This is an edition of Up for Debate, a newsletter by Conor Friedersdorf. On Wednesdays, he rounds up timely conversations and solicits reader responses to one thought-provoking question. Later, he publishes some thoughtful replies. Sign up for the newsletter here.

Question of the Week

What role should sports play in society, and/or what’s your assessment of the role they play in ours? Feel free to comment on professional, recreational, or youth sports; on team, individual, or extreme sports; on playing, watching, or boycotting sports; or anything else on this subject.

Send your responses to [email protected] or simply reply to this email.

Conversations of Note

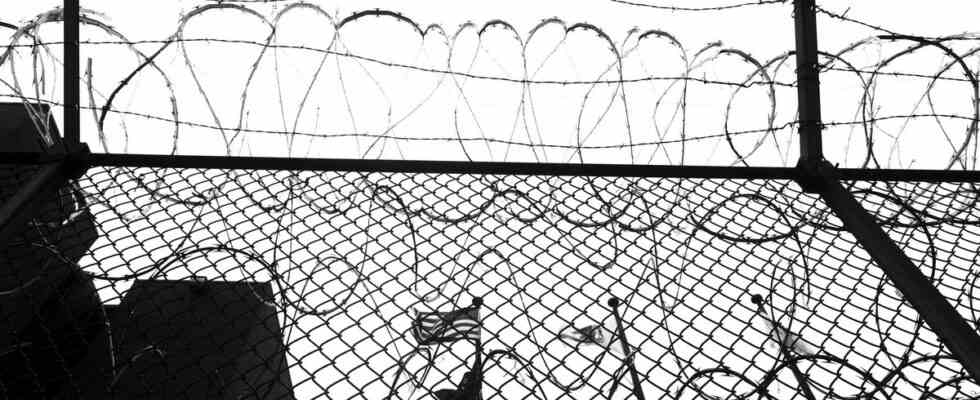

This newsletter usually highlights stand-alone articles, but my colleague Elizabeth Bruenig’s exemplary case against the death penalty is best understood by perusing her body of work over time.

Begin with “Not That Innocent,” where the premise is that “most people on death row are guilty” but “that doesn’t mean they deserve their fate.” In her assessment of the condemned, “innocence cases indicate that some capital sentences are unfair,” but failing to look beyond those cases can obscure the evidence that “a fair capital sentence is virtually impossible,” as suggested by “decades of studies on death-qualified juries; race, gender, and immigration-status bias among jurors; law enforcement and prosecutorial misconduct; weak forensic science and poor representation at trial.” For opponents of the death penalty, “the fight should be waged not against particular injustices,” she argues, “but against the unjust system itself.”

Subsequent articles highlight concerning aspects of that system.

In “The State of Texas v. Jesus Christ,” Bruenig highlighted an effort to deny a pastor the ability to pray aloud and lay hands on a condemned man during his execution. Her assessment of that legal fight:

A pastor praying aloud, holding a dying man’s hand, would bring too much flesh, too much humanity, into the thing. Execution theater is all about maintaining the illusion of mechanism. And if the [Supreme] Court rules that the state’s preference for executions with the aesthetic aspirations of a medical procedure outweighs Ramirez’s desire for a Baptist pastor to lay hands on and pray over him as he is killed, it is precisely that fleshly, embodied, humane tradition of accompaniment—even for scoundrels—in Christianity that the Court will deny by the letter of the law.

Redirecting her attention to a neighboring state in “Oklahoma Tortured John Grant to Death Because He Wouldn’t Commit Suicide,” Bruenig highlighted the jarring practice of states asking death-row inmates to name the method by which they want to be killed, and how that approach came about:

Since the Supreme Court’s strange and consequential opinion in the 2015 case of Glossip v. Gross, in which Justice Samuel Alito wrote that “because capital punishment is constitutional, there must be a constitutional means of carrying it out,” death-row prisoners who challenge their states’ methods of execution have been tasked with producing a suitable alternative … The Eighth Amendment, which theoretically bars cruel and unusual punishment, ought to—at least, per the interpretation of the Supreme Court—move the country ever further toward humane and civilized justice. Yet challenges to methods of execution that have produced clearly cruel deaths—such as that of John Grant (and others before him, including Clayton Lockett, also of Oklahoma)—have resulted in a freakishly sadistic execution schema in which people aren’t just killed by the state but are also recruited as participants in their own demise, in clear violation of their religious principles and despite the obvious psychological terror such a regime inflicts.

