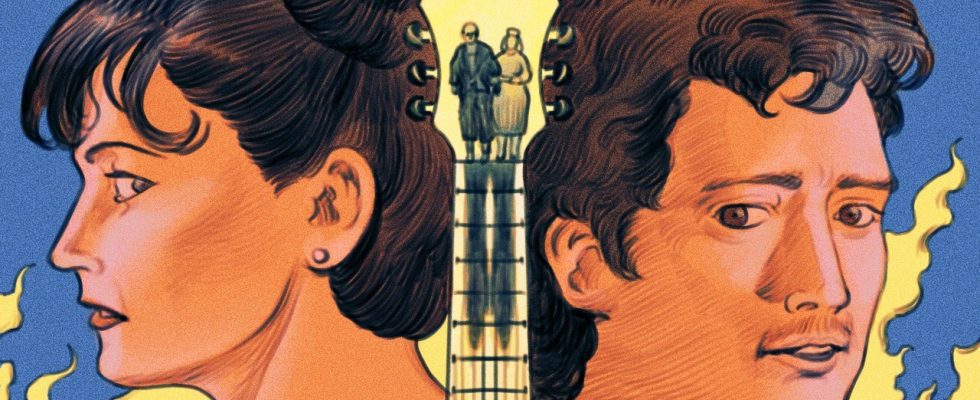

“Orpheus Descending,” a great big louche mess of a play by Tennessee Williams, from 1957—revived at Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center, directed by Erica Schmidt—kicks into gear when a good-looking kid called Valentine Xavier (Pico Alexander) slinks into the Torrance Mercantile Store, in a small town in Mississippi. I say “called,” not “named,” because he seems like the type of guy who’s had to shed his given name like a skin, and maybe a handful of others after that, continually improvising. Self-created and just turned thirty, he’s decked out in a snakeskin jacket, carrying a much loved acoustic guitar. Val’s an odd guy, shrouded in put-on mystery and spouting high-flown, lyrical talk.

In search of a job, he produces a reference letter that’s off-puttingly candid: his former employer at an auto-repair shop says that he is “a peculiar talker and that is the reason I got to let him go.” As for himself, Val offers, “Well, they say that a woman can burn a man down. But I can burn down a woman.”

Val has been brought to the store by Vee Talbott (the very funny Ana Reeder), who is a painter of her own sacred visions—she’s toting a picture of a headless Holy Ghost—and the wife of the local sheriff (Brian Keane). Whatever we think of Val’s assessment of his own magnetism, it’s clear that it’s working on Vee. She shows him off like a prized cut of steak, trying to help get him work at the store. The place is owned by Jabe Torrance (Michael Cullen), a mean man with an unlovely personality who’s just returned from having surgery in Memphis and seems to be dying. Jabe’s middle-aged wife, Lady (Maggie Siff), an all-business daughter of Italian immigrants, runs the store with efficient competence in his stead. When Jabe needs something, he bangs on the floor of his room upstairs, rattling the ceiling of the store. It’s Lady to whom Val gives the recommendation letter and the spiel about his sex appeal.

Whatever trick Val’s got up his sleeve, he’s turned it before. At the shop, the flighty and booze-addicted Carol Cutrere (Julia McDermott, who plays the part with heart) recognizes him from a long-past night in New Orleans. She’s heard him sing and play that guitar, and obviously harbors lovelorn memories. Soon, the brazen Carol is frankly asserting her desire to get to know Val better this time around. Val doesn’t appreciate the reminder. He insists that he’s left those wilder days behind, that his recent escape from his twenties means an end to the fast, itinerant life.

Carol glides around the edges of the play like a spectre, and there are more ghosts than one: she cavorts with Uncle Pleasant (Dathan B. Williams), a largely silent Black “conjure man” who is “part Choctaw” and who, if prompted by cash, will offer a piercingly loud Indigenous chant. But the major artery of the eventually bloody play is the relationship between Val and Lady. She hires him, even as she scoffs at his braggadocio. “Just remember,” she says. “No monkey business with me.” And yet, in short order, we see the power in the relationship shift, as the older woman becomes more and more bewitched by the younger man.

So much depends, in this play, on whether you buy the idea that a woman like Lady would make herself abject—go almost mad and endanger her life—over a truant kid like Val. Lady is from an immigrant family, and holds tightly to the memory of her father, a merchant whose “wine garden” was burned down by the Klan because of his willingness to do business with Black customers. Her father went up in the flames, too. This is a flagrantly racist town: the N-word flies almost casually throughout the text of the play, the better to show a kind of rattlesnake viciousness in the town’s citizens, and their saturation in the culture of Jim Crow. Lady stands apart from that culture, thriving commercially but remaining ethnically distinct. She speaks with an accent and wears the dark colors of a mourner.

Siff’s performance reflects the double-sidedness of Williams’s text. One minute, Lady is formidable, and the next she’s a comic whirlwind, telling jokes and making faces, set ablaze and made a fool by Val. Siff is a powerful performer who maintains a taut string of connection with the audience. When she’s kidding, you laugh; when she’s thinking, you strain to find the meaning written on her face. Lady’s backstory and Siff’s dignified conveyance of her physical presence elicit respect from the audience. She’s been through a lot and seems hard to deceive. Her father’s lost wine garden becomes her model for the shop’s new confectionery—a sweet, symbolic revenge that just might make a mint.

So it’s difficult to see what’s so alluring, in her eyes, about Val. Yes, he’s wearing a cool jacket, and we’re supposed to discern in his bearing a familiar bad-boy charm. Maybe it’s too familiar: scrawled on his guitar are the signatures of famous blues and roots artists, like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Woody Guthrie, and Bessie Smith. You can tell that he’s jacked some of his swagger from these betters of his, and employs it on women too provincial to know the difference. Here’s some of the “peculiar” talk that’s supposed to pass as a first step in seducing Lady:

He also claims to be able to go forty-eight hours without sleep—“without even feeling sleepy”—and three minutes without taking a breath, and a whole day without using the bathroom. In order to contemporize Val and have him make any cultural sense, you’d have to reach for the recent trope of the “fuckboy”—that jerk who trawls the streets of Bushwick, tells stories about himself and shares surprising facts at trying length over the din of the bar, and makes promises he never means to keep. His playlists always include Drake, and, like Val with his jacket, he cultivates a wardrobe full of statement outerwear. Sometimes Val sings snippets from a song called “Heavenly Grass” while strumming his guitar, and you can see, instantly, the romantic effect it has on Lady. I’m not sure the spell ever reaches beyond the lip of the stage.

This disjunction isn’t Alexander’s fault, or Schmidt’s. The direction is fluid and affecting, and Schmidt goads her actors into creating moving tableaux reminiscent of the most menacing of Norman Rockwell’s paintings. (She’s helped in this by David Weiner’s high-contrast lighting and Amy Rubin’s scenic design.) The problem is that Val is an all but lost artifact of our cultural memory, one whose existence was a cornerstone of twentieth-century American literature—the strong, emotional, mysterious man whose sexual appeal and moral courage are as natural as a Southwestern rock formation, as ubiquitous as landscape itself. Not anymore. The best recent pop-cultural example of a man like this—Don Draper, in “Mad Men”—was unclothed, piece by piece, until we could see him for the fraudulent little boy that he was.

The passage of time has made Williams’s shrewd, operatic, utterly human women even more appealing—and, strangely, made his men look like paper dolls, useful only to stoke crises in the lives of their more interesting and soulful counterparts. Val’s Rorschach masculinity just won’t fly, and it is easily the most dated thing in “Orpheus Descending,” racial slurs included. Williams wrote Val as a victim of his own allure—he can’t help how all these women react to him, or how their desire brings about an all but certain doom—but, when Val appears on a contemporary stage, he’s the deserving victim of feminism’s successes in dressing down facile notions of what it means to be a man. ♦