Whether it’s by translating forgotten texts or uncovering lost artefacts, archaeologists are constantly edging towards a better understanding of the past.

Yet even as archaeological techniques advance, some mysteries have remained stubbornly mysterious.

From the bizarre Roman ‘holey jar’ to unexplained six-foot stone spheres in Costa Rica, the origins and uses for some artefacts have been long since lost to time.

But much to archaeologists’ frustration, the lack of evidence has not stopped wild theories and rampant speculation surrounding these five baffling objects.

Lorena Hitchens, an archaeologist and PhD candidate at Newcastle University, told MailOnline: ‘For some people, an unsolved mystery is really hard to accept.’

From the strange ‘holey’ Roman jar to the six-foot tall stone spheres of Costa Rica, these five strange objects still baffle archaeologists to this day

The Towie Ball

When you think about archaeological mysteries, your mind might leap to grand structures like the Library of Alexandria or the city of Troy.

But in reality, some of history’s most fascinating and mysterious objects are much more simple.

The Towie Ball is a 531g (1.2 lbs) ball of black stone believed to have been carved by Neolithic people in Scotland more than 5,000 years ago.

Three of the ball’s four carved faces are marked by intricate swirling patterns while the last remains strangely blank.

Despite being discovered in 1860, the reason this strange object was made largely remains a mystery.

The Towie Ball (pictured) is a 531g (1.2 lbs) ball of black stone believed to have been carved by Neolithic people in Scotland more than 5,000 years ago

What makes this puzzle all the more frustrating is that this is just one of around 430 different stone balls found mainly along the eastern coast of Scotland.

While hundreds were found, many were considered curios and were sold or sat gathering dust in private collections.

This has made it difficult to know exactly where and when they were made, adding another layer of confusion for archaeologists to contend with.

One popular theory is that these were a form of high-status weapon among stone-age people in the area.

Writers in the 19th Century thought that the grooves could have held ropes used to convert the stones into mace heads or load them into a sling.

A 2007 research paper even suggests that their rough surface could have been intended to reduce air resistance and make them more deadly as thrown weapons.

However, in a recent book on the stone balls of Scotland, Dr Chris Stewart-Moffitt of the University of Aberdeen points out that these theories ignore key evidence.

Not only are the balls remarkably undamaged despite their great age, but other random stones would have been just as effective as weapons without needing to be carved.

Dr Stewart Moffitt writes: ‘We have no actual proof that they were used offensively or defensively… to consider them to be weapons is to seriously miss the point.’

Instead, Dr Moffitt suggests that the balls could have had a symbolic rather than practical purpose.

He suggests that the round shape could have evoked the circular shape of homes while the ridges may have stood for the hills and valleys of Scotland.

However, despite our best guesses, the true origin of these objects is likely to remain lost to time.

Nobody knows quite why this object was created but recent studies propose they had a symbolic purpose, with the grooves representing the rivers and valleys of the Scottish landscape

The Antikythera mechanism

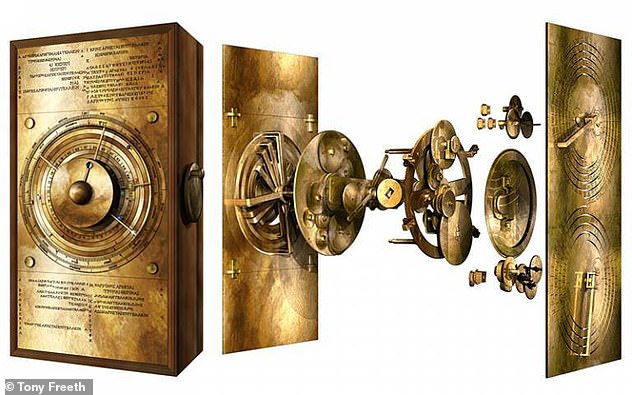

The origins of the Antikythera mechanism sound like something straight from the pages of a thriller novel.

In 1900, a group of sponge divers were taking refuge from a sudden storm near the island of Antikythera, not far from modern-day Crete.

When the storm subsided and the divers decided to try their luck near the island, they stumbled upon a shipwreck laden with beautiful stone statues.