In “A Good Man, at One Time,” she writes about David Neal Cox, a Mississippi man who committed horrific crimes and became an advocate for his own execution. The essay defies easy summary, except to say that it probes a case as friendly to the perspective of death-row supporters as can be imagined and bites associated bullets, yet still finds striking moral complexity. (Bruenig gamely grapples with another tough case in “Should the Parkland Shooter Die?”)

Most recently, in a series that includes “Can America Kill Its Prisoners Kindly?,” “Two Executions on a Thursday in America,” “Dead to Rights,” and “Dead Man Living,” Bruenig bears witness to executions. In effect, she convinced me of an argument she makes in the first of those pieces:

Among all the amendments in the Bill of Rights, the Eighth may be the noblest, because it ensures the protection of condemned criminals, the most friendless and vulnerable people. And it should be vindicated, not only for their sake—though mainly so—but also for our own.

In any of the executions described in those pieces, consider the psychic costs that state killing imposes on the judges, the executioners, the families of the condemned, and the witnesses, as well as the many millions of Americans who are troubled by killing done in their name.

Great-Power Struggle

Jonathan Last argues in his Bulwark newsletter, The Triad, that the Biden administration has stymied China’s power in a significant and underappreciated way with the new export controls that it announced last week. Last explains:

Making computer chips requires a lot of advanced equipment. Much of that advanced equipment is made by American companies. The new rules from the Biden administration make it so that any company, anywhere in the world, using certain advanced American equipment to make chips can’t sell those chips to Chinese-controlled companies … At the stroke of a pen, China is getting cut off from the kind of advanced chips it can’t manufacture on its own. Which will cripple both military progress and tech-sector progress, too.

Sports and Gender

Today’s “question of the week” about sports was inspired by an emailer who wrote this during our discussion on what ails men and boys:

I wonder about the effect on males of zero-sum competition and “hero” worship inherent in organized sports. If it’s impossible for the vast majority of men to be winners, they must either identify as losers or subsume their own value to that of the winner they’ve chosen. That pervasive, hypercompetitive model of being seems fundamentally flawed.

Reflecting on my years playing various competitive youth sports––soccer, basketball, and tennis most of all––it seems to me that among the most valuable things it taught me was how to lose well and that one can enjoy competing at many things without being the very best at them.

For a thought-provoking essay from a different perspective, see “Nike’s End of Men” by Ethan Strauss, which probes the relationship between pro sports, sports marketing, and gender.

Learning Your Limits

At Persuasion, Freddie deBoer makes the case that failure is an important but underappreciated part of higher education:

Recently, an adjunct professor at New York University was fired. Once a celebrated tenured chemistry professor at Princeton, Maitland Jones Jr.’s employment at NYU was cut short because of a student petition. The students complained of an imperious attitude and lack of flexibility, but the fundamental issue was that Jones’s Organic Chemistry course was simply too hard—too many students failed, and too many students who were used to receiving As received Cs. It was a direct conflict between Jones’s standards and his students’ expectations of their own success.

This firing over a question of educational rigor has inspired a lot of concern, including from me. Of course, as this is a culture war issue, some have taken to the ramparts to insist that the fired professor must have been a bad teacher if so many students rebelled … Whatever the case, I want to suggest that the students who launched the petition were denying themselves a central element of education: figuring out what you’re not good at. Failing. Trying to learn, and failing to do so. This is an element of education as vital as learning what you’re good at, the act of self-discovery of one’s own lack of ability. All of us have limits, natural limits on what we can learn and do in academic fields. Some exceedingly rare individuals appear to be brilliant at everything, but for the rest of us, there’s a whole suite of topics and skills that we will never perform with any facility. And if colleges insist on reducing rigor to the point that learning those limits becomes impossible, something will have been lost.

Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day

I’d thought that every angle in this annual debate had been exhaustively aired years ago, but Scott Alexander managed to break new ground in a delightfully dialogic post over at Astral Codex Ten.

Overwhelmed by the Culture

That’s how the essayist, podcaster, and longtime cultural critic Meghan Daum is feeling for reasons that she explains at The Unspeakable:

Once upon a time I might have been described as someone who “inhaled culture.” In my twenties, as the internet was just beginning to peek out over the horizon, I had a pretty solid grasp on the “arts scene,” as we called it … I knew what films were in theaters … what important novels had just come out, what shows were worth watching on television, what venues my favorite musicians were playing, what big shows were at the big museums and even what was being performed on Broadway or at the Metropolitan Opera—not that I ever went. Back then, I went to the movies at least twice a week … One of the great pleasures of my filmgoing was rereading the reviews after having seen the movie … Suddenly you understood the big picture. You knew what everyone was talking about. Somewhere in the mid to late aughts, it stopped being possible to know what everyone was talking about. For at least the last decade I haven’t known what anyone is talking about and for the last several years I haven’t really cared.

There is, indeed, a torrent of content out there––amid it all, thank you for choosing to read Up for Debate.

Ask Me Anything

As an experiment, I’ll be trying to incorporate some of the questions you ask me into the newsletter. Reflecting on proposals to get more men into caregiving professions and more women into STEM, Brian, a reader, expresses support for both goals but discomfort with one way of achieving them.

He writes:

I am super wary of so-called positive discrimination, and I therefore feel very conflicted about Richard Reeves’s proposal that we provide scholarships to men to move them into HEAL [health, education, administration, and literacy] subjects and offer funds to HEAL employers to encourage them to hire more men. I see the benefits, and I agree that there appears to be a need for doing it. But I still have a hard time getting past the discriminatory approach. Likewise, while it seems clear that scholarships have moved more women into STEM positions, efforts to increase representation have also been found to be discriminatory against men.

My feelings about such practices, and whether or not they’re fair and/or justified, are very mixed. How would you respond to the argument that both STEM scholarships for women and HEAL scholarships for men discriminate based on sex? I mean, clearly they do. But is it justified? When is positive discrimination acceptable, and when is it unacceptable?

There are at least two distinctions that inform how I think about these cases. One concerns the reason for seeking greater sex parity in a field. Is it because, as in early-childhood education, proponents believe that having more men or women will improve how well the job gets done? If so, that strikes me as a stronger case for affirmative action than instances where the driving force is a desire for sex parity as an end in itself, and would strengthen the case for something like privately funded sex-specific scholarships. The other distinction concerns method. Is the approach to attract a more sex-diverse applicant pool and fill openings in a nondiscriminatory manner, or are individual job candidates discriminated against? I tend to favor efforts to diversify hiring pools and oppose sex discrimination against individuals.

Provocation of the Week

Esau McCaulley, a professor at Wheaton College, cares deeply about how ideas are presented to his children at school, but cautions against focusing on what material is taught. Instead, he counsels, consider whether students are given permission to think about whatever is taught:

How do we order society in such a way that increases human flourishing and limits suffering? What is the good, the true and the beautiful? How do we make sense of the sins of the past and the way the legacies of those failures follow us to the present? What is justice? What is love and why does it hurt us so? What is the good life? Is there a God who orders the galaxies, or did we come from chaos, destined only to return to it?

The answers to those questions that I received from my teachers varied. I do not judge the worth of my former educators by whether I agreed with them. I value those who made me think and did not punish me when I diverged from them … If parents and politicians truly care about their children’s education, they should not only ask what a teacher said about a controversial issue, they should also ask how the teacher said it, and whether students were assessed based on the quality of their work rather than conformity to a particular ideological perspective. This ability to hold fair and stirring conversation is the gift that all great teachers have. It is impossible to legislate. This is a gift that can either be honed or ground to rubble by unrelenting competing agendas. We must protect teachers who do it well and do not so overburden and underpay them that they despair of their vocation.

This perspective dovetails nicely with the educator Erin McLaughlin’s advocacy for a viewpoint-diversity curriculum.