, as Graeber deftly shows, they also had a history.

On minor points, we might disagree: Was Daniel Defoe “Charles Johnson,” the author of General History of the Pyrates and its section on Libertalia? Graeber suggests that he likely was, but I don’t think so: Johnson’s book contained more detailed maritime knowledge than Defoe could have possessed or even understood. The section on Libertalia was probably the work of a team of Grub Street writers in London who had connections to actual pirates whom they interviewed for the book, as well as access to unpublished manuscripts that were circulating in official circles. Yet none of this undermines Graeber’s larger argument: that between 1720 and 1750, a radical democratic society popped up like a hydra head in Madagascar.

Pirate Enlightenment does have other limitations, however. Much of the history treated by Graeber is not only unknown but unknowable, as he freely admits. Moreover, I doubt whether there were as many pirates in Madagascar as he claims; “several thousands” seems completely impossible to me. I doubt the number was even “many hundreds,” since only around 5,000 pirates sailed the seas anywhere in the period that Graeber studies. These numbers matter, because the argument about the impact of pirates on the cultures of northeastern Madagascar depends to some extent on a density of physical presence: The smaller the number of former pirates, the less likely and the less long-lasting their influence would have been. I might add that the pirates who settled in Madagascar were only a small minority of the total pirate population between 1650 and 1730, the so-called “golden age,” and that Atlantic pirates were much less involved in slave-trading than those who based themselves in the Indian Ocean.

It is also important to remember that “pirate culture” (the way of running a ship) was itself a dynamic phenomenon that changed over time. Three distinct generations of pirates made up the “golden age.” There were continuities in their cultures, but they were not identical by any means. As the buccaneers of the 1660s and 1670s gave way to the pirates of the 1690s, who were followed by those of the 1710s and 1720s, pirate culture became more egalitarian and democratic over time, as elites dropped out of the business of robbery by sea and common seamen gained greater control over the operation of pirate ships. It is crucial that the pirates who did settle in Madagascar during the 1690s (however many of them there were) did so at a time when big merchants and slave traders still had a lot of power over their actions.

A question that runs through Graeber’s narrative but is never fully addressed is the practice of enslavement among the Betsimisaraka. Graeber argues that part of Ratsimilaho’s successful project was to disconnect his region and people from the increasingly aggressive slave trade in the Atlantic and Indian oceans. But Graeber does disclose evidence that Ratsimilaho and his fellow warriors possessed slaves, which, if true, would make his “experiment” less democratic than Graeber claims, and one not outside the slaving systems plying the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Despite these reservations, I find Pirate Enlightenment one of the most creative books ever published on the history of piracy. The main reason is that Graeber offers new ideas and fresh insights about the history of these maritime outlaws. Most books on pirates have no new ideas, and some have no ideas at all, just research findings, which are useful but limited. What Graeber offers that is new is a discussion of how the process of change involving pirate culture worked among the Betsimisaraka—how the peoples of northeastern Madagascar were knowing, conscious agents of history who made choices of inclusion and transformation within the matrix of their own values and culture. One of the strengths of Graeber’s book is his analysis of the structure and culture of Betsimisaraka society and how it changed over time. Even when he lacks sources about specific people, events, and times, I find Graeber convincing. He did his fieldwork; he had a working knowledge of the Malagasy language; he had long-standing intellectual and cultural engagements in Madagascar. He successfully pairs two kinds of history from below: maritime and Indigenous. This is a highly unusual combination and a winning one. He treats ordinary people, especially women, as thinkers, creators, and makers of history. His theory and methods are as democratic and egalitarian as the culture he seeks to illuminate.

I hasten to add that I am not a specialist in the history of Madagascar and that the influence of Graeber’s book will depend to a large degree on what scholars of the Betsimisaraka have to say about it. Graeber has offered an interpretation that seeks to make the most sense of the available surviving evidence about pirates and the Betsimisaraka over a long span of time. He may be wrong in some particulars, but I suspect his overall interpretation will be hard to refute.

Like his histories of debt and the dawn of “everything,” Graeber’s Pirate Enlightenment provokes us to think. At the same time, some of Graeber’s ideas are not as new as he claims, while others are bigger than he allows. To say, as he does, that the egalitarianism of pirates was not a “Western” ideal is not a new idea. More than 20 years ago, Peter Linebaugh and I argued in our book The Many-Headed Hydra that those principles of social and political organization were created, preserved, and re-created by a multiracial Atlantic proletariat in a long series of struggles from roughly 1600 to the 1830s. Throughout the 18th century, a tradition of maritime radicalism consistently offered new political possibilities: among pirates in the 1710s and 1720s; in the port city rebellions of the 1730s; in the American Revolution of the 1760s and 1770s; and in the massive, Atlantic-wide naval mutinies of the 1790s. Graeber does not inquire into the origins of pirate culture, although he does note that freebooters offered “a profoundly proletarian vision of liberation.”

On the other hand, Graeber’s point about “enlightenment” is much bigger than he claims. The idea of an “Enlightenment from below” is much older than the pirates of the late-17th- and early-18th-century Indian Ocean. A key moment in this kind of enlightenment goes back to the earliest contacts among European seafarers and the peoples of Africa and the Americas. Transoceanic reports of stateless and classless societies had a profound impact on the development of European social thought. Book two of Thomas More’s Utopia was narrated by a sailor named Rafael Hythloday, who had just returned from the sea to share his knowledge of a people who lived without private property. Michel de Montaigne published his great “humanist” essay “Of Cannibals” in 1580, about the Tupinambá people in Brazil—in which he inverted the common sense of the day and argued that the real cannibals were not the Indigenous people but rather Europeans. His argument was shaped by stories told to him by his servant, who had worked as a sailor on a voyage to Brazil. Meanwhile, Shakespeare went down to the docks as he wrote The Tempest and talked to sailors about the wreck of the Sea-Venture, which provided the framework for his play. Sailors were vectors of enlightenment long before the Betsimisaraka Confederation. If the formation of that confederation was a “proto-Enlightenment experiment,” as Graeber says, it was one among many.

Here is a final irony: Pirates lost the battle in their own day. The ruling classes of the Atlantic hanged them by the hundreds in deliberate acts of state terrorism. Their bodies dangled in port cities around the world as a warning to those who attacked merchant property and dared to run their ships in a new and democratic way. Many pirates taunted the authorities from the gallows; they embraced “a merry life and a short one.” But here we are, 300 years later, still debating the meaning of what pirates did and why they did it. We do not remember the names of the capitalists and the imperialists who hanged them. In this sense, pirates may have lost the battle, but they won the war for historical memory. There is justice in that, and there is something fitting, too, that this is the ultimate message one gets from David Graeber’s final book.