But, almost forgotten among those other treasures, subsequent excavations found a book-sized lump of corroded metal.

When experts at the National Archeological Museum in Athens split the metal apart, it revealed an intricate construction of precision gears and dials.

Containing 30 gears, some with teeth no more than a millimetre wide, and thousands of carved characters, the Antikythera mechanism is staggeringly complex.

Believed to date back to at least 60 to 70 BC, it was not believed possible that the ancient Greeks were capable of creating such a device.

The Antikythera mechanism was found submerged in an ancient shipwreck near the Island of Antikythera, not far from modern-day Crete

Believed to date back to at least 60 to 70 BC, this mechanical computer contains 30 gears with teeth as small as one millimetre

More than 100 years of research has revealed that the so-called Antikythera mechanism is actually a highly complex astronomical calculator.

In a 2021 paper, a team of UCL researchers used X-ray images and ancient Greek mathematical analysis to reconstruct what the device may have looked like.

They claimed that it is ‘a mechanical computer of bronze gears that used ground-breaking technology to make astronomical predictions, by mechanizing astronomical cycles and theories.’

This complex mechanism could predict the movements of the sun, moon, and the five planets known to the Ancient Greeks with incredible detail.

Lead researcher Professor Tony Free and his co-authors add that this ‘creation of genius’ combines Babylonian astronomy, Platonic mathematics, and ancient Greek theories of astronomy.

Experts have reconstructed the device’s design and claim it was used to work out the locations of the sun, moon, and five planets known to the Ancient Greeks

While we now know what the device was used for, many mysteries still persist.

Most notably, researchers are yet to determine why it would take centuries for anything this complex to be reinvented.

Even more baffling is the fact that the Antikythera device remains the only object of its type to have been discovered.

There would have certainly been earlier or later models of similar devices made, but these have remained frustratingly elusive.

Ultimately, as the researchers conclude in Scientific Reports: ‘It challenges all our preconceptions about the technological capabilities of the ancient Greeks.’

No object like it has yet been found, raising the question of why it took centuries for ancient scientists to create anything as complex

The holey jar

The so-called ‘holey jar’ is exactly what it sounds like: a jar with holes in it.

But experts are still baffled why this 1,800 year-old Roman jar would have been made riddled with holes.

The jar was found shattered into 180 pieces and was painstakingly pieced back together by experts at the Museum of Ontario Archeology.

But, even putting this strange object back together didn’t shed any light on the mystery.

Katie Urban, one of the researchers at Museum of Ontario Archaeology told LiveScience: ‘Everyone’s stumped by it, we’ve been sending it around to all sorts of Roman pottery experts and other pottery experts, and no one seems to be able to come up with an example.’

The ‘holey jar’ is believed to be a 1,800-year-old Roman artefact, but no expert has yet been able to come up with a theory as to what it could have been used for

Some theories propose that it could have been used by the Romans to store live dormice while they were fattened up to be eaten.

The problem is that other dormice jars from the Roman world are quite different, and were equipped with interior ramps to help the rodents run around.

The matter is made worse by the muddled history of the jar’s discovery.

In the 1950s, archaeologist William Francis Grimes gave the jar to the museum, saying he had dug it out of a World War II bomb crater near a Roman temple to Mithras.

But Ms Urban says this is uncertain since the vessel does not appear on the list of artefacts given by Grimes to the museum.

And with its origins shrouded in mystery and nothing to compare it to, the intended use of the holey jar remains unknown.

It was claimed to have been found near a temple to Mithras in London (pictured), but the evidence for this is doubtful – leaving its true origins a mystery

Roman dodecahedra

From walls and aqueducts to roads that are still followed to this day, the Roman occupation of Britain left behind an indelible mark on the country.

However, not all of the artefacts left behind by four centuries of Roman rule are so easy to interpret.

Some of the most puzzling objects from the Celtic fringes of the Roman Empire are a series of 12-sided objects simply known as Roman dodecahedra.

So far, 33 of these unusual objects have been discovered in Britain including a recent discovery of a 3in-tall (8cm) bronze dodecahedron found in Lincolnshire.

While the objects vary in size and decoration they frequently have a series of different-sized holes on each face and round balls on each corner.

As beautiful and fascinating as these objects may be, studying them has proved to be a fiendishly difficult challenge.

In the UK, archaeologists have found 33 12-sided shapes believed to have been made during the Roman occupation of Britain, but their purpose is unknown

Lorena Hitchens, who is studying Roman dodecahedra for her PhD at Newcastle University, told MailOnline that the true use of these objects is ‘still a mystery’.

Ms Hitchens says: ‘Romans did not visually depict or write about dodecahedra. There are no inscriptions, texts, or images.

‘It would be great if a mosaic, painting, or long-lost classical text were discovered that explained everything about dodecahedra! It doesn’t seem likely at this point, but you never know.’

The puzzle has been made even more difficult by the fact that they were highly prized by collectors in the 18th century.

The resulting ‘horse trading’ means that many of the artefacts became divorced from their archaeological context, making it tricky to piece the details together.

While they vary in size, most of the dodecahedra have different-sized holes on each face and balls attached to the corners

Finding new dodecahedra buried in their original location could be extremely valuable to understanding these objects.

The Norton Disney Historical and Archeological group, which discovered the most recent object, plan further excavations this summer which could reveal more details.

The dodecahedra are also unique in their design, which means that archaeologists have nothing to compare them with to shed light on their potential usage.

This hasn’t stopped various non-academic sources from making all sorts of comparisons to modern objects.

Ms Hitchens says that the guessing game approach has led to ‘an unproductive, frustrating guessing game with no proof in any direction.’

She added: ‘This kind of speculation is not based on real evidence. Sometimes people see what they want to see when they look at dodecahedra.’

One of these strange objects was recently featured on the BBC’s Digging for Britain, in which Professor Alice Roberts (pictured) was baffled by the bizarre object

For example, in what Ms Hitchens says is her least favourite suggestion, it is often claimed that they were used as a type of knitting aid.

While it is possible to use the balls on the corners of the object to weave tubes of material there is no evidence that these objects were ever used in this way.

Ms Hitchens says that her own research is making progress and has yielded new data but any definitive answers are still a long way off.

She concludes: ‘Will we ever solve it? I can’t say yet, but, can we understand them better than we do now? Absolutely.’

The Diquís Spheres

Any fan of Indiana Jones will know that an archaeologist’s biggest nightmare is a large round boulder.

That has proven true of the Costa Rica stone spheres, often called the Diquís Spheres, which have have resisted understanding for almost a century.

But while Indy might have spent his days fleeing boulders, archaeologists from all around the world have flocked to the island Isla del Caño and the Diquís Delta where hundreds can be found.

Almost perfectly round and up to two meters (six feet) tall, no one knows why so much effort was put into carving these bizarre objects.

Costa Rica is home to hundreds of carved stone spheres, some up to six feet tall. However, experts have no good theories as to why they were made by the extinct Diquís people who flourished on the island before the Spanish conquest

Archaeologists now believe that they are the product of the long-extinct Diquís people, who flourished on the island between 700 and 1530 AD.

However, with the arrival Spanish conquest, the true meaning of these objects was lost to time.

Speaking about the spheres in 2010, Professor John Hoopes of the University of Kansas said: ‘We really don’t know why they were made, the people who made them didn’t leave any written records.

‘The culture of the people who made them became extinct shortly after the Spanish conquest. So, there are no myths or legends or other stories that are told by the indigenous people of Costa Rica about why they made these spheres.’

Careful study shows that the objects were ground into shape, but since so many were moved from their original locations it has been extremely difficult to figure out what they could have been used for

After their discovery in the 1930s, the majority of the spheres were moved from their original locations and some were even sold as lawn ornaments.

As with so many of these mysterious objects, without their original context it is even harder for experts to understand why they might have been created.

The absence of any definitive answer and the balls’ sophisticated construction have led to some particularly imaginative speculation.

Internet theories propose that the balls’ may have been left behind by aliens or ancient super-civilisations.

Professor Hoopes adds: ‘Myths are really based on a lot of very rampant speculation about imaginary ancient civilizations or visits from extraterrestrials.’

We now know that the spheres were made by grinding roughly carved granite rocks down into smooth, polished surfaces.

However Earthly their origins, the real meaning of the Diquís Spheres is likely to remain forever unknown